London has a new bikeshare system – and it’s appeared by surprise, overnight. oBike is a dockless bikeshare. The company is based in Singapore, where it runs a number of large dockless systems there and in various Chinese cities, Melbourne, Amsterdam and Zurich, it is also likely coming to Washington DC in the USA and to Berlin in Germany, based on some recent job postings.

And now they’ve shipped 29 lorry-loads of nearly 5000 bicycles to London, the number being revealed in a now-deleted tweet by a logistics company:

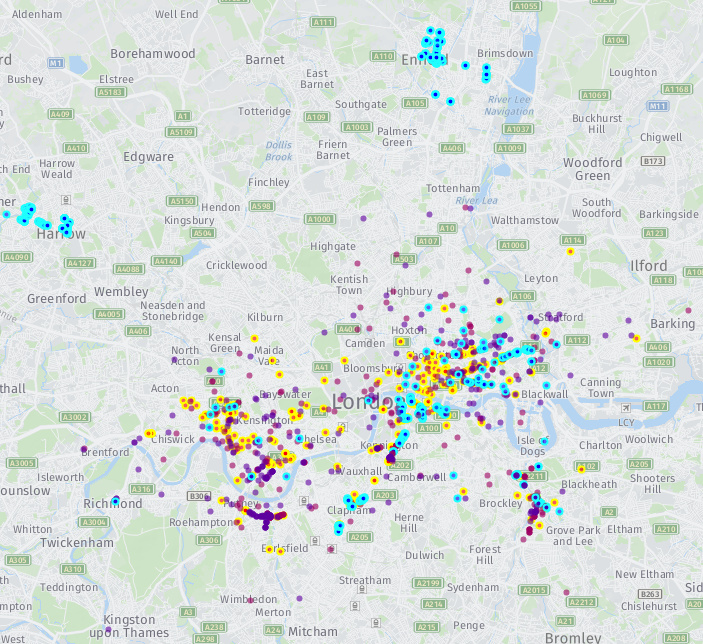

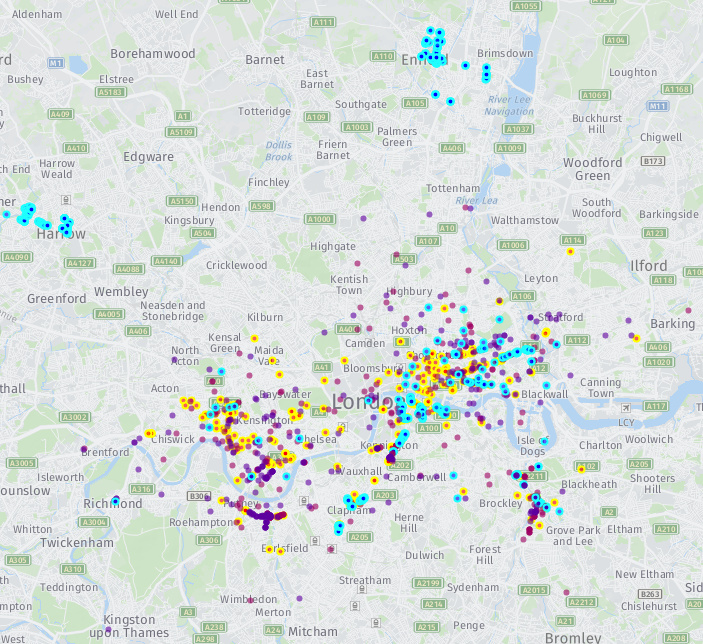

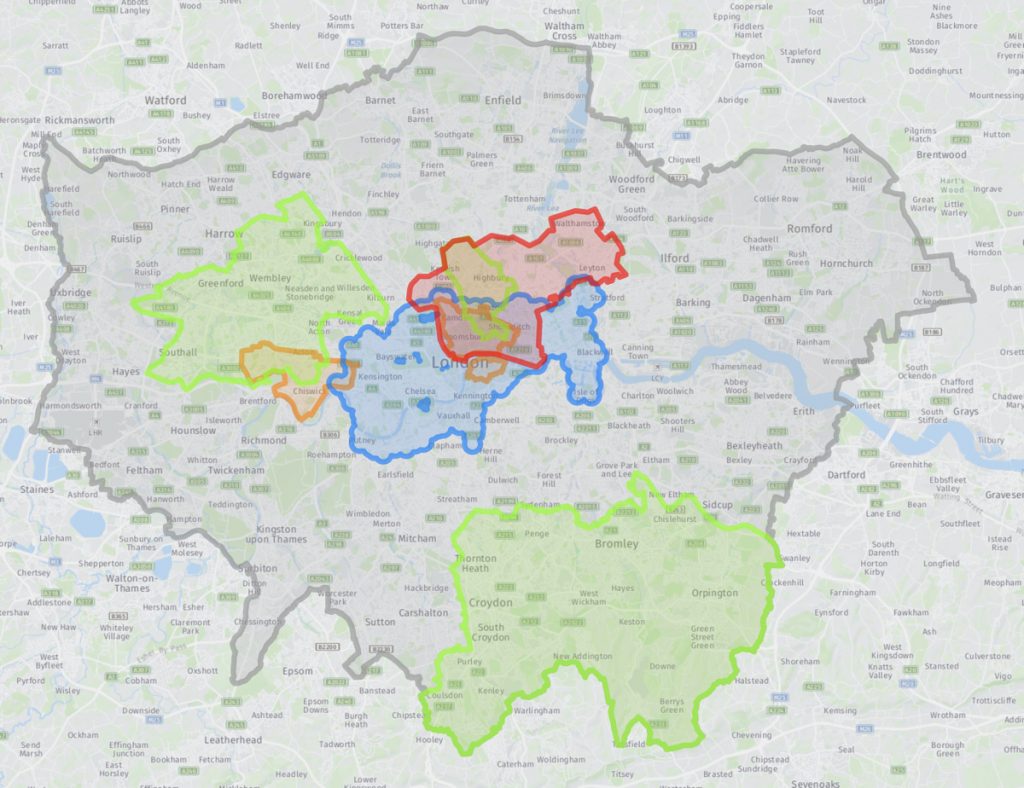

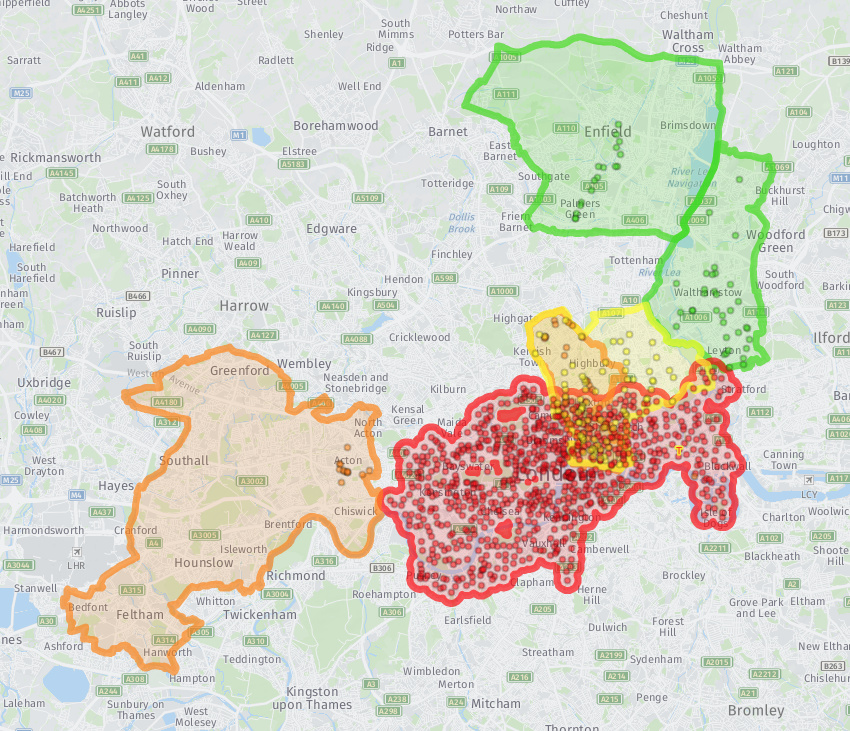

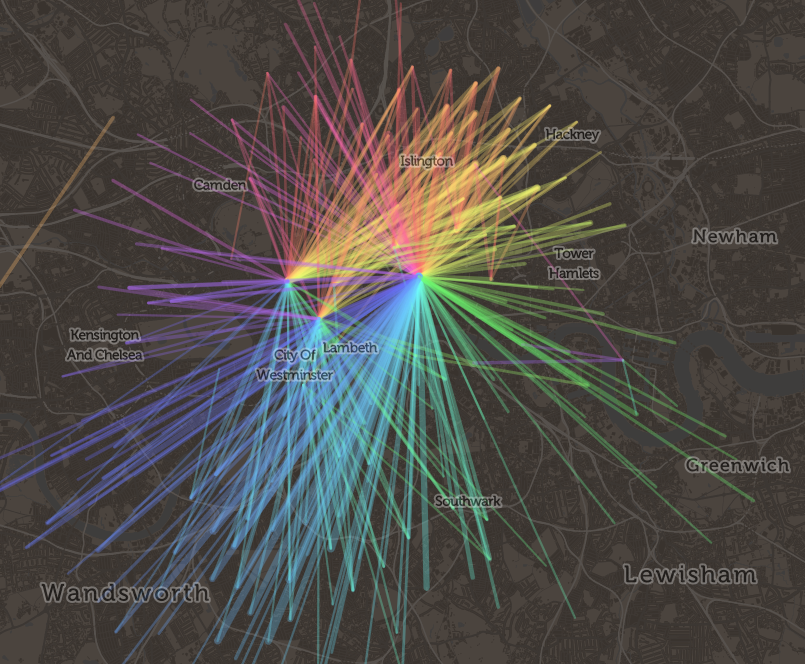

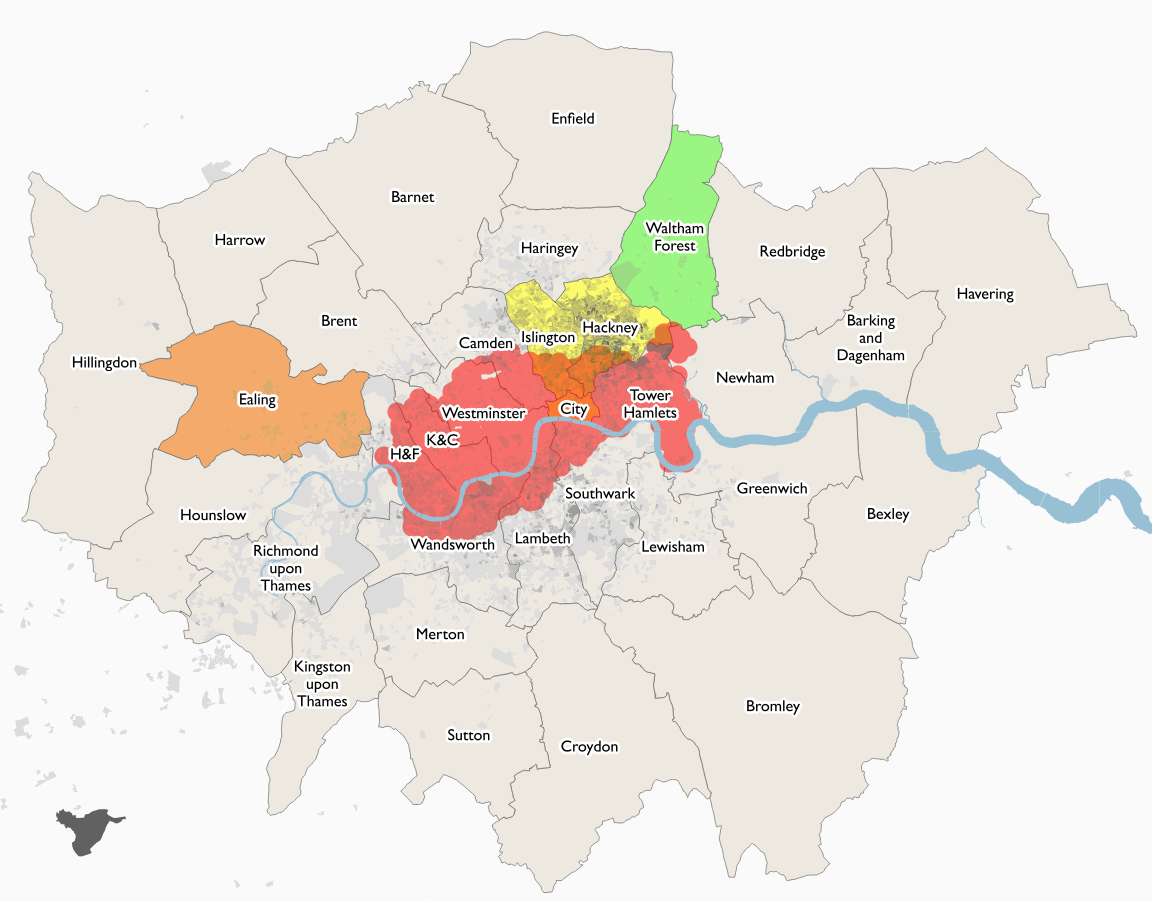

Just under 1500 have been released so far, initially being “seeded” in groups along the major roads in Tower Hamlets and Hammersmith & Fulham boroughs (400 in each), and more recently in Wandworth, Clapham, Kennington, Lewisham, Waterloo, Harrow* and Enfield*, with “organic” use moving the bikes out as far south as Kingston, and as far east as East Ham (plus possibly in the river near Erith…) There have been several hundred journeys already, with the great majority of bikes having been moved at least once from their initial deployment.

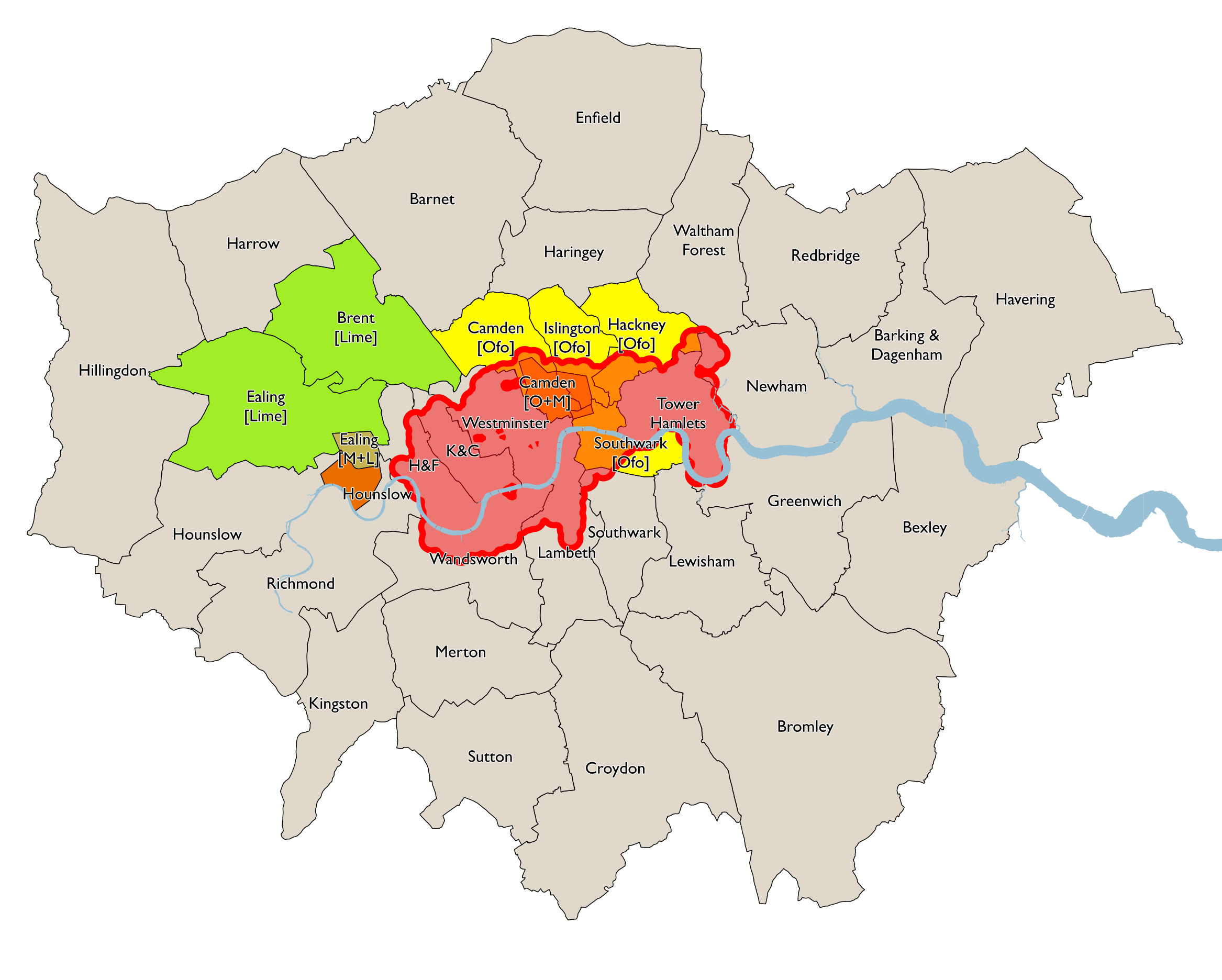

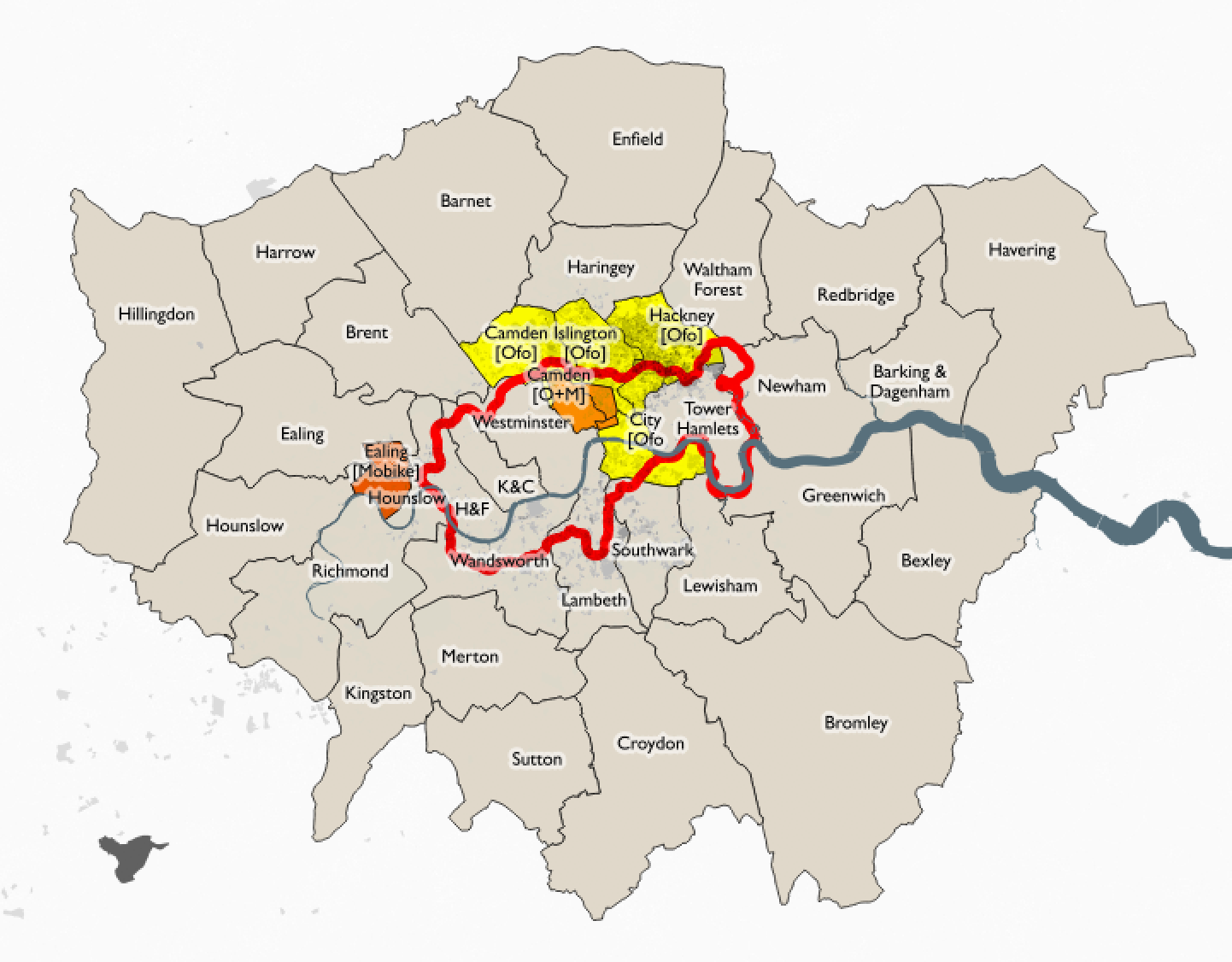

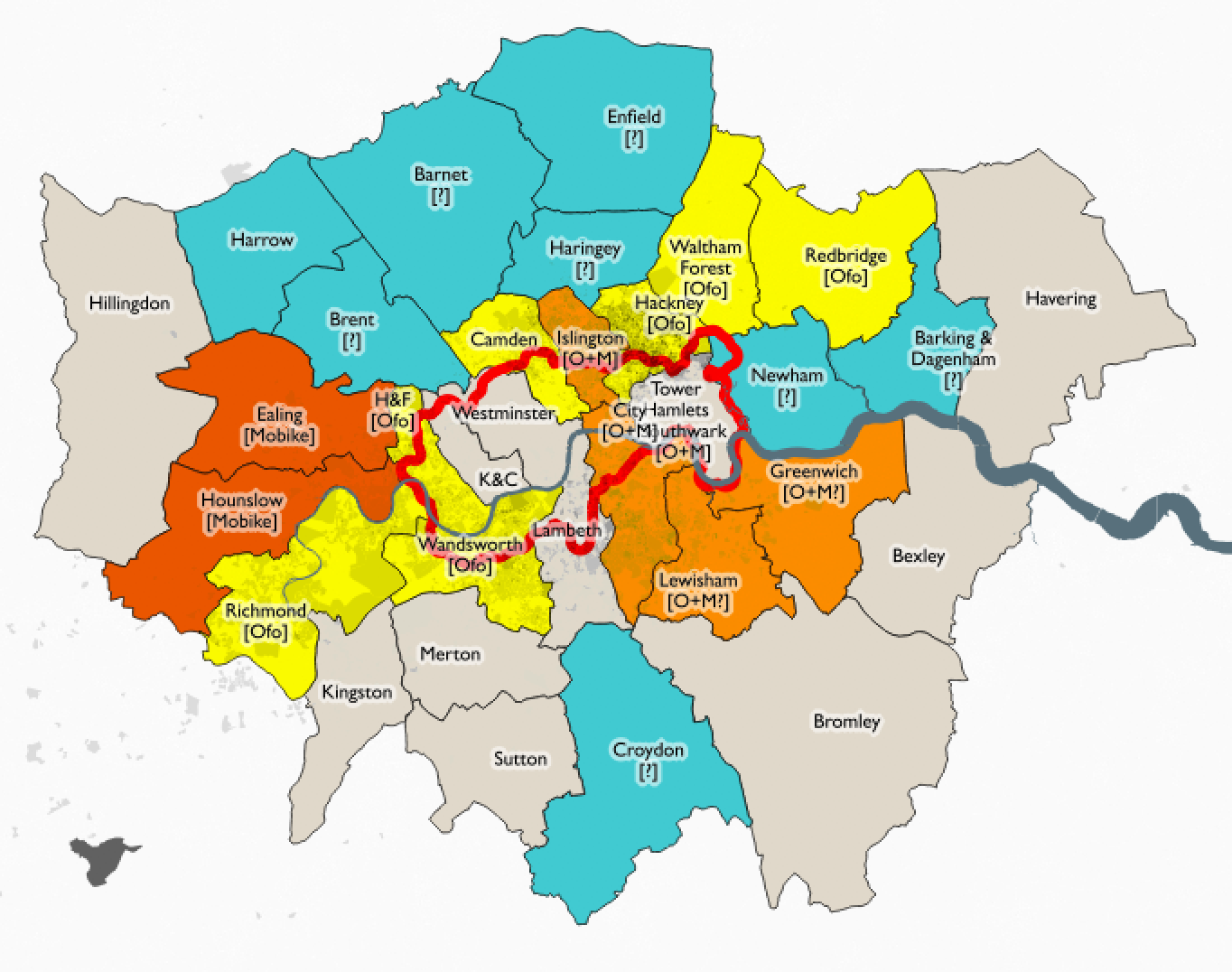

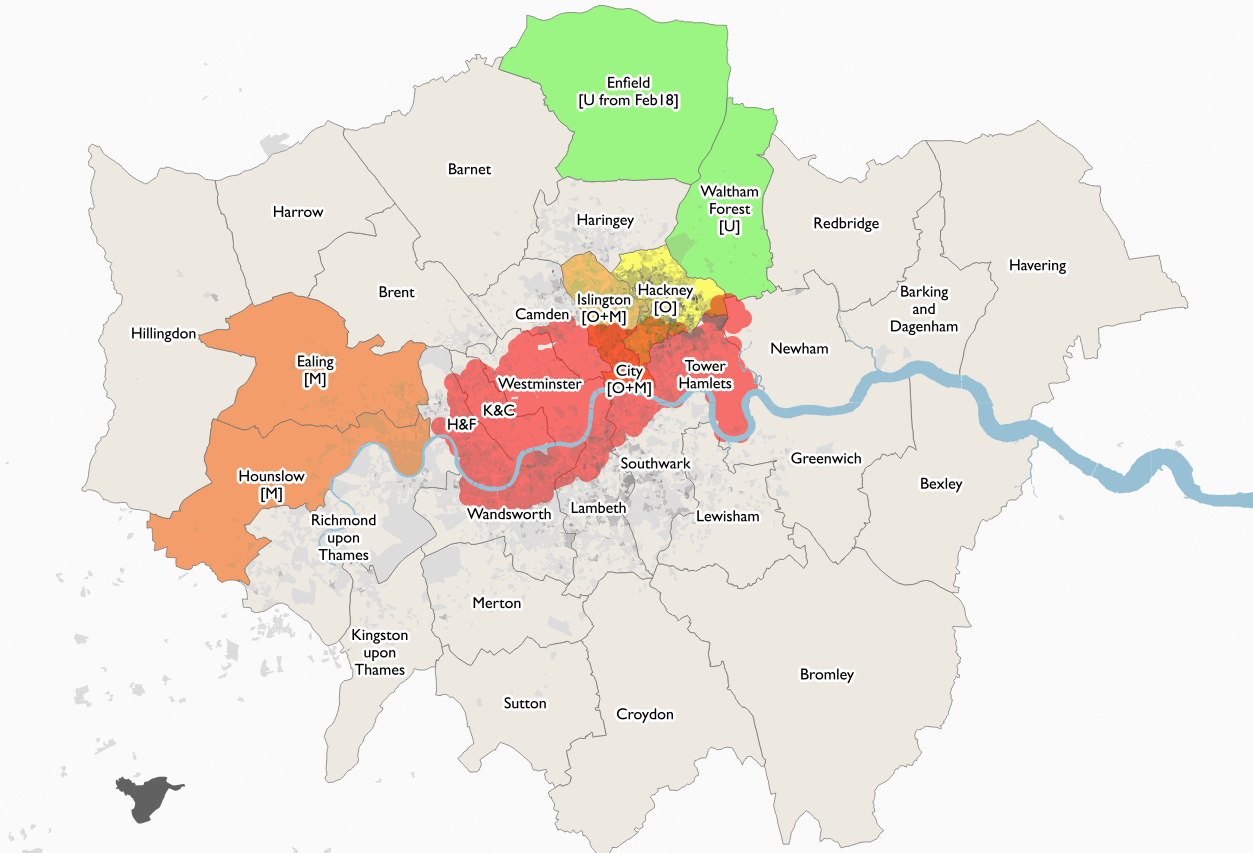

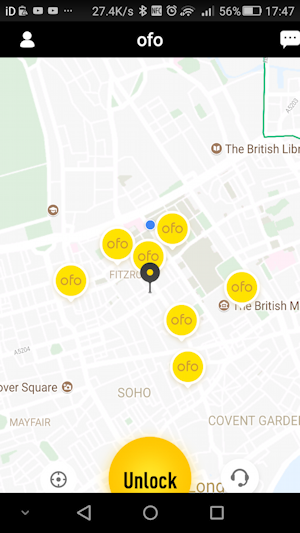

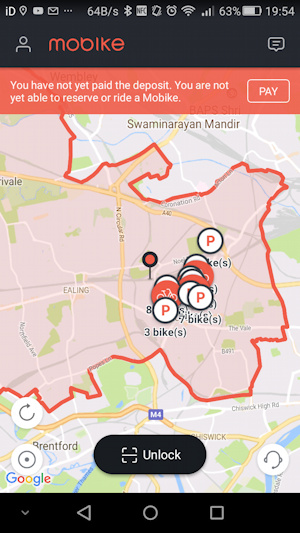

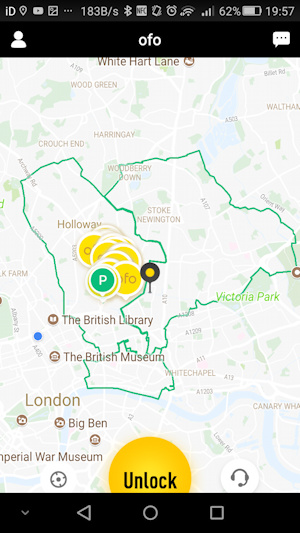

Other players in the space are MoBike (in Manchester), OfoBike (in Cambridge – N.B. website currently down) and YoBike (in Bristol). Another company, GetBike, claimed to have launched in London a few months ago but the bikes, to date, have not appeared. Possibly, they got mired in council discussions. MoBike is also launching a system in Ealing, west London, at the end of the month. All five companies are based in Asia, where mass cycle manufacture is cheap, which had led some cities there ending up with huge heaps of dockless bikeshare bikes, being piled up by desperate city councils trying to keep their pavements clear.

As the bike is the only physical presence on the street, there are no permanent structures for the system and so authorities are not always involved in the process, but have to pick up the pieces and clear the streets – leading some in the dock-based bikeshare establishment to term the systems as rogue bikeshares. The European Cyclists Federation have this week published this timely position paper, where they term the systems slightly more politely as “unlicenced bikeshare” and suggest a potential framework to make the concept work in a European urban context. Whether the operators take notice of course is another matter…

Meanwhile, oBike’s rollout continues. In the map below, red dots with yellow borders show the most recently organically moved bikes (i.e. areas of red/yellow = popular use) while the blue dots with turquoise borders show ones which have not moved since their initial deployment. The other bikes (which someone has moved, but not recently) are shown with purple dots. The map is just a snapshot, and is manually created by myself, so I may have missed some bikes (but I think I’ve got almost all of them):

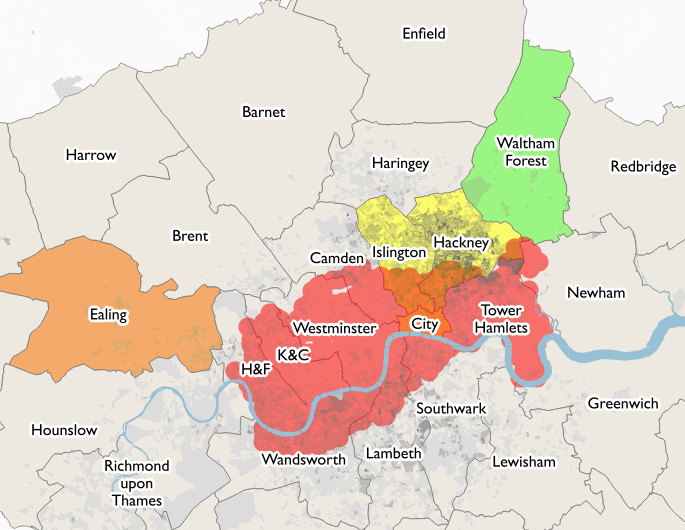

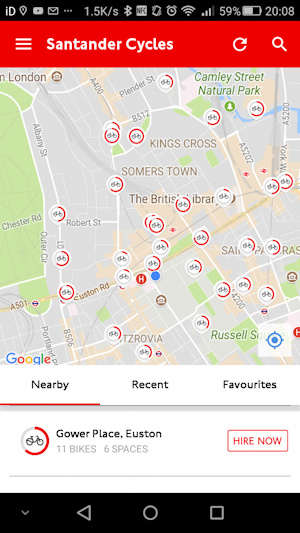

So far, most of the rollout has been to areas already served by bikeshare – the Boris Bikes (aka Santander Cycles). The real value add for London will be when Zones 3-6 (i.e. non-tourist, non-hipster “real London”) get the bikeshare. After 7 years of the Boris Bikes and no sign of them extending outwards, it’s about time the rest of us got the value of bikeshare too, particularly as our alternative options are more limited.

What is it?

Dockless bikeshare is different from the so-called “third generation” dock-based systems like London’s existing Santander Bicycles or “Boris Bikes”. It does away with docking stations and credit card terminals for charging and storing the bikes and administering the access, instead the bikes themselves have locks which contain a solar panel GPS receiver and SIM card for broadcasting their location, and are controlled by an app on your smartphone. It massively cuts down on the costs of the system because no docking stations are needed. London’s docking stations are very expensive as they have to go through the planning process, and also need to be wired up for power. There are also fewer staff needed – oBike do not employ drivers to redistribute the bikes, and also don’t have an established call-centre. Payments are handled entirely through the app. Maintenance teams are also, I suspect, likely to be minimal on the ground.

The bikes themselves are similar in size to the Boris Bikes, but come with solid rubber tyres (so no punctures). They feel around the same weight. The bikes only have only one gear, set quite low, so you can’t get up much speed. The bikes don’t feel heavier than a Boris Bike. They have the same, chunky “tank” feel to them and feel sturdy – the livery being bright yellow helps with visibility on the streets, which is a bonus.

Trying it Out

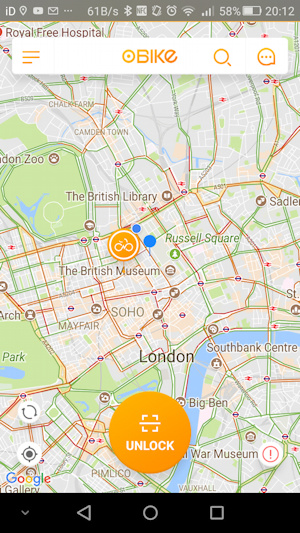

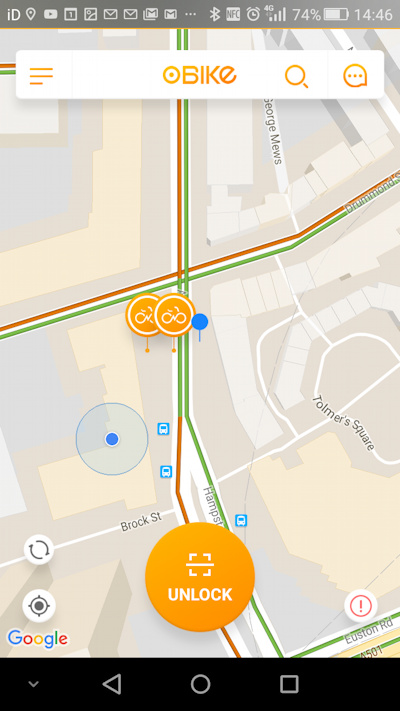

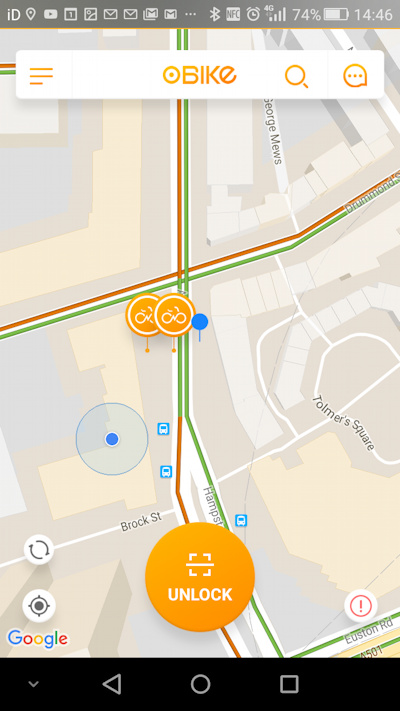

I took an oBike out for a spin yesterday afternoon. I noticed a pair parked (orange pins) close to the Facebook office at Euston Square – maybe some Facebookers trying out the latest thing?

On arrival, I was a little surprised to see the bikes were parked on the other side of the road (small blue pin). Still, my own phone’s GPS was saying I was on the other side of a large building (blue dot)…

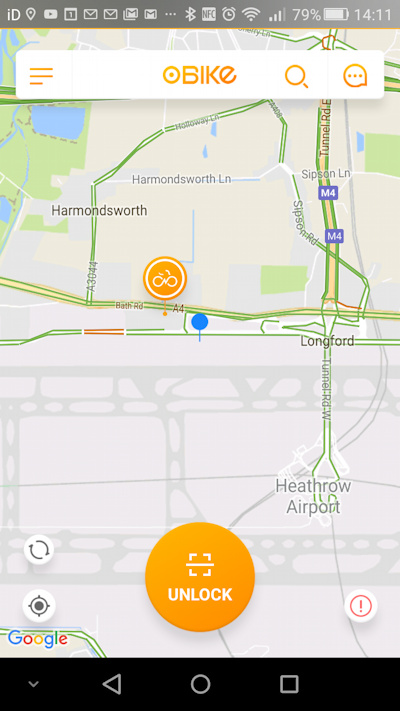

The process of getting the bike was straightforward – I had already paid the £29 refundable deposit (£49 from August) by entering my card details into the app on my phone, so it was just a case of clicking “Unlock” and the scanning the QR code on the bike’s stem. Around 10 seconds later (with communication through your phone’s Bluetooth or through the SIM card on the lock – I’m not sure) the lock on the bike clicked open and the app’s timer started. Neat! The whole signup process was far more streamlined than with the Boris Bikes, where you have to go to a docking station, use the terminal there, page through tens of screens of information and put in your credit card at least twice. Here, you can be on board in less than a minute, with subsequent hires even quicker.

My bike already had its seat raised to the highest position (or higher still, as there was some brown scuffing there) so no adjustments needed. I headed across Euston Circus and down to the British Museum. Unfortunately, my bike had a distinct squeak every time the back wheel rotated, although squeezing the brake stopped it for a few seconds. The brakes themselves are excellent (perhaps I noticed this particularly as my own bike brakes are poor) and everything seemed OK. The bike appeared in good condition, no rubbish had collected in the basket. The handlebars are very wide, so I couldn’t squeeze through the usual gaps between cars and buses. I didn’t find the handlebars very grippy – they are plastic rather than rubber, and my left hand slipped off at one point (I was juggling a mobile phone at the time). In all, not the fastest cycle but perfect fine for utility riding and definitely still faster than walking or getting the bus.

There were various Boris Bikers around, I must have passed at least 10 in my 15 minute ride, but no other oBikes – yet! At the end of my journey I dropped the bike beside a bike rack beside Euston Square station. It wasn’t immediately obvious how to end the journey – you don’t press anything in the app, instead you pull the lock switch manually back across the back wheel, until you hear a reassuring click. A few seconds later, as long as you have Bluetooth switch on, on your phone, then the app beeps and confirms the journey as complete.

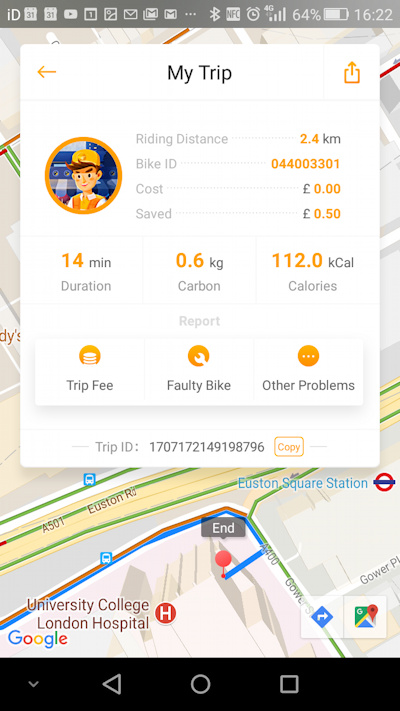

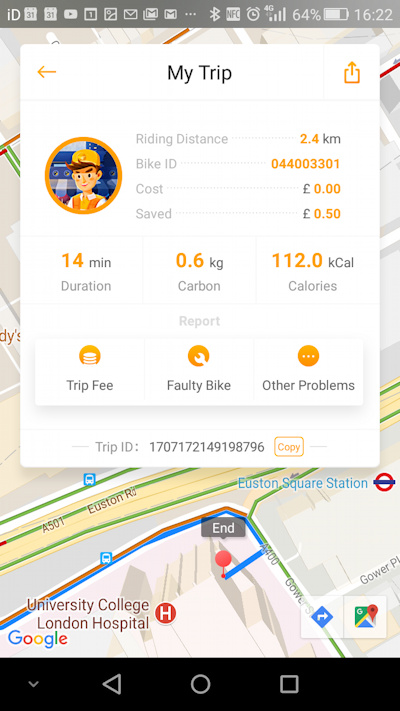

On finishing, the app presents an attractive display showing your start and finish, time, and a “route”, however the route is simple the Google Maps route for bicycles rather than the actual journey taken. The distance also bears no correlation to either the Google Maps “shortest path” route on the map, or the actual distance taken, which is very odd. For the finish location itself, the GPS had once again not given a particularly accurate result, and it looked like I’d cycled the bike straight into the A&E department at University College Hospital. Only 100m or so off again, but not ideal for discovery:

I tried another bike out a bit later. This didn’t have a squeak, however the basket was tilted slightly to one side – not a biggie but still a bit worrying that quirks like this are appearing so soon into the deployment. The bike coped just fine with the rough surface on the River Lea towpath, including over several speedbumps. However, on a return journey, the unlocking process proved to be rather fraught. The QR code was read fine by my phone, but the communication to the lock was not working well, and it kept timing out. Only after around 6 attempts, including moving the bike around. The area we were in had quite poor mobile reception so this may be part of the problem. Still, the few minutes delay to the journey was frustrating. However, once we were moving, the bike itself performed well.

Opportunities

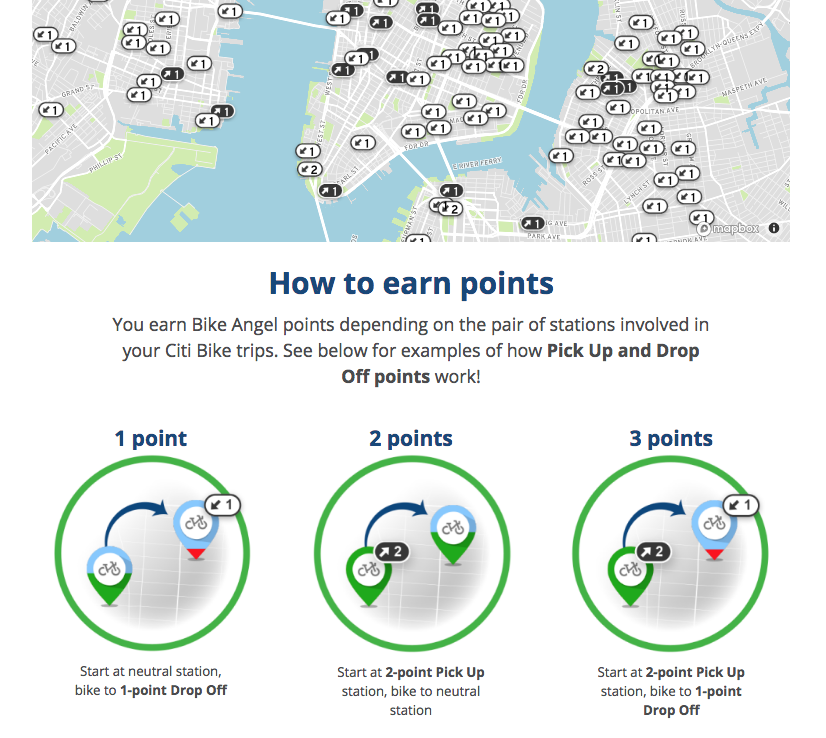

I really like the app, and the payment structure is excellent – 50p flat rate per 30 minutes represents much better value than the £2/day for 30-minute-max journeys on the Boris Bikes. I really didn’t like that, before oBike, it was cheaper to get a bus than a bicycle in London. The reward system is a great idea, it always made sense to incentivise riders to do the tasks of the operator, and the lack of redistribution is another good thing – I always thought it was a huge waste of time redistributing bicycles to one place, only to redistribute them back later.

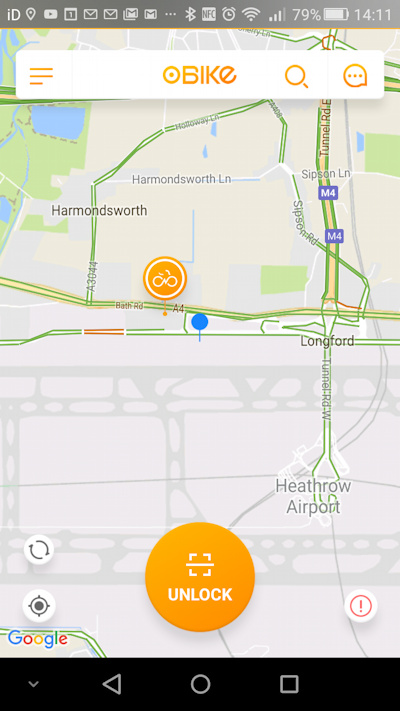

The fact that, rather being constrained to docks, the allowed operating area is the whole of London, is great. Already, one bike has ended up at Heathrow in the far west of London:

The lack of docks mean that the users set the area of coverage. Finally, Hackney and Haringey, Lewisham and Rotherhithe, have the bikeshare that I am sure would always have been popular there.

I do also like the name – oBike (five letters, two syllables) rolls off the tongue a lot more easily than Barclays Cycle Hire or Santander Cycles.

Challenges

I’m not totally convinced that oBike will survive long-term – despite assertions to the contrary by some operators of these dockless bikeshares, the bikes will need maintenance due to the rough weather, roads and people in London. Whether they get any will be interesting to see. The bikes I tried out have only been on the streets for four days, and for the first one I tried have picked up a loud squeak so quickly, and the second one to have a wonky basket, is not great. The bikes are also a little too small for the British frame – having said that I am 6′ and I got around OK on one, but with the seat-post extended to its absolute maximum. There have been some cases of the seat-posts easily coming right off when extended further.

Also – some people will inevitably be hard on the bikes. They are not that indestructible, and some people will see them as a cheap way of getting a bike. Some will end up in the Thames. Councils will end up confiscating some, as Hammersmith & Fulham has already threatened to do. Not getting the council involved is brave – they may have looked at the Cambridge example where the council insisted that another operator reduce its launch from 500 bikes to 20 – there are obvious advantages with not having to deal with 33 separate councils in London (+ the City + TfL and the GLA) and just sticking the bikes out there – but oBike could have made life easier for themselves by distributing them more discretely, to avoid the ire of grumpy councils and pedestrians – placing one or two bikes together, at the most, ad on side roads rather than main roads, beside existing cycle parking racks, rather than obstructing pavements, and focusing on Zones 3-6 first (even if that results in a slower initial takeup). And a commitment to maintenance or organised disposal would also be good – at the moment no one knows what will happen to the bikes after they start to wear out. The scenes of “bicycle graveyards” and huge heaps of brightly coloured bicycles, in the cities of the far east that are full of dockless bikeshares, are worrying.

I hope that oBike is a success, and the bicycles survive grumpy councils, the kids who just want a free bike, and the weather. If it provides an incentive to give the Boris Bikes a kick up the backside (50p per 30 minutes flat rate and all-London low density coverage please!) then that on its own would be a result. Providing a bikeshare out into London’s Zone 3 and further is a real winner for shared mobility options outside London’s already well connected central core.

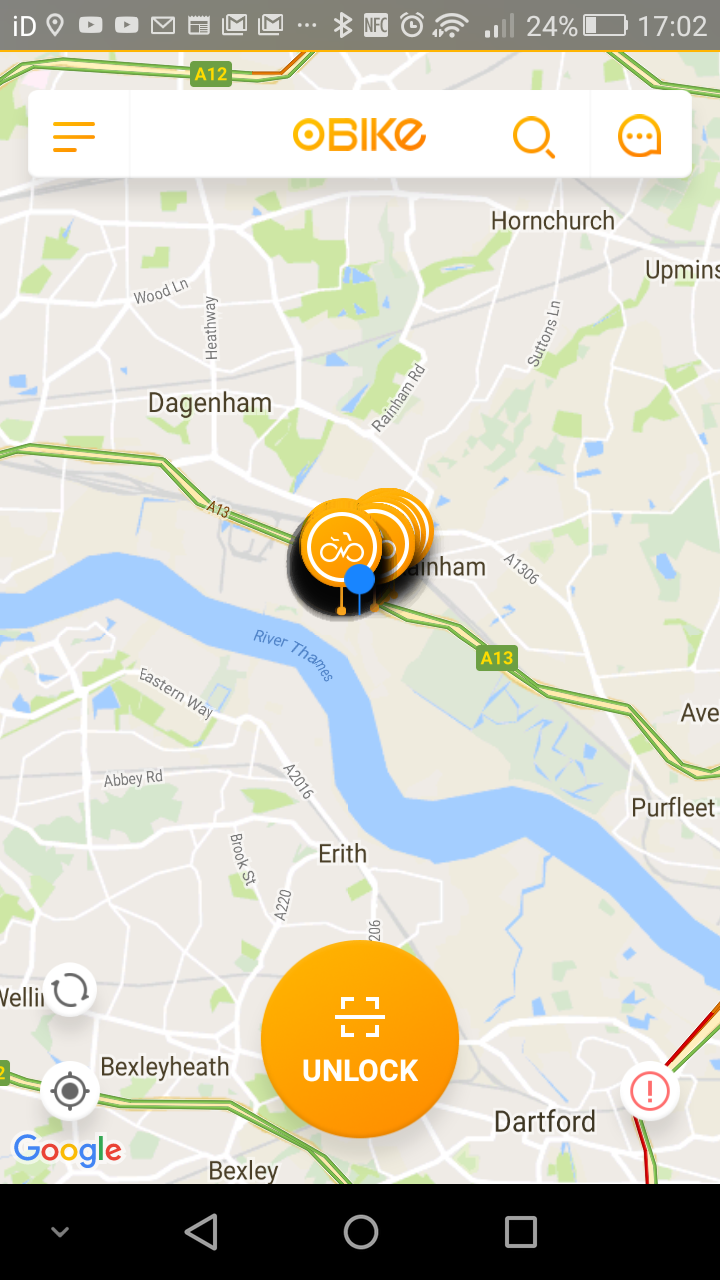

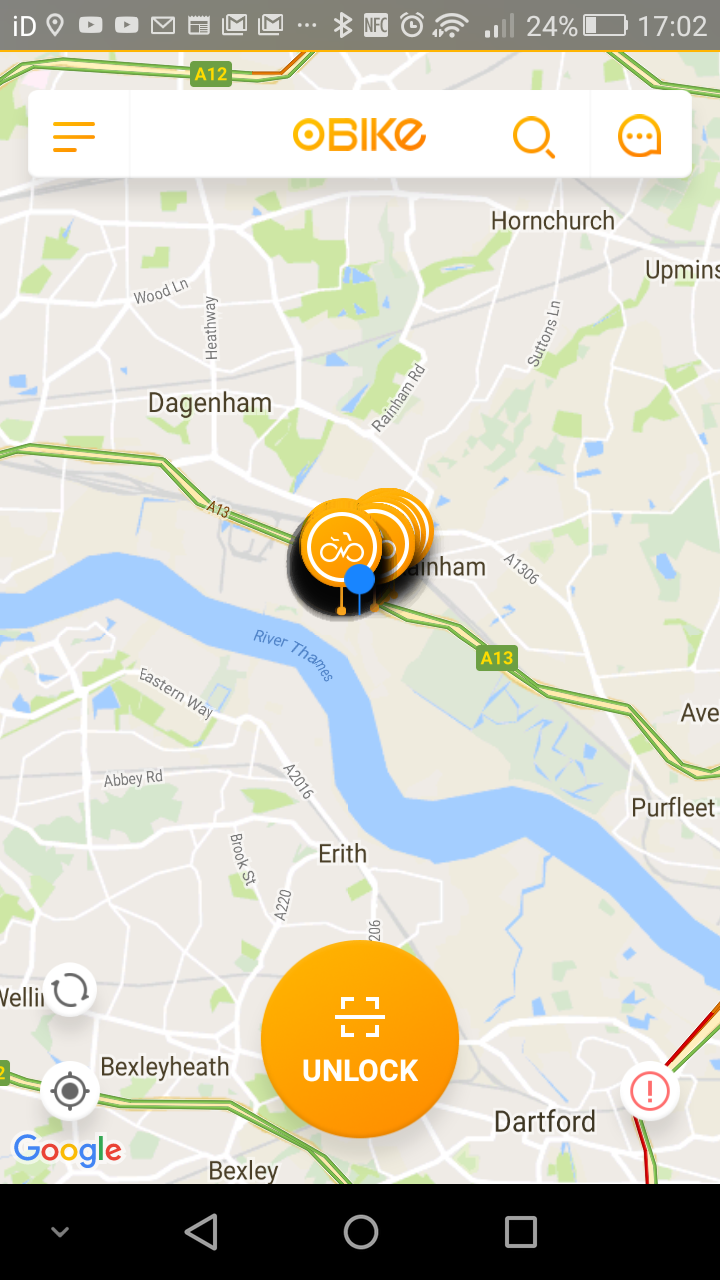

* These have since been removed, I understand, following discussions with the councils there. The company however did not switch off the GPS trackers on the removed bikes, and so have revealed the location of their depot, at Rainham on the very edge of east London:

Map background Copyright HERE Maps. Top photo Copyright JC, bottom photo Copyright SR.

Photo: Copyright TfL.

Photo: Copyright TfL. Santander Cycles last week

Santander Cycles last week  The Ealing launch had a reported

The Ealing launch had a reported

I have ridden an Ofo bike (a one-off in

I have ridden an Ofo bike (a one-off in  Photo:

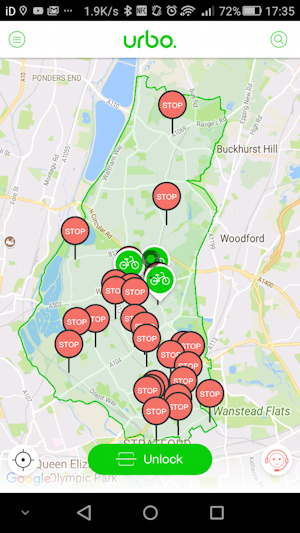

Photo:  Like Ofo and Mobike, Urbo have designated zones in their host boroughs and induce users (via cheaper journeys) to end their journeys in these zones (shown with the STOP icon on their app’s map, here). These zones come with a bespoke street sign erected by the local authority, as well as the usual taped/painted markings on the ground. It is a little surprising that Waltham Forest have included the operator logo on the signs (presumably to Urbo’s delight) as there is no good reason why other dockless systems, when they inevitably arrive here too, should use these spaces too. It is kind of like the council painting new car parking spaces on a street and putting up a sign, with the Ford logo, saying they are spaces for Ford cars only. They are just spaces on a road/pavement…

Like Ofo and Mobike, Urbo have designated zones in their host boroughs and induce users (via cheaper journeys) to end their journeys in these zones (shown with the STOP icon on their app’s map, here). These zones come with a bespoke street sign erected by the local authority, as well as the usual taped/painted markings on the ground. It is a little surprising that Waltham Forest have included the operator logo on the signs (presumably to Urbo’s delight) as there is no good reason why other dockless systems, when they inevitably arrive here too, should use these spaces too. It is kind of like the council painting new car parking spaces on a street and putting up a sign, with the Ford logo, saying they are spaces for Ford cars only. They are just spaces on a road/pavement…