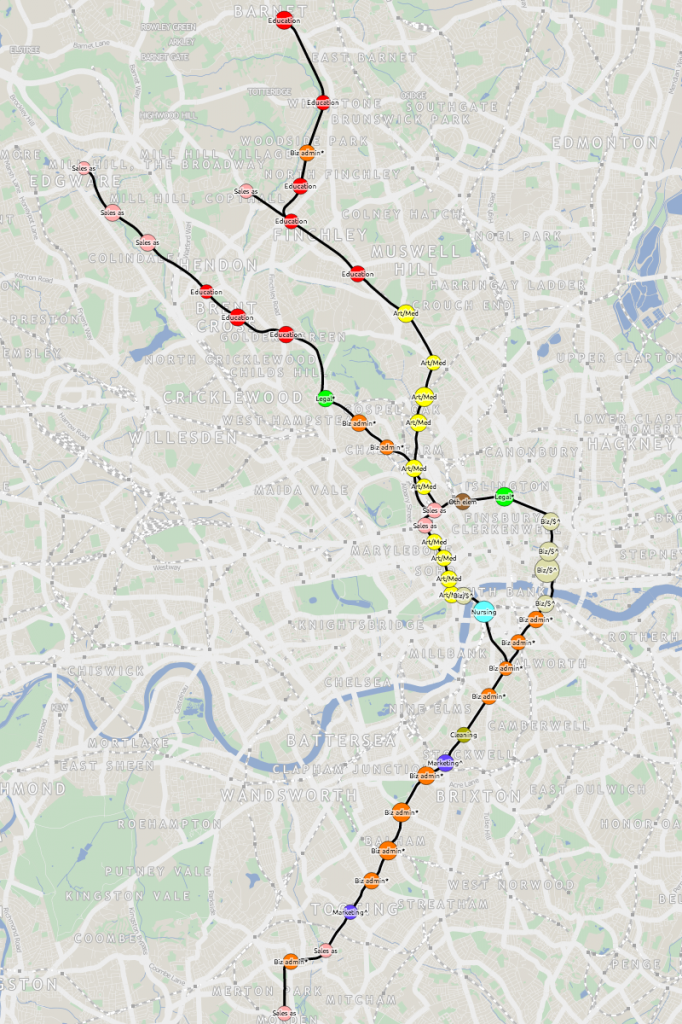

I’ve extended my map of tube journeys and busy stations (previous article here) to add in an interesting metric from the 2011 census – that of the second most commonly spoken language (after English) that people who live nearby speak. To do this I’ve analysed all “output areas” which wholly or partly lie within 200m radius of the tube station centroid, and looked at the census aggregate data for the metric – which was a new one, added for the most recent census.

See the new map here.

Also available as an A2 print.

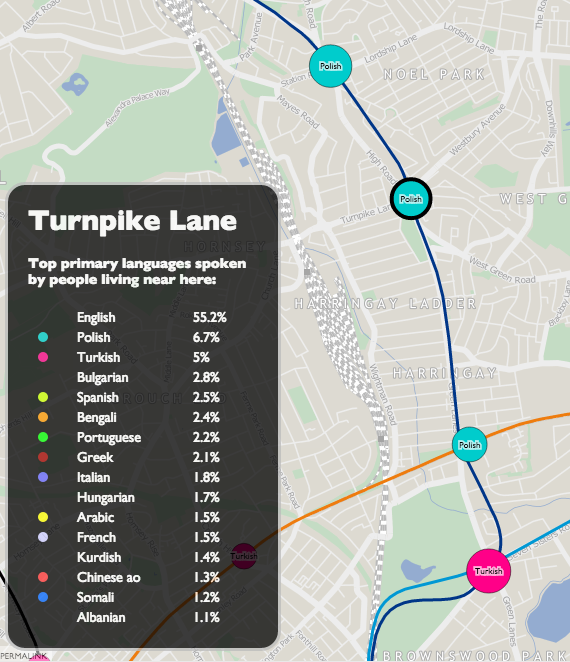

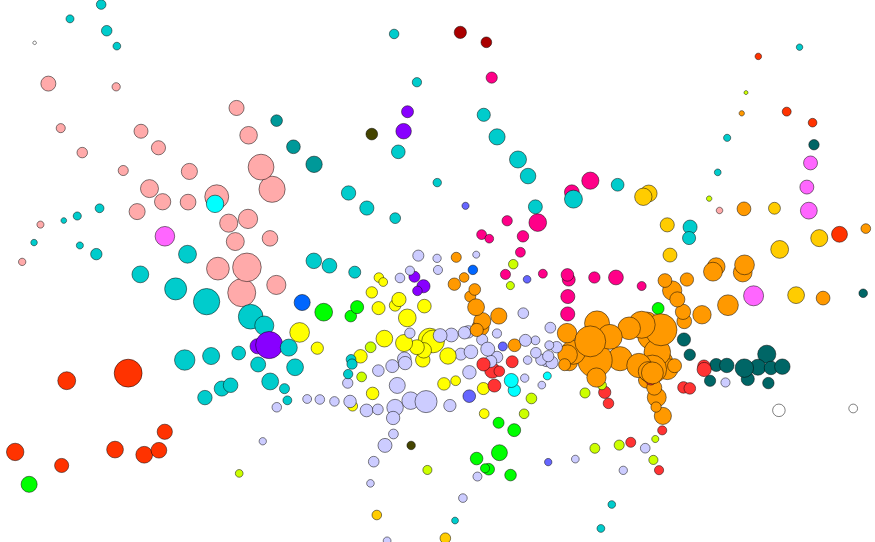

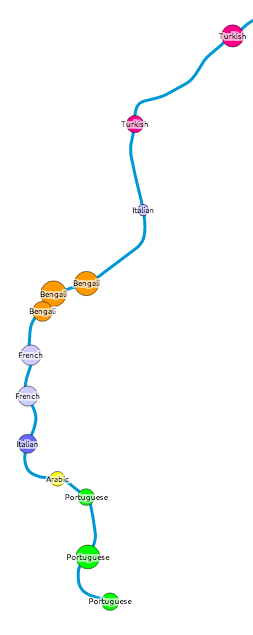

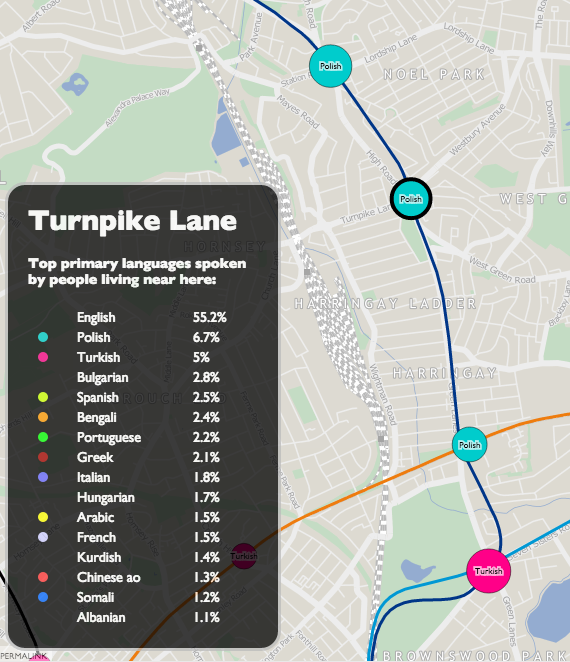

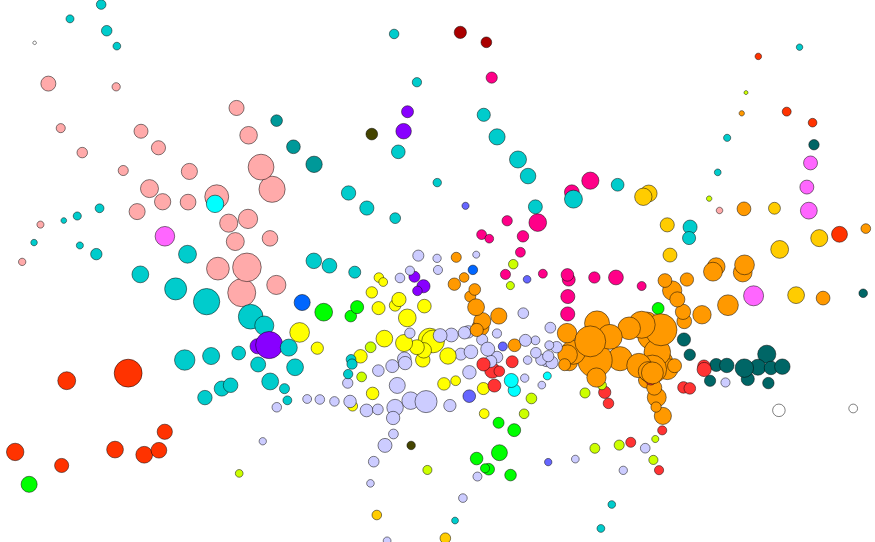

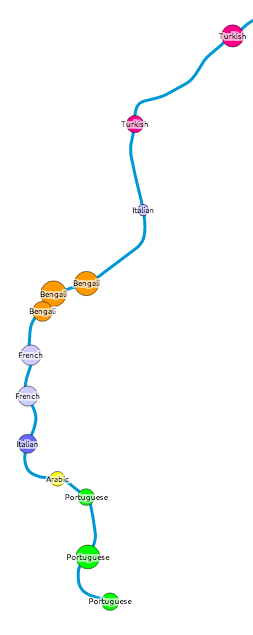

Each tube station has a circle coloured by, after English, the language most spoken by locals. The area of the circle is proportional to the percentage that speak this language – so a circle where 10% of local people primarily speak French will be larger (and a different colour) than a circle where 5% of people primarily speak Spanish.

Each tube station has a circle coloured by, after English, the language most spoken by locals. The area of the circle is proportional to the percentage that speak this language – so a circle where 10% of local people primarily speak French will be larger (and a different colour) than a circle where 5% of people primarily speak Spanish.

Language correlates well with some ethnicities (e.g. South Asian) but not others (e.g. African), in London. So some familiar patterns appear – e.g. a popular, and uniform, second language appearing at almost all Tower Hamlets stations. Remember, the map is showing language, not origin – so many of the “Portuguese” speakers, for instance, may be of Brazilian origin.

Click on each station name to see the other languages spoken locally – where at least 1% of local speakers registered them in the census. There is a minimum of 10 people to minimise small number “noise” for tube stations in commercial/industrial areas. In some very mono-linguistic areas of London (typically in Zone 6 and beyond the GLA limits) this means there are no significant second languages, so I’ve included just the second one and no more, even where it is below 1% and/or 10 people.

This measure reveals the most linguistically diverse tube station to be Turnpike Lane on the Piccadilly Line in north-east London, which has 16 languages spoken by more than 1% of the population there, closely followed by Pudding Mill Lane with 15 (though this area has a low population so the confidence is lower). By contrast, almost 98% of people living near Theydon Bois, on the Central Line, speak English as their primary language. English is the most commonly spoken language at every tube station, although at five stations – Southall, Alperton, Wembley Central, Upton Park and East Ham – the proportion is below 50%.

A revealing map, and I will be looking at some other census aggregate tables to see if others lend themselves well to being visualised in this way.

I’ve also included DLR, Overground, Tramlink, Cable Car and the forthcoming Crossrail stations on the map. Crossrail may not be coming until 2018 but it’s very much making its mark on London, with various large station excavations around the capital.

The idea/methodology is similar to that used by Dr Cheshire for Lives on the Line. The metric was first highlighted by an interesting map, Second Languages, created by Neal Hudson. The map Twitter Tongues also gave me the idea of colour coding dots by language.

One quirk is that speakers of Chinese languages regularly appear on the map at many stations, but show as “Chinese ao” (all other) rather than Cantonese, whereas actually in practice, the Chinese community do mainly speak Cantonese (Yue) in London. This is likely a quirk of the way the question was asked and/or the aggregate data compiled. Chinese ao appears as a small percentage right across London, perhaps due to the traditional desire for Chinese restaurant owners to disperse well to serve the whole capital? [Update – See the comments below for an alternative viewpoint.]

The TfL lines (underground, DLR etc), station locations and names all come from OpenStreetMap data. I’ve put the collated, tidyed and simplified data, that appears on the map, as GeoJSON files on GitHub – see tfl_lines.json and tfl_stations.json. The files are CC-By-NC, licensing information is here.

Each tube station has a circle coloured by, after English, the language most spoken by locals. The area of the circle is proportional to the percentage that speak this language – so a circle where 10% of local people primarily speak French will be larger (and a different colour) than a circle where 5% of people primarily speak Spanish.

Each tube station has a circle coloured by, after English, the language most spoken by locals. The area of the circle is proportional to the percentage that speak this language – so a circle where 10% of local people primarily speak French will be larger (and a different colour) than a circle where 5% of people primarily speak Spanish.