Click any of the images in this article to go to the interactive map.

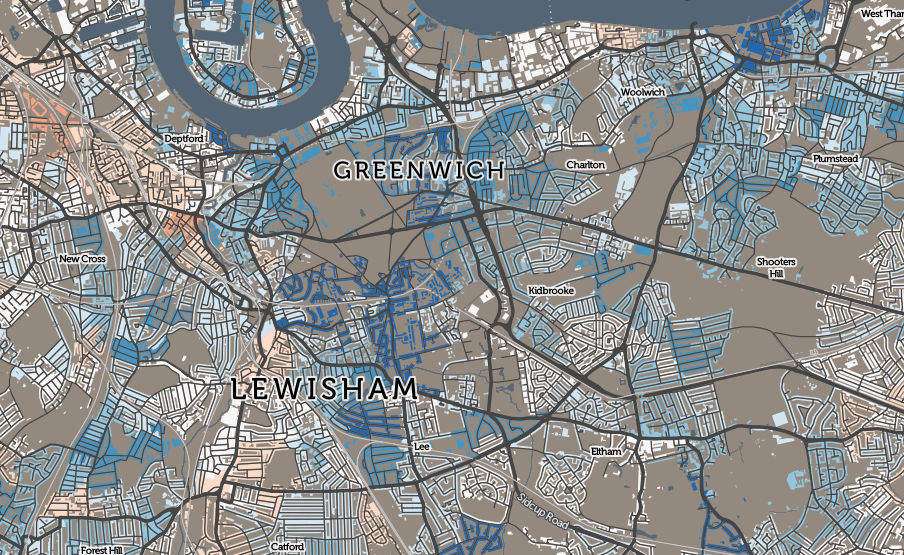

Above: A significant reduction in relative deprivation in Blackheath and Maze Hill since 2010.

I’ve just now published a number of maps on the CDRC Maps platform which uses the DataShine mapping style (more about DataShine) to show demographic data relating to consumer and other datasets.

The maps relate to the Indices of Deprivation 2015, small-area measures of deprivation in England, which were compiled and published at the end of September by OCSI on behalf of the UK Government.

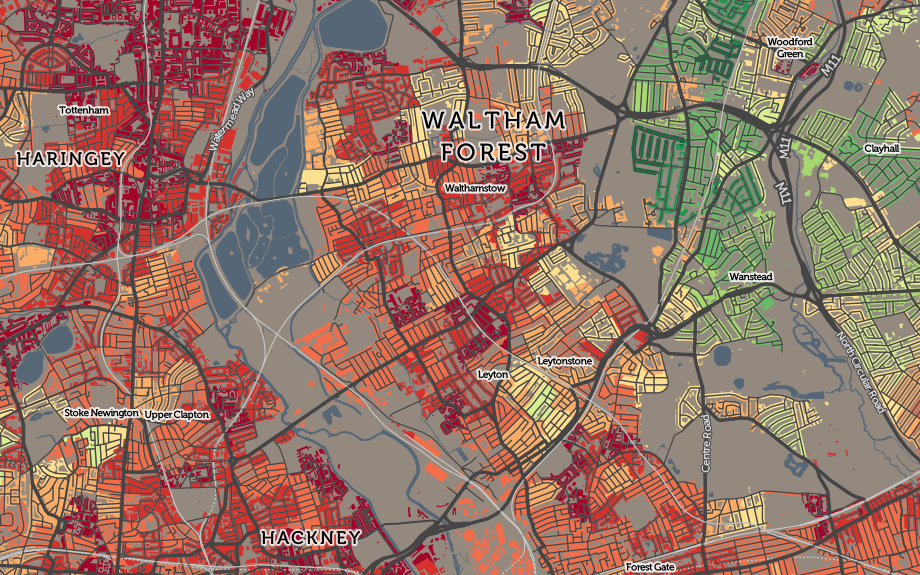

Above: Deprivation varies between Tottenham, Walthamstow and Woodford Green, in 2015.

The Indices of Deprivation (of which the Index of Multiple Deprivation, or IMD is the overall index) split England into around 32000 areas (“LSOAs”), each containing a typical population of 1500. Each area is scored for several components, which are then combined (with different weights) to produce an overall score of deprivation for the area. Note that areas with little deprivation may be mainly compared of people who are not “wealthy” but just not deprived, and therefore rank the same as areas mainly populated by extremely affluent people. IMD is a measure of deprivation, not affluence.

- Index of Multiple Deprivation 2015 (Overall rank, split by decile)

- Index of Multiple Deprivation 2010 (Overall rank, split by decile)

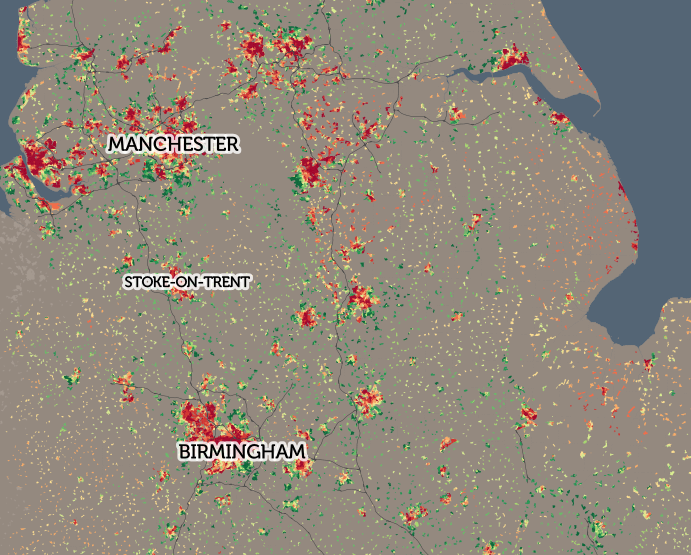

The look of these maps, with their Red-Yellow-Green colour ramp, is intentionally similar to my New Booth map of the 2010 IMD deciles which was my first “colour the houses” map and the precursor to DataShine and therefore CDRC Maps.

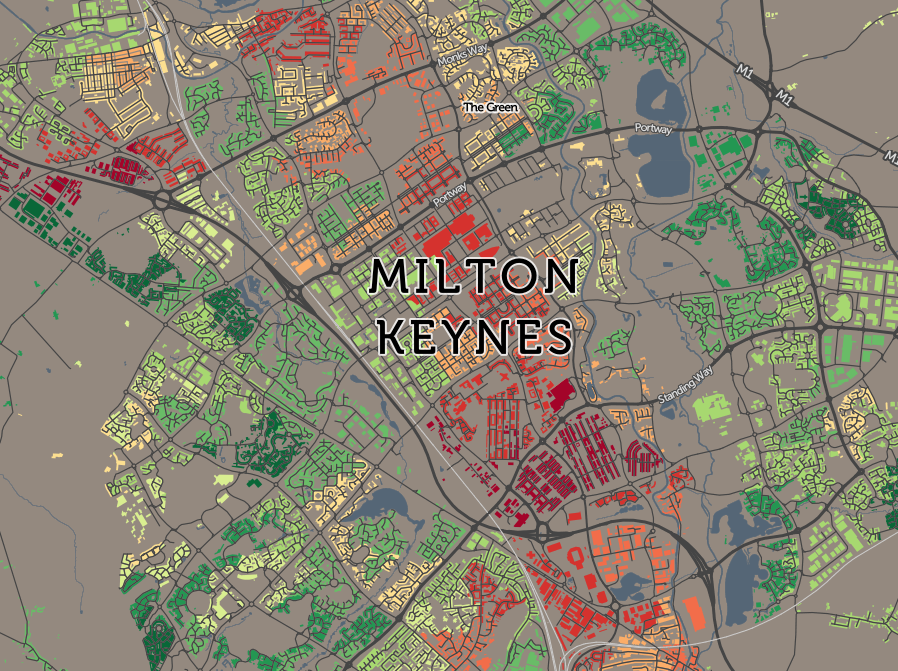

Above: Milton Keynes has a characteristic strip of high deprivation, running north/south.

These scores cannot be directly compared with those from previous exercises (2010, 2007 and 2004 are the recent ones) due to slight methodological alterations, however we can rank each area based on the overall score – this is the Index of Multiple Deprivation – and then compare ranking changes between the years. It should be noted that a decrease in rank (i.e. an increase in deprivation measure compared with other areas) does not mean that an area has become more deprived in absolute terms – it may be just becoming less deprived at a slower rate. I have mapped the overall rank change from 2010 to 2015, and also the rank change of the component which measures the effects of crime on deprivation, as this shows some particularly interesting spatial characteristics.

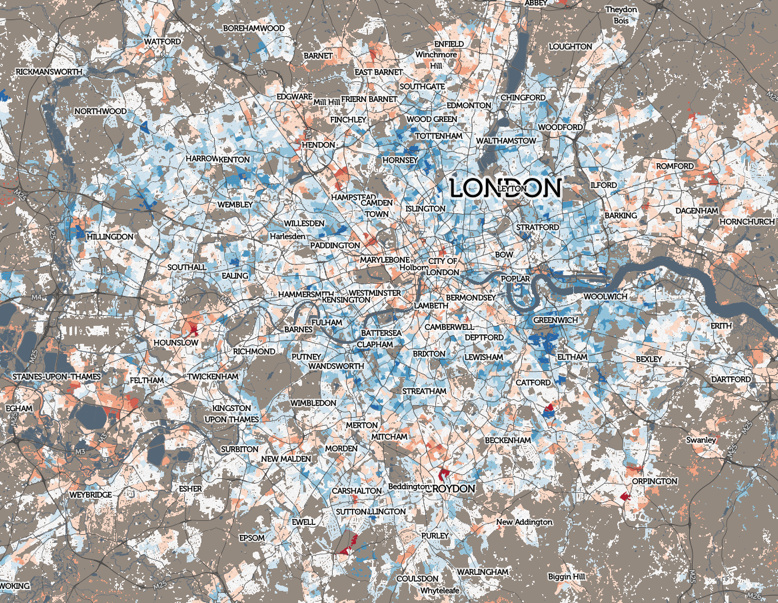

Looking at the overall changes, London’s pattern is striking:

Above: London has an inner-city “ring” of blue showing a large reduction in relative deprivation since 2010.

London’s inner city areas – Zones 2-4 – have becoming significantly less deprived in the last year. Indeed London, in general, has done very well recently relative to the rest of England, with only a few areas (St John’s Wood, Thornton Heath, Mill Hill, East Barnet and Hounslow) showing a significant increase in relative deprivation levels. Again, this may mean that they are still becoming less deprived, just at a slower rate. By comparison, Blackheath, Ealing, Upton, North Wembley and Crouch End have become dramatically less deprived since 2010. There are smaller pockets throughout the city who are are also showing marked moves in both directions – see the interactive map. I use a different (Red-White-Blue) colour ramp for these maps, to emphasise that they are showing changes.

- Change in Overall rank for IMD from 2010 to 2015 (Split by equal rank divergence)

- Change in Crime rank for IMD from 2010 to 2015 (Split by equal rank divergence)

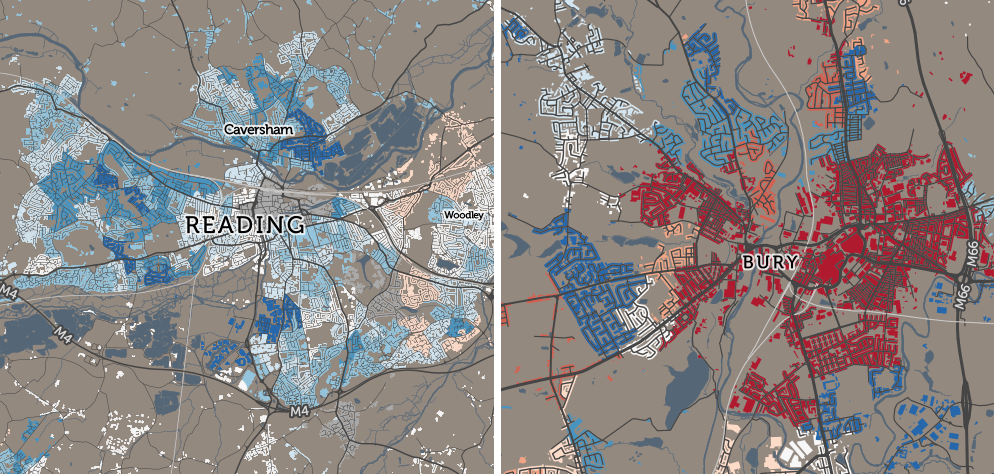

Above: The contribution of crime to deprivation has significantly dropped in Reading and increased in Bury.

Some of the more notable results for changes in the crime component ranking of the IMD are in Reading (where the impact of crime on deprivation has significantly reduced) and Bury (where it has had a significantly greater impact). In both towns (see above, presented at different scales) however, other components have acted in the opposite direction, such as the deprivation ranking of these two places, with respect to the rest of England, has not significantly changed in five years. Bury, was, and still is, already significantly more deprived than Reading, the difference between the two has increased.

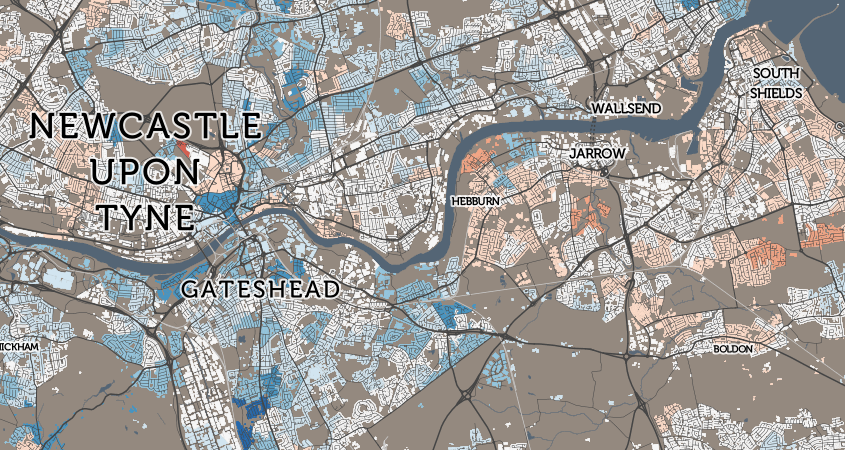

Another example: comparing Gateshead with nearby South Shields. The former coming up, the latter going down:

Gateshead is almost universally moving out of deprivation at a faster rate than the rest of England, while South Shields is change much more slowly.

The components are income, employment, education, health, crime, barriers to housing and services, and living environment. Their weights are summarised in this nice infographic from gov.uk.

There is also an official summary which maps the data slightly differently. One of its analyses – Chart 6 – shows the local authorities (LA) where relative deprivation has significantly fallen, by measuring the proportion of areas within the LA that have moved out of the bottom 10% in the IMD, between 2010 and 2015. The top four are: Hackney, Tower Hamlets, Greenwich and Newham. These are four of the five Olympic Boroughs. The fifth, Waltham Forest, is also in the top 10. East London is changing.

See these maps and various geodemographic classifications at CDRC Maps.

Across middle England, cities are more deprived than the countryside, with notable exceptions (such as Shrewsbury, Cambridge, northern Leeds and western Sheffield).