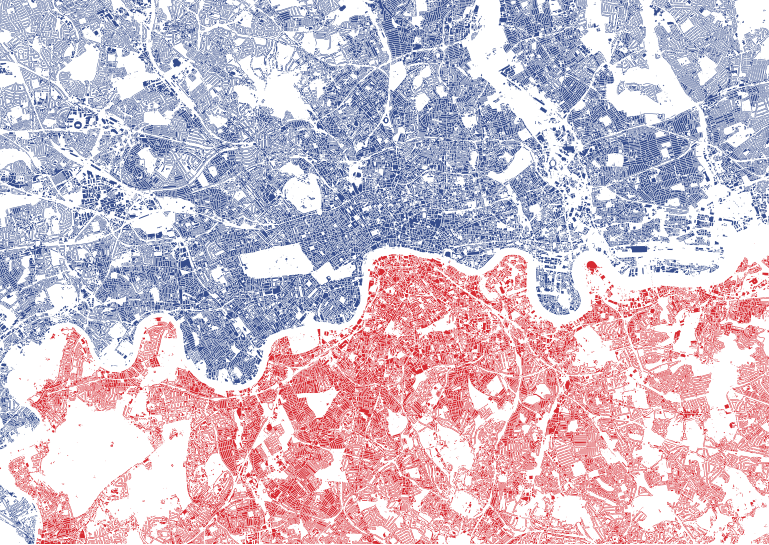

The above interactive map compares the popularity of different CitiBike docking stations in New York City, based on the number of journeys that start/end at each dock. The top 100 busiest ones are shown in red, with the top 20 emphasised with pins. Similarly, the 100/20 least popular ones are shown in blue*.

CitiBike is a major bikesharing system that launched in New York City earlier in the summer and has been pulling in an impressive number of rides in its first few weeks – it regularly beats London’s equivalent, whose technology it shares, in terms of daily trip counts, even though London’s system is almost twice as big (compare NYC).

Different areas have different peak times

Here are three maps showing the differences in the popularity of each docking station at different times of the day: left covers the “rush hour” periods (7-10am and 4-7pm), the middle is interpeak (10am-4pm), the domain of tourists, and on the right is evening/night (7pm-7am) – bar-goers going home? The sequence of maps show how the activity of each docking station varies throughout the day, not how popular each docking station is in comparison to the others.

Red pins = very popular, red = significantly more popular than average, green = significantly less popular than average. Binning values are different for each map. Google Maps is being used here. See the larger version.

Some clear patterns above – with the east Brooklyn docks being mainly used in the evenings and overnight, the rush hours highlighting major working areas of Manhattan – Wall Street and Midtown, and interpeak showing a popular “core” running down the middle of Manhattan.

The maps are an output from the stats created by a couple of requests for CitiBike data came through recently – from the New York Times and Business Insider – so it was a good opportunity to get around to something I had been meaning to do for a while – see if I can iterate through the docking station bike count data, spot fluctuations, and infer the number of journeys starting and ending at each docking station.

I was able to relatively quickly put together the Python script to do this fluctuation analysis and so present the results here. I can potentially repeat this analysis for any of the 100+ cities I’m currently visualising collecting data for. Some of these cities (not New York yet) provide journey-level data in batches, which is more accurate as it’s not subject to the issues above, but tends to only appear a few months later, and only around five cities have released such data so far.

Places with persistently empty or full docks differ

Here are two maps highlighting docks that are persistently empty (left) or full (right).

Left map: green = empty <10% of the time, yellow = 10-15%, red = 15-20%, red pins = empty 20%+ of the time. Right map: green = full <2% of the time, yellow = 2-3%, red = 3-4%, red pins = empty 4%+ of the time. Google Maps is being used here. Live version of full map, live version of empty map.

The area near Central Park seems to often end up with empty docking stations, caused perhaps by tourists starting their journeys here, going around Central Park and then downtown. Conversely, Alphabet City, a residential (and not at all touristy) area fairly often has full docking stations – plenty of the bikes for the residents to use to get to work, although not ideal if you are the last one home on a bike.

How the stats were assembled and mapped

As mentioned above, I assembled the stats by looking at the data collected every two minutes, iterating it, and counting changes detected as docking or undocking “events”, while also counting the number of spaces or bikes remaining for the second set of maps.

There are a couple of big flaws to this technique – firstly, if a bike is returned and hired within a single two minute interval (i.e. between measurements) then neither event will be detected, as the total number of bikes in that docking station will have remained constant. This problem mainly affects the busiest docks, and those that see the most variation in incoming/outgoing flows, i.e. near parks and other popular tourist sites. The other issue is that redistribution activities (typically trucks taking bikes from A to B, ideal from full docks to empty docks) are not distinguishable. In large systems, like New York’s, this activity is however a very small proportion of the total activity – maybe less than 5%, and so generally discountable in a rough analysis like this. I detected 1.6 million “events” which equates to 0.8 million journeys which each have a start and end event. The official website is reporting 1.1 million journeys during the same period, suggesting that this technique is able to detect around 64% of journeys.

I’ve used Google Fusion Tables to show the results. Although its “Map” function is somewhat limited, it is dead easy to use – just upload a CSV of results, select the lat/lon columns, create a map, and then set the field to display and which value bins correspond to which pin types. Just a couple of minutes from CSV to interactive map. There are a few other similar efforts out there – which aim to take point-based data and stick it quickly on a map, but Google’s Fusion Tables does the job and is easy to remember.

The data is one month’s worth of journeys – 17 July to 16 August. One note about the popularity map – the data. I am really just scratching at the surface with what can be done with the data. One obvious next step is to break out weekend and weekday activity. There are a few other analysis projects around – this website is analysing the data as it comes in, to an impressive level of detail.

* Any docks added in the last month will probably show as being unpopular at the moment, as it’s an absolute count over the last month, regardless of whether the dock was there or not.

Over the last couple of days,

Over the last couple of days,