(From my research blog)

OpenStreetMap, the free wiki world map, is starting to come of age. The project is now six years old, and is gradually becoming noticed in wider circles, with AOL and Mapquest producing their own versions of the map, support from Google and Microsoft, and an ecosystem of companies set up around commercialising the data. Perhaps the highest profile the project has had recently was when, in the days following Haiti’s huge earthquake in January 2010, the country was swiftly mapped remotely in high-detail by contributors from around the world, becoming a useful tool for disaster relief teams. Meanwhile, the project itself continues to expand, with the availability of high-resolution Microsoft Bing imagery causing a big jump in the detail being added to the map, and new countries and areas continue to be worked on.

OpenStreetMap, the free wiki world map, is starting to come of age. The project is now six years old, and is gradually becoming noticed in wider circles, with AOL and Mapquest producing their own versions of the map, support from Google and Microsoft, and an ecosystem of companies set up around commercialising the data. Perhaps the highest profile the project has had recently was when, in the days following Haiti’s huge earthquake in January 2010, the country was swiftly mapped remotely in high-detail by contributors from around the world, becoming a useful tool for disaster relief teams. Meanwhile, the project itself continues to expand, with the availability of high-resolution Microsoft Bing imagery causing a big jump in the detail being added to the map, and new countries and areas continue to be worked on.

A couple of OpenStreetMap guides became available just before Christmas, and I have one of them – OpenStreetMap: Using and Enhancing the Free Map of the World . It’s published by UIT Cambridge and available on Amazon. The authors are Frederick Ramm, Jochen Topf and Steve Chilton. The book is in its first English edition – Ramm/Topf wrote the previous German editions of the book, while Steve Chilton has translated the work and updated with the latest developments. The authors are a real authority – Ramm/Topf are well known in the German OpenStreetMap community, running a company Geofabrik which builds on OSM, while Steve Chilton is a professional cartographer who has designed and maintained the “standard” OpenStreetMap map you see at http://osm.org/.

. It’s published by UIT Cambridge and available on Amazon. The authors are Frederick Ramm, Jochen Topf and Steve Chilton. The book is in its first English edition – Ramm/Topf wrote the previous German editions of the book, while Steve Chilton has translated the work and updated with the latest developments. The authors are a real authority – Ramm/Topf are well known in the German OpenStreetMap community, running a company Geofabrik which builds on OSM, while Steve Chilton is a professional cartographer who has designed and maintained the “standard” OpenStreetMap map you see at http://osm.org/.

The book has a dual purpose – to act as both a guide for using and getting the most out of OpenStreetMap data, and contributing to it. It runs to over 300 pages and is split into four sections. The first section is an introduction, it outlines the basic structure of the project and the community behind OpenStreetMap. This is followed by the longest section in the book, which details how to contribute to the project, from wandering around your local street to using one of the available editors. It includes a detailed guide to Potlatch, the online editor which many people will use when starting out with contributing to the project. It also introduces several other editors, which is good in terms of balance, although new users do not necessarily need to learn more than one.

The book has a dual purpose – to act as both a guide for using and getting the most out of OpenStreetMap data, and contributing to it. It runs to over 300 pages and is split into four sections. The first section is an introduction, it outlines the basic structure of the project and the community behind OpenStreetMap. This is followed by the longest section in the book, which details how to contribute to the project, from wandering around your local street to using one of the available editors. It includes a detailed guide to Potlatch, the online editor which many people will use when starting out with contributing to the project. It also introduces several other editors, which is good in terms of balance, although new users do not necessarily need to learn more than one.

The third section is about taking OpenStreetMap data and creating maps from it. Examples of cartographical style sheets are included and carefully dissected. There is some code here, but it is well annotated so shouldn’t prove too intimidating to read. Finally, for the most advanced users, the fourth chapter details getting down under the hood of the OpenStreetMap architecture and “hacking” the data, including documenting the API calls to OpenStreetMap servers to programmatically get and put information.

One of the most interesting parts of the book is actually one of the appendices, detailing country-specific quirks of the project. One of OpenStreetMap’s greatest strengths is that it is a map and spatial database of the whole world – but individual countries have different available data sources, “tagging” customs for features, and community structures, and the appendix makes for insightful reading. Being a UK contributor of a British-founded project, I find it can be easy to overlook regional differences, so it’s good to understand why some countries have mapping features in a certain way.

I found the book extremely comprehensive. I have been a long-time contributor to the project and have used the data in numerous ways, but I was surprised to learn several new details from the book, such as how to set up banned-turn indicators, and a clear discussion of the licensing.

The book is perhaps most valuable over and above other project resources because it has a consistent editing style and level of detail. The “traditional” way of learning OpenStreetMap has been through the online wiki, but this is prone to varying levels of accuracy and detail depending on the enthusiasm of the authors – so having a single-style book like this is a considerable help in fully appreciating a very diverse project. I did feel that the section on contributing is slightly longer than it needs to be – choosing just one of the editors, such as Potlatch, rather than going into multiple editors in detail, many of which duplicate functionality, would have helped shorten this section. As, I think, people are more likely to read this book to understand how to use the project’s data and resources, rather than become advanced contributors, I would imagine many readers will end up skipping over the whole section. I did also think a history of the project would have been a nice inclusion.

Books on fast changing internet projects such as OpenStreetMap are prone to go out of date quickly. With this in mind, the authors have created a special website, http://www.openstreetmap.info/ which will contain updates to the book as the project continues to evolve. As the English edition has just been published, the book itself however is bang up to date and so stands as a definitive reference.

The website also has a PDF version of one of the chapters in the second section, Mapping Practice. You can also download a copy of the country-specific appendix.

The book succeeds in simultaneously being OpenStreetMap for Dummies, OpenStreetMap: The Missing Manual and the O’Reilly OpenStreetMap book – that is to say, complete beginners, intermediate users and enthusiasts/hackers will all get something out of the book. If you are at all interested in the OpenStreetMap project, even if you don’t intend to contribute to the project but are just curious about what it is or what you can do with it, then I recommend this book. It’s as near-perfect as any book can be about one of the web’s, and the geospatial community’s, most exciting projects. More details on Amazon.

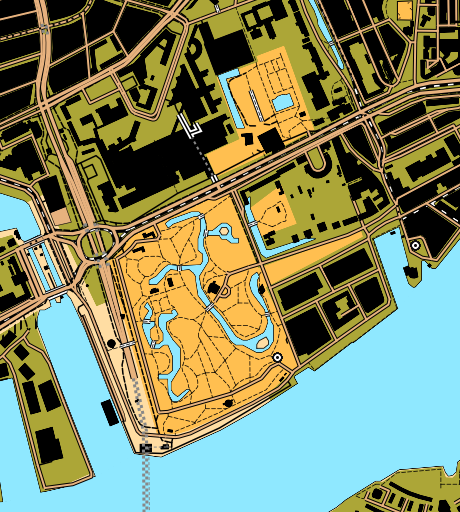

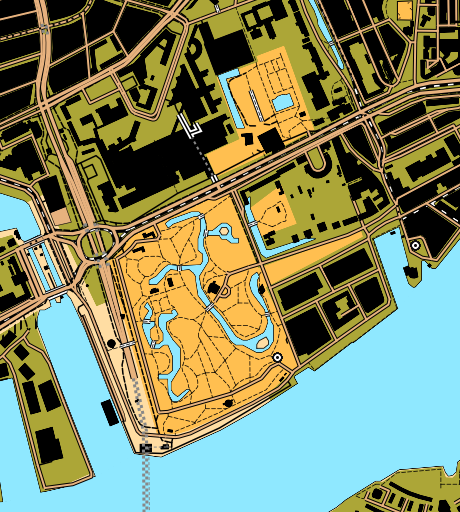

The photo of the author Steve Chilton is by Chris Fleming. Below is an example of custom cartography using OpenStreetMap, for OpenOrienteringMap, CC-By-SA OpenStreetMap and contributors.

The book has a dual purpose – to act as both a guide for using and getting the most out of OpenStreetMap data, and contributing to it. It runs to over 300 pages and is split into four sections. The first section is an introduction, it outlines the basic structure of the project and the community behind OpenStreetMap. This is followed by the longest section in the book, which details how to contribute to the project, from wandering around your local street to using one of the available editors. It includes a detailed guide to Potlatch, the online editor which many people will use when starting out with contributing to the project. It also introduces several other editors, which is good in terms of balance, although new users do not necessarily need to learn more than one.

The book has a dual purpose – to act as both a guide for using and getting the most out of OpenStreetMap data, and contributing to it. It runs to over 300 pages and is split into four sections. The first section is an introduction, it outlines the basic structure of the project and the community behind OpenStreetMap. This is followed by the longest section in the book, which details how to contribute to the project, from wandering around your local street to using one of the available editors. It includes a detailed guide to Potlatch, the online editor which many people will use when starting out with contributing to the project. It also introduces several other editors, which is good in terms of balance, although new users do not necessarily need to learn more than one.

The book has a dual purpose – to act as both a guide for using and getting the most out of OpenStreetMap data, and contributing to it. It runs to over 300 pages and is split into four sections. The first section is an introduction, it outlines the basic structure of the project and the community behind OpenStreetMap. This is followed by the longest section in the book, which details how to contribute to the project, from wandering around your local street to using one of the available editors. It includes a detailed guide to Potlatch, the online editor which many people will use when starting out with contributing to the project. It also introduces several other editors, which is good in terms of balance, although new users do not necessarily need to learn more than one.

The book has a dual purpose – to act as both a guide for using and getting the most out of OpenStreetMap data, and contributing to it. It runs to over 300 pages and is split into four sections. The first section is an introduction, it outlines the basic structure of the project and the community behind OpenStreetMap. This is followed by the longest section in the book, which details how to contribute to the project, from wandering around your local street to using one of the available editors. It includes a detailed guide to Potlatch, the online editor which many people will use when starting out with contributing to the project. It also introduces several other editors, which is good in terms of balance, although new users do not necessarily need to learn more than one.