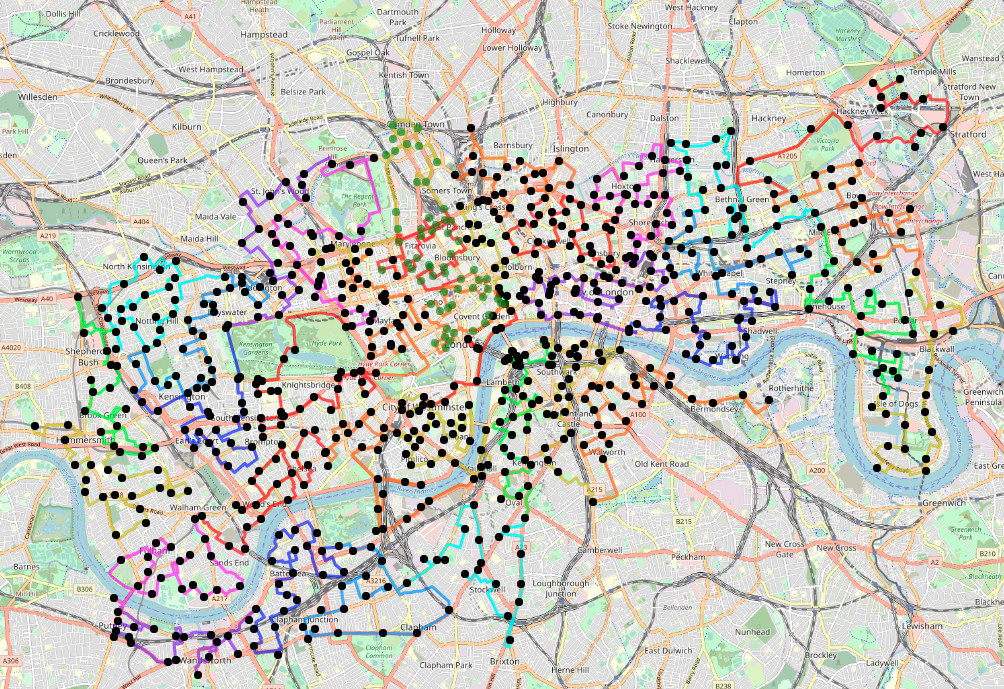

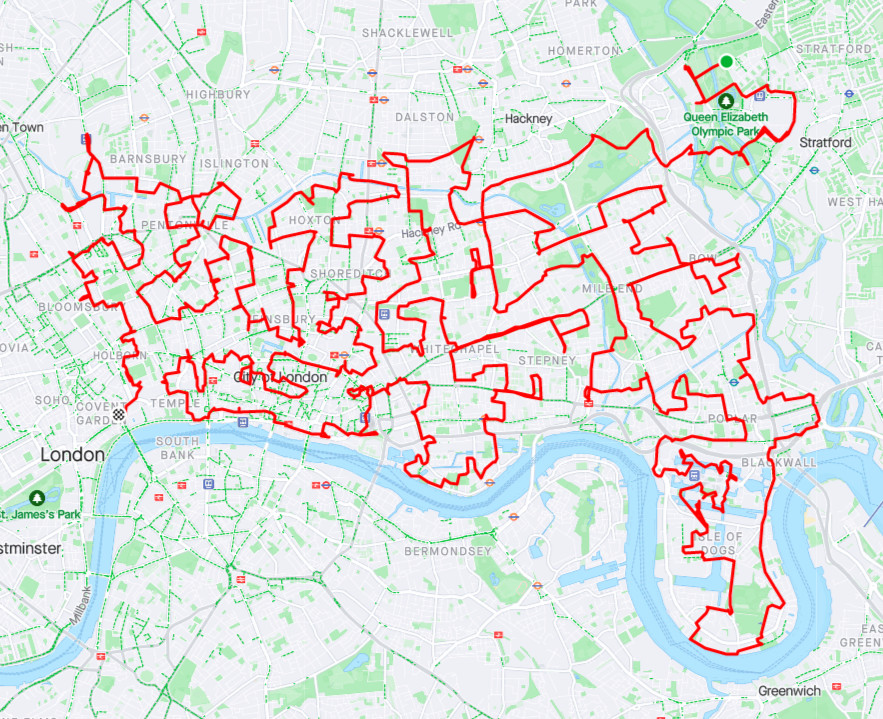

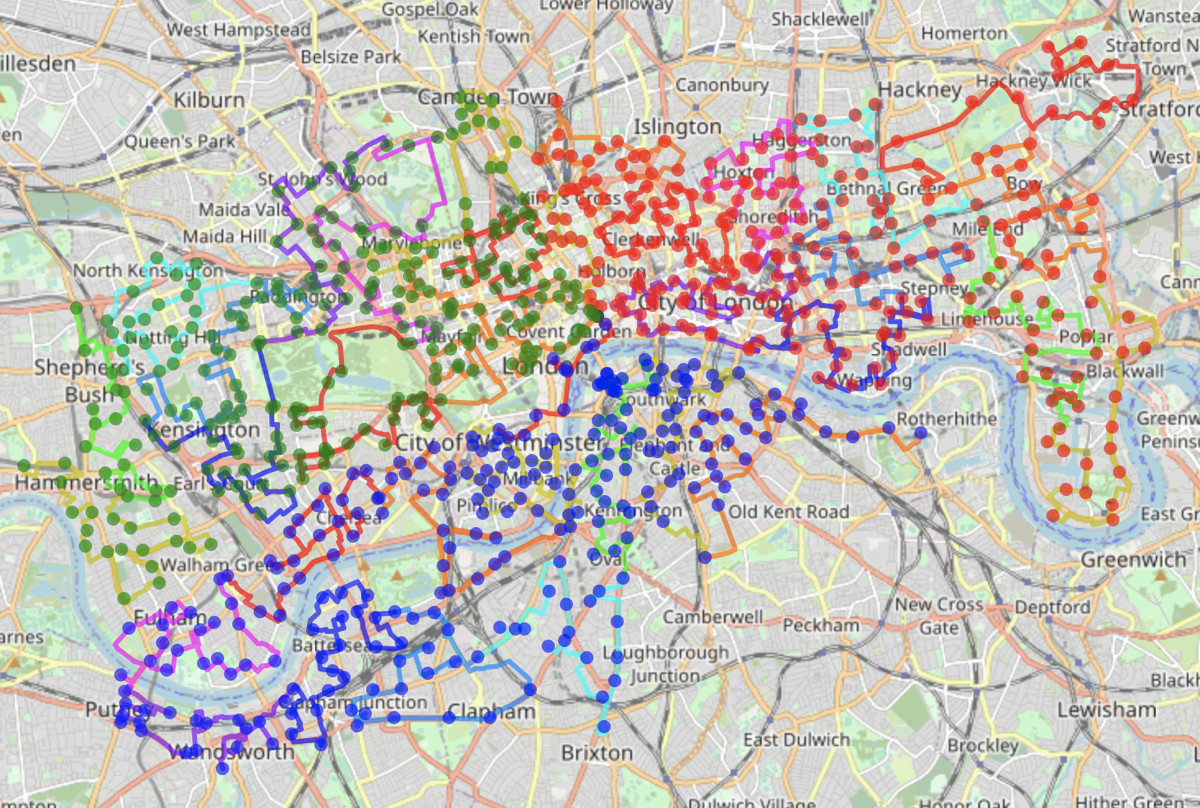

Yes, we did it again. All the Docks 2 took place in London on 9 July. Five teams (up from three last time) each cycled between a fifth of the Santander Cycles docking stations in London. I again did the routes, splitting up the ~800 docking stations into 5 routes of 160 docking stations apiece. To make it more of a challenge, this time we started in central London, at the same docking station we were all to finish at, with the teams looping out from central, before returning.

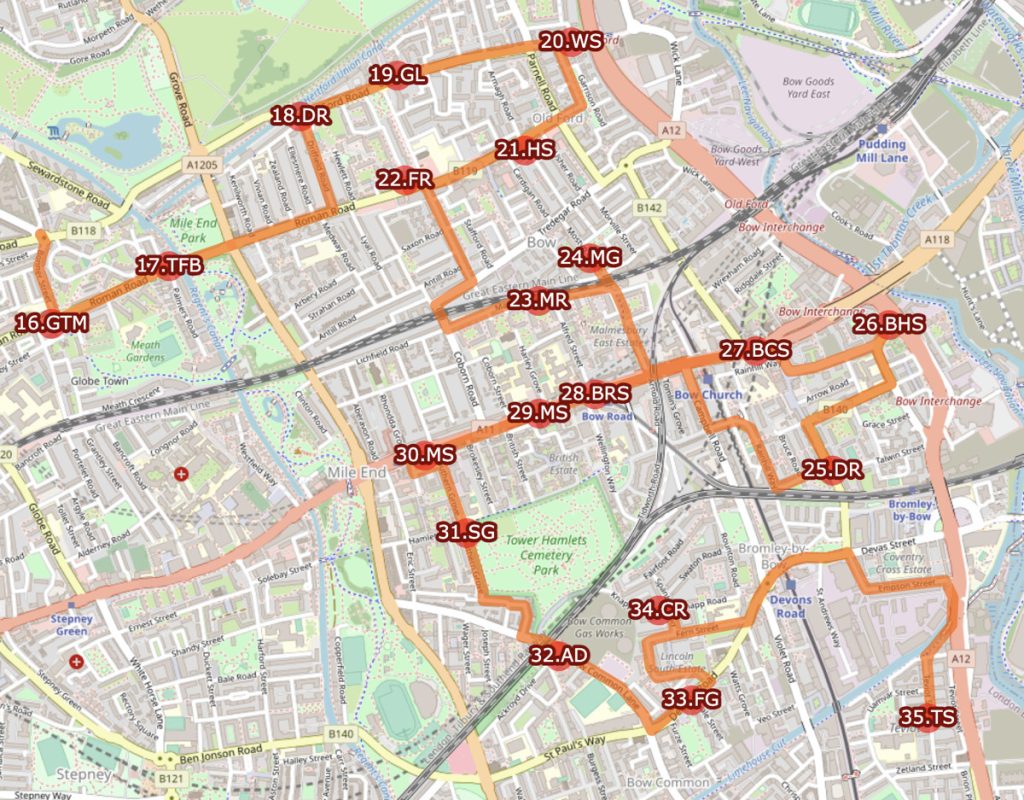

Each team was to visit exactly the same number of docking stations, with routes measured at around 71.7km +/- 1km maximum, to make it a genuine equal challenge.

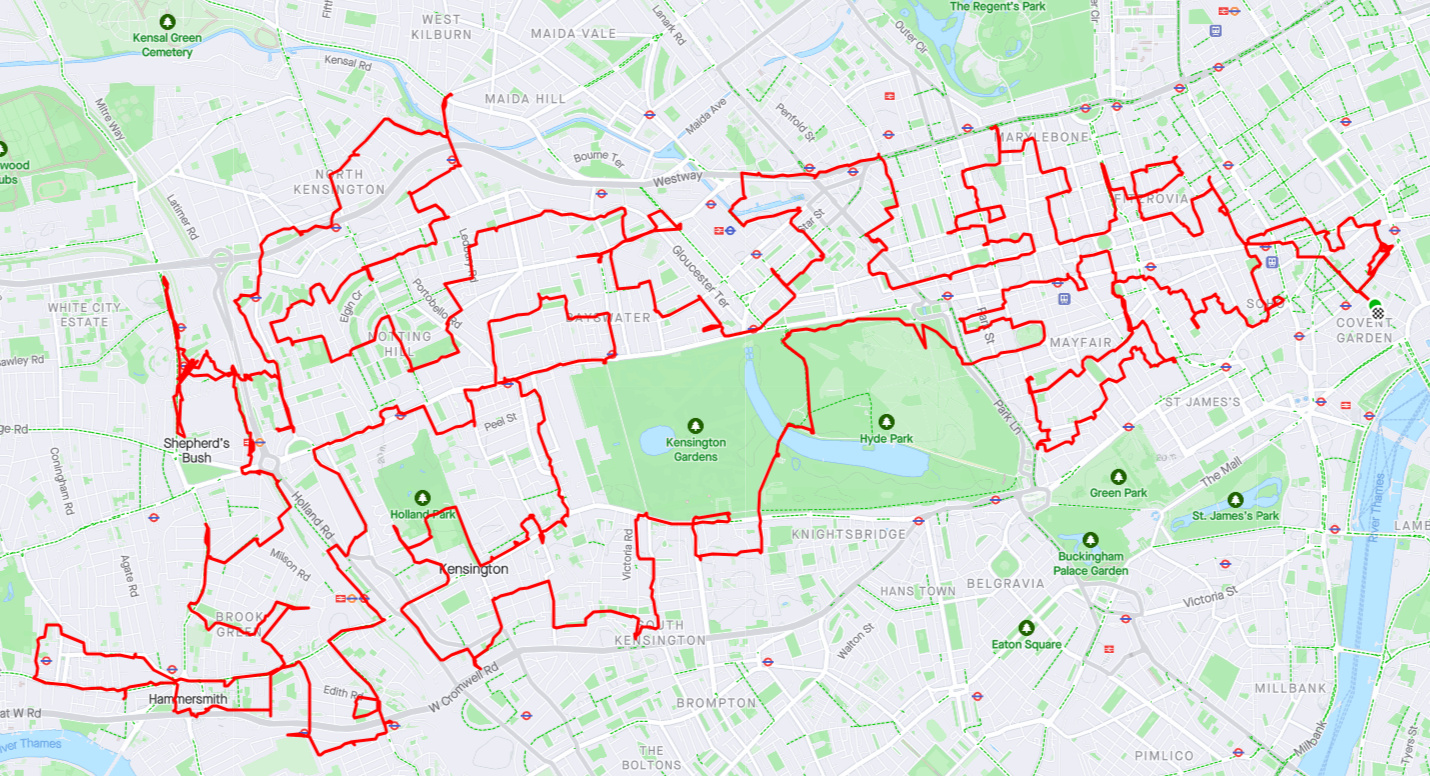

I was on Team West this time, with Westfield London and Hyde Park being the highlights, contrasting from the Olympic Park and Canary Wharf last time round. Team West was an all-UCL team.

(Route courtesy of West Team lead rider Dr James Todd)

What went right?

Nearly everything this time.

All teams started and finished. Four of the five teams finished within 5 minutes of each other, which I think is great after nearly 8 hours of cycling. One team finished half an hour quicker than the others, and therefore won, but then they did skip stopping for lunch. Fair play to them.

The weather was good, and Sunday traffic was light so the challenge was more pleasant.

TfL didn’t open any extra docking stations during the day, so no on-the-fly replanning was needed.

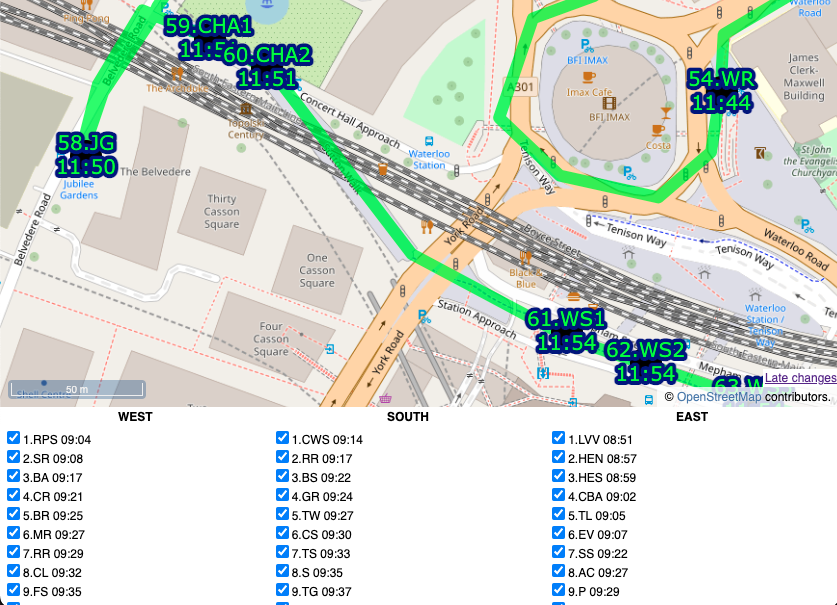

All teams used my online map to record their docks so we got a nearly complete dataset (albeit with a few errors in it) showing the teams docking.

The challenge had an official website this time, courtesy of overall coordinator Stephen Bee.

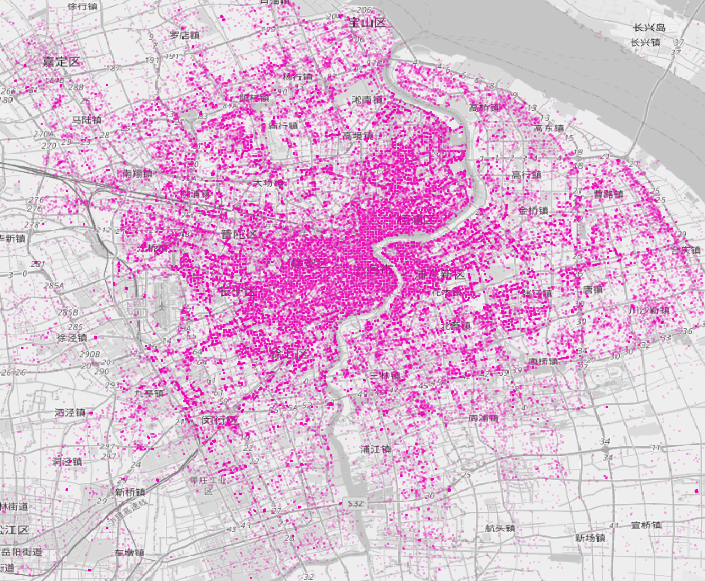

Prof Wood at City used the live API to generate some really nice live visuals of the progress, which he later turned into an animation:

The routes seemed to work OK – there were some quirks, such as the nearly 2 mile cycle North Team had across South Hackney to get to the Olympic Park. Originally, this area was Team East, but adding this in to the Team North route was essential to balance the lengths of the different routes. For Team West, we only had a couple of no-entry signs that I hadn’t anticipated and the odd road closure due to building work. Team South and Team Putney both had to cross the Thames four times.

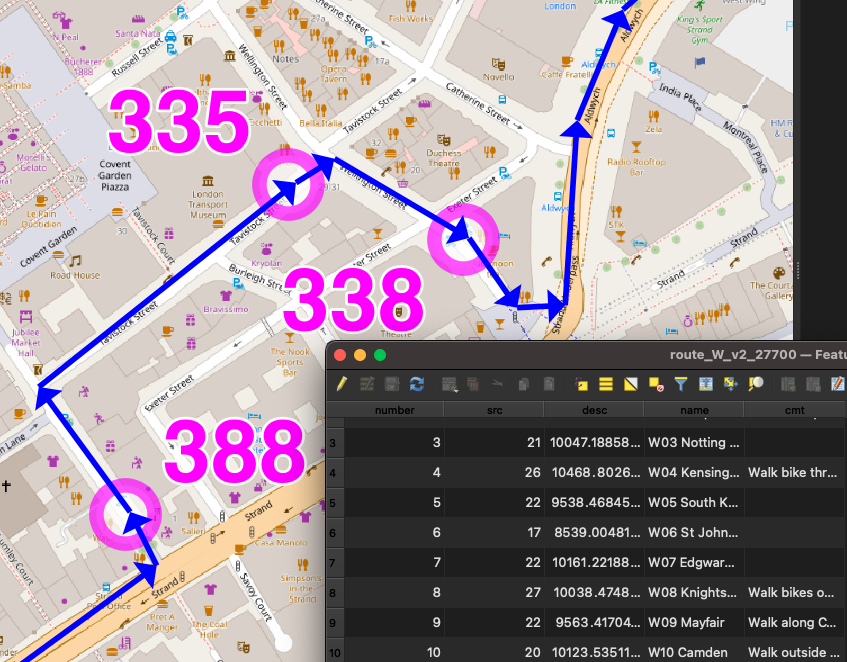

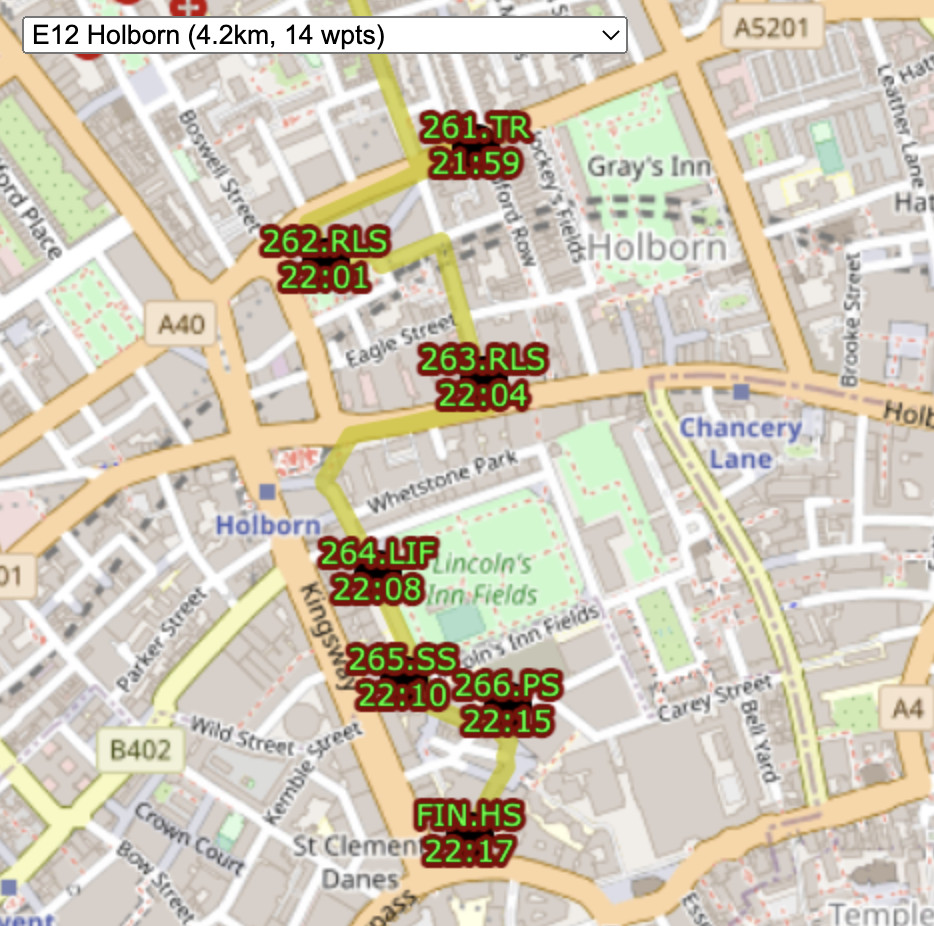

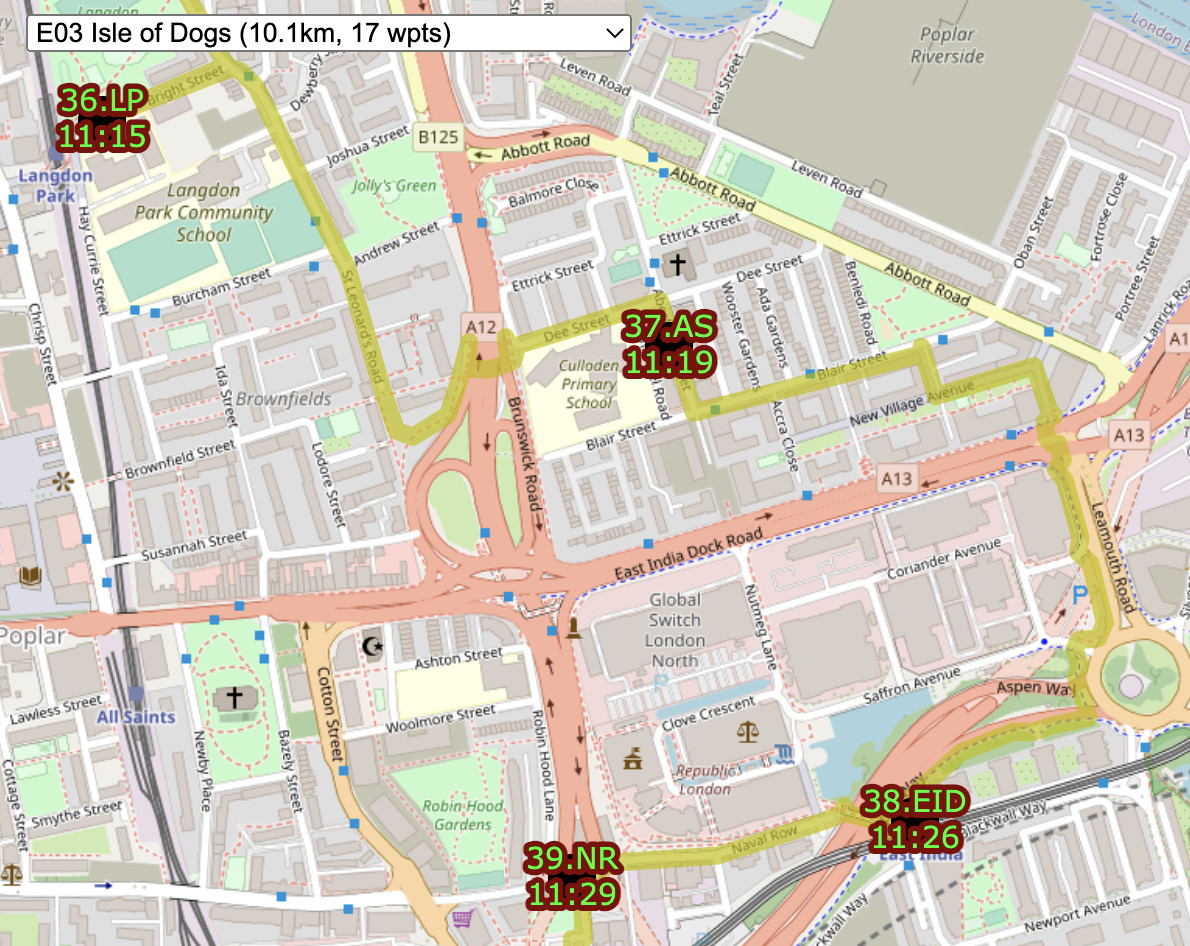

This time I put each stage (stages are approximately 10km or 1 hour of cycling, so each team had 7 stages) through a TSP solver – I wrote some Python code to make appropriate calls to an OSRM server (routing.openstreetmap.de) and modify the results to create a GeoJSON, viewed in QGIS. Unfortunately, the pre-defined vehicle profiles available on the server meant that the cycling routes avoided trunk roads, whereas in London they are generally fine to go on, and also the router was too enthusiastic about using pavements for quite long sections, and even steps (a no-no for the 25kg Santander Cycles bikes). Next time, I would run my own OSRM server, with a a custom defined profile more suitable for London cycling. But the routes generated did suggest some optimisations and I was able to reduce the route lengths by around 1%, in places substantially rerouting sections. So, a win overall for using TSP engines.

Everyone seemed to enjoy themselves and the ~4:30pm finish was ideal for a couple of pints outside at the pub opposite.

What went wrong?

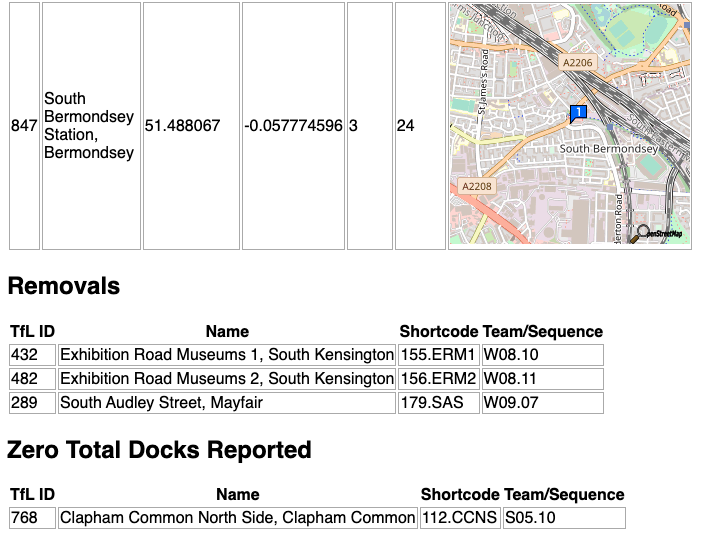

The biggest problem was the London 10K. This was happening almost unbeknown to us, except that I luckily realised it was happening and going to be a problem, when I read a TfL summary of events happening, the night before. The impact was quite major on the start of the event – I suspected that TfL would, unannounced, turn off a number of docking stations, but worse, the route was blocking the first stage for two of the teams – Team Putney and Team West started right down the race route. Urgent replanning the night before was needed. Team Putney did a dramatic diversion out via Waterloo and Lambeth Bridge (taking on some Team South docking stations). In compensation, Team South picked up some of Team Putney’s docking stations at the end of the day. Team West’s route would also be blocked at Regent Street. In the end, a diversion around Oxford Street, and a bit of replanning to add in a loop, didn’t lengthen the route too much. In the end, 5 docking stations were indeed turned off, they came back online in the mid-afternoon, just before the teams closed in on them, so all’s well that ends well. Probably, Team Putney could have sneaked down the race route, as the race started at 0930 and we started at 9am – and the course wasn’t completely sealed off until the runners started.

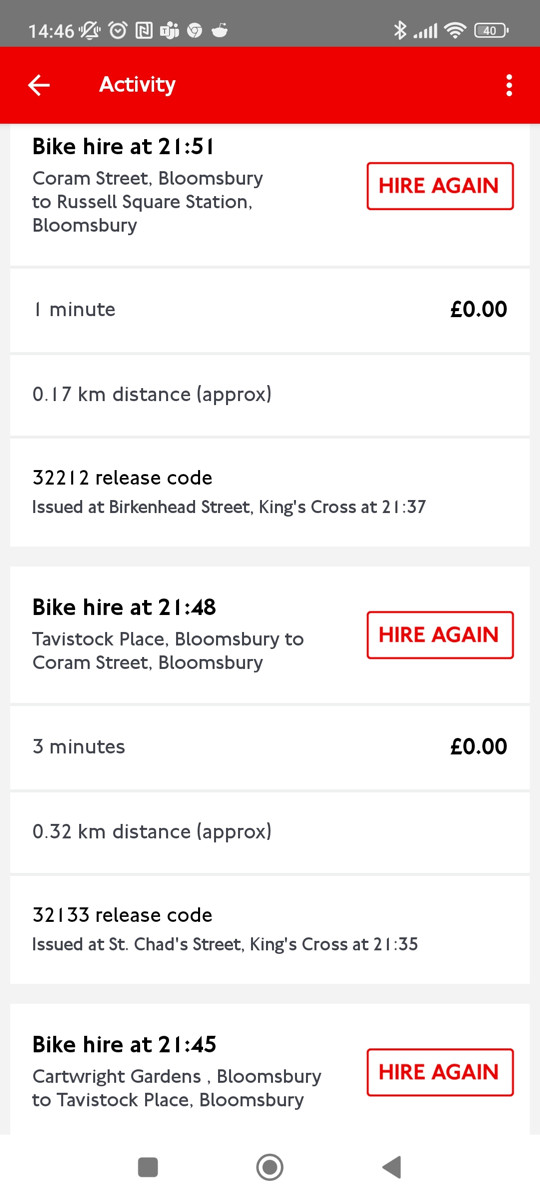

My team (Team West) suffered a couple of technical problems due to docks going offline. This meant that the bikes docked, but journeys did not “end” in the Santander Cycles system. Therefore, a new journey could not be started. These issues were solved with phone call to the helpdesk, however, the first time, the operator made us jog back to the previous docking station (as we had already cycled on with another bike/account) to confirm cycle numbers to prove we were there. Very annoying and we lost 15 minutes this way. TfL should know when their docking stations are offline. When it happened near the end, we again had to jog back, and used the remaining key for the last two hops. In the end, it didn’t deny us the win – we’d already lost that by having too leisurely a lunch. (Two accounts are necessary for the challenge, to avoid a 30 second account timeout between successive hires).

There were again some problems with the team version of my live map. The API response went quite slow during the day, even though I had tested it to work within a few milliseconds. This meant it was easy to tick, and then accidentally untick while waiting for the response to come back. Future UX tweaks would mean a confirmation needed to untick, or to tick a station later than the next one in the list.

Routes generally worked well but Team West was surprised by the sudden removal of the cycle track on the inner side of the Hammersmith Gyratory, necessitating a diversion and then some hairy lane swerves to get back on track. Sudden ending of otherwise good cycle infrastructure is a long-standing London quirk. Looking at maps, even now, I still can’t work out how cyclists are supposed to get from Talgarth Road (north side) to King Street. Maybe via Shortlands? But then why have such a great cycle path on Talgarth Road itself?

I need to automate the process of creating the routes and the files generated from the routes, particularly going from the GeoJSONs in QGIS, to the GPX route/waypoint files and the dock list. Like last time, I went through four iterations of the routes, each correction and publishing cycle took 2-3 hours.

Late changes, mainly relating to the London 10K replanning but also the need to get five route with the same number of docking stations and essentially the same length, meant I couldn’t include some “iconic” London cycling pieces in the routes – namely the Kensington Gardens Broad Walk, Parliament Square, or Battersea Bridge.

Team leads were given Go-Pros to wear, which were set to do time-lapse imagery, but these soon ran out of batteries. A different kind of device might be needed for this kind of thing.

We were expecting more on-the-day involvement from TfL (both technical and promotional) and some other data organisations as the event was part of London Data Week, indeed this set the event date. In the end, apart from Prof Wood’s excellent contribution above, we were on our own. It is possible some further outputs may appear.

Some final notes

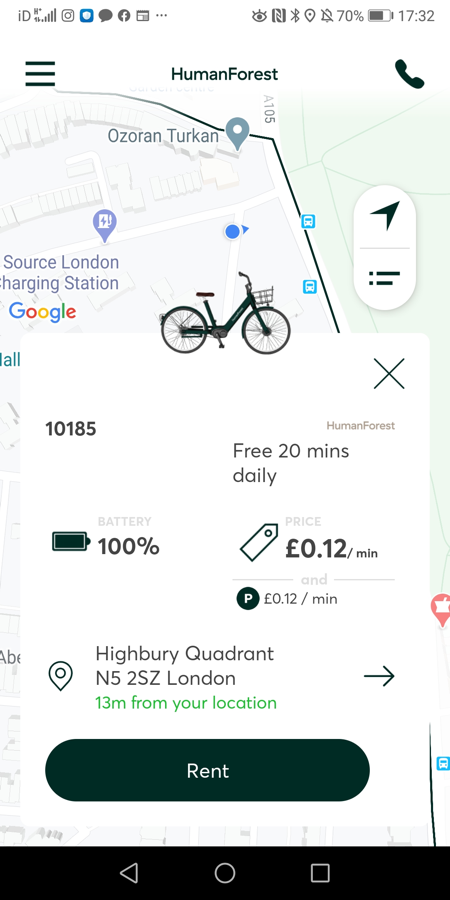

All teams used at least one Santander Cycle between each dock, docking and undocking each time, to make the challenge official. There were no rules on what bikes the other members could be on, so one person had the great idea of doing ~55 minute rentals on the Santander Cycle electric bikes, each time. This is great because it makes the challenge more enjoyable, having an electric boost. It also will have only cost an extra ~£8 or so (as the surcharge for electric is £1 for up to an hour). The only drawback is no easy way to mount your phone on a hire bike. But i think I would be happy to trade that for an easier pedal.

Until next time…