Recently I become part of the editorial team at the Bike-Sharing World Map (this is a new version, not yet launched) which is the world’s only comprehensive map of bikeshare systems, listing the approximately 2000 active systems along with another 1000 that are either in planning or already closed.

The Bike-Sharing World Map was compiled by the late Russell Meddin over the last 12 years and has recorded the gradual evolution of the capabilities of bikesharing systems, with Europe and Asian systems dominating, followed by a huge rise in American systems – but the massive change over the last four years has been the rise of dockless bikeshare systems, powered by smartphone apps, replacing the expensive fixed-docking-station systems, often publically financed and typically one-per-city. Instead, dockless is often entirely privately financed and the major operators run systems across hundreds of cities, often in direct competition with each other.

China invented the dockless concept and made it a “boom” industry by being able to manufacture the bikes very quickly – the timing was also perfect, with Chinese citizens, having previously cycled everywhere and quickly seen their cityscapes convert to the motorcar – perhaps were looking for a return to a simpler, cheaper and perhaps now quicker form of transport. There certainly was an investor boom-and-bust, with many cities being totally overwhelmed in 2017 with dockless bikes. Photos of huge, brightly coloured dockless bicycle graveyards became popular. Almost none of the systems were making money though, and the industry rapidly consolidated – a number went bust or were bought in 2018, the trigger being a snowballing of users requesting deposit refunds.

More recently still, city authorities started to address the problem and many of the larger ones have now introduced operator assessment and the awarding of quotas of bike numbers based on this. This means that, on the assumption that operators obey the quota directives and also maintain the largest fleets they are allowed to, it is possible to calculate the approximate number of dockless bikes in each city and by extension across the world. The operators themselves don’t typically announce their fleet sizes, for commercial reasons, and generally don’t provide public APIs either, so this is typically the most effective way to understand the numbers. The authorities don’t always publish these quotas either, but China’s local press often conducts investigations into and their local journalists are occasionally allowed access into city operations centres where sharing bicycle fleets – amongst other transport assets, are monitored.

This graphic, from a QQ article, shows a screen in such a centre in Chengdu, on which are live statistics for dockless bikeshare – one of my Chinese-speaking colleagues at UCL translated it and this is the source that Bike-Sharing World Map is using for Chengdu:

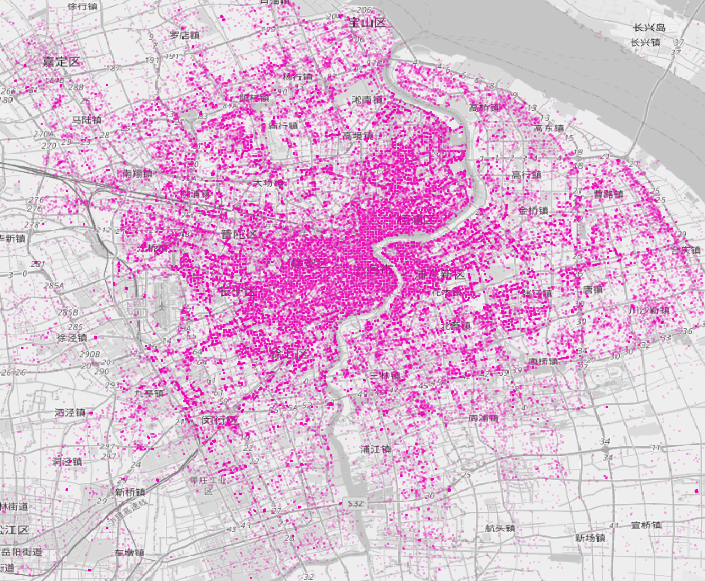

It is possible to mine Mobike’s undocumented API for bike locations, although at the centre of the densest cities, even this exhaustive approach will miss many of the bikes. Here is a map showing a snapshot of 152,300 Mobike bikes available for rent – around 1/3rd of the estimated ~500,000 strong fleet in Shanghai, earlier this month (N.B. quirks with the China datum mean the locations don’t match perfectly with the underlying OpenStreetMap map):

Beijing’s totals peaked in September 2017 with 2.35 million dockless bikes. In 2018 a quota of 1.91 million bikes was introduced, more recently authorities have reduced this to 900,000. The Chinese “big 3” as of 2020 are all in the capital city – Mobike (morphing into Meituan Bikes having been bought by them), Hellobike (bought by Youon, the biggest operator of docked public systems in China) and Didi’s Qingju brand (Didi is China’s Uber, it bought the assets from Bluegogo when they went bust). There is also a residual ofo presence – the app remains live and there are bikes rentable though it – although they have been largely unmanaged for a while now, the company having been embroiled in a deposit refunds scandal.

Beijing is behind just Chengdu, and possibly Shanghai, in terms of total numbers of bikes.

The industry itself continues to innovate and organise itself, with the increasing pressure from city authorities combining with the need to properly start making money. Hellobike has been one of the most nimble. It has largely avoided the investor bloat and scandals of the others by concentrating on only its home market, China, and also initially concentrating on second-tier Chinese cities, where there is less likely to be competition from Mobike/ofo/Qingju. As it has grown, it is now moving into the biggest cities and taking on all comers.

Recently, Hellobike has started to roll-out dockless hubs, which are enforced by beacons which sweep the designated areas and interact with RFID chips on the bikes. The bikes’s wheel locks will nosily unlock if a user tries to lock and end their journey outside of them. Generally, this beacon approach is much more accurate and immediate than the traditional use of GPS (or the Chinese equivalent) to enforce geofences or understand where the free bikes are for the benefit of app units and redistributors. Other organisations in China are looking at combining the extensive public CCTV camera network in many cities with China’s AI advances and machine object-detection routines, to help authorities detect which bikes are parked where and when, to help with operator scoring for future quotas.

Bike-Sharing World Map currently estimates there are 9.1 million bikeshare bikes in the world, of which at least 8.6 million (over 94%) are in China – and most of these are dockless. We are still compiling and updating the China part of the map – and the actual number could be quite a lot higher (although not as high as in mid-2017 when it was believed there were 16 million dockless bikeshare bicycles in China (10 million ofos, 5 million Mobikes & 1 million Bluegogos). The fleets may have probably halved since then, but the story of bikeshare in the world is far from complete without up-to-date numbers from China.

Terminology note: China generally refers to dockless bikeshare bicycles as “shared bicycles” or “internet bicycles” while the older dock-based systems are generally called “public bicycles” reflecting their publically owned and specified status.