The GLA published an interesting report last week: Future transport – How is London responding to technological innovation. It focused mainly on drones, driverless cars and app-based services (as an example, CityMapper’s experimenting on turning its huge desire-line dataset, created from the data of its millions of users and their journeys, into a group-based taxishare service), but also included some details on bikeshare, and in particular the dockless “revolution” that is currently underway in the capital.

Not Looking Good for Santander Cycles

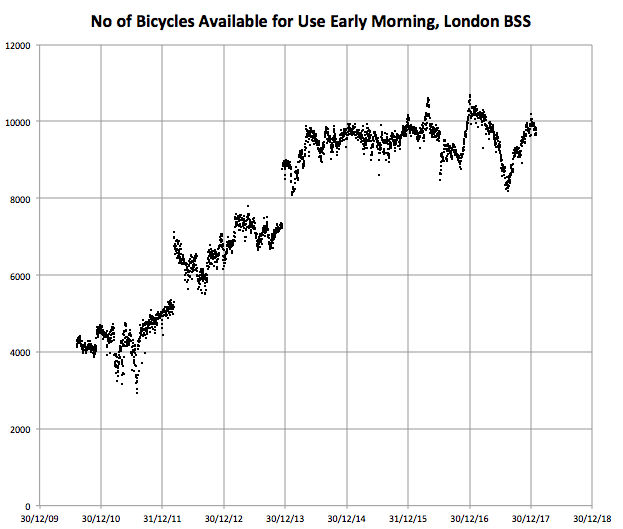

Some tidbits from the report include some depressing news from Transport for London regarding future of the Santander Cycles dock-based bikeshare system – “the scheme is also limited geographically to central London, with TfL having no plans to extend it.” Ouch.

Well, that’s a pity, but not entirely surprising. The reason are both political and financial:

- It was a system launched and promoted by a previous mayor, of the “other party”, who was more focused on cycling and also less afraid to challenge the status quo. The existence of the system (despite its problems), and the associated disruptive – but brilliant – segregated cycle lanes – have been revolutionary. But they will be ever associated with a previous mayor.

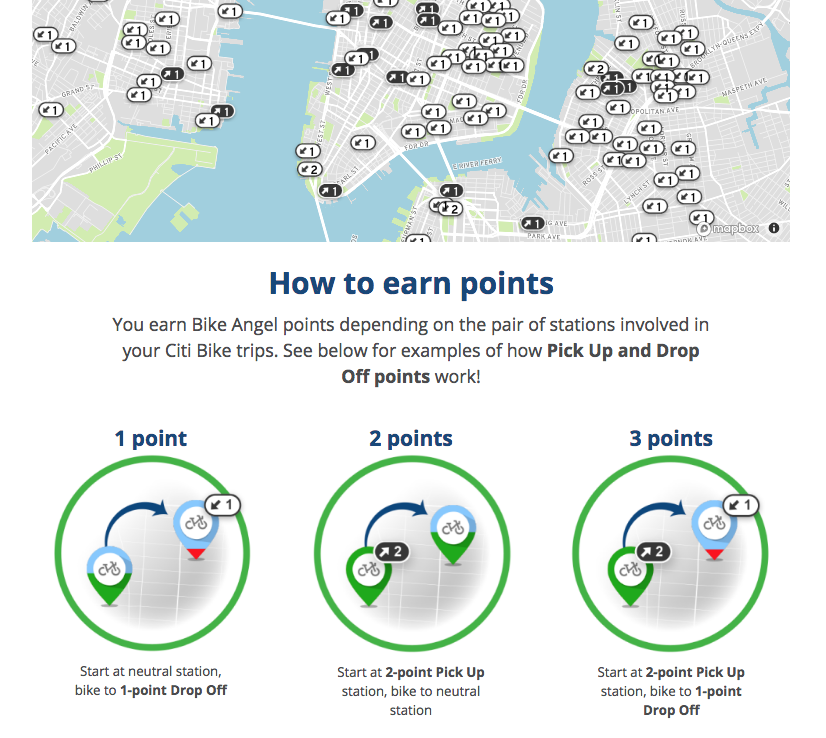

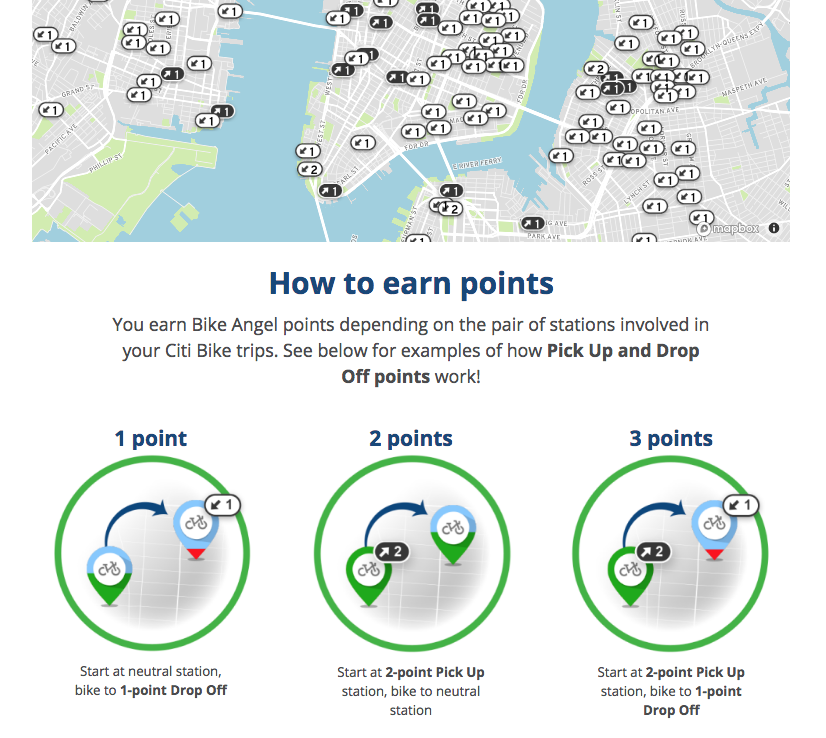

- Also despite the system being almost eight years old, TfL is still subsidising the system by over £3m a year. Too much unnecessary redistribution going on – using vans – presumably because they always have done it or other schemes have. Vans and drivers are expensive! And they clog up the streets. Incentivise users to do their own distribution – by using the bike itself – for rewards – much cheaper! The New York City system has “Bike Angels” (pic below) which actually has pretty decent rewards for riders who rebalance. There has also been an, I think, frankly misguided focus on keeping docking station density unnecessarily high throughout the area, and a focus on journey numbers over user utility, means the main beneficiaries are city workers getting from Waterloo to the Bank during weekdays and tourists circling Hyde Park at the weekends. Both groups have numerous other options, so the bikeshare here isn’t really solving any “last mile” mobility problems.

A flat rate of say 50p/20 min or £1/30 min, similar to the dockless systems (generally 50p/30 min), and moving the 20% least used docking stations so they were outside every tube/train station and inside every park and larger open spaces in Zone 2 to provide a ready source of obvious rides, would probably end up being more profitable, as there would be a massive surge in usage (right now it’s cheaper to get the bus!), particularly if it was integrated into Oyster card/contactless and was covered by daily/weekly capping. Why does it need to be profitably anyway? The buses (in London) aren’t, and the bikes encourage healthier outcomes, both to the user and surrounding pedestrians, than sitting on a bus emitting pollution.

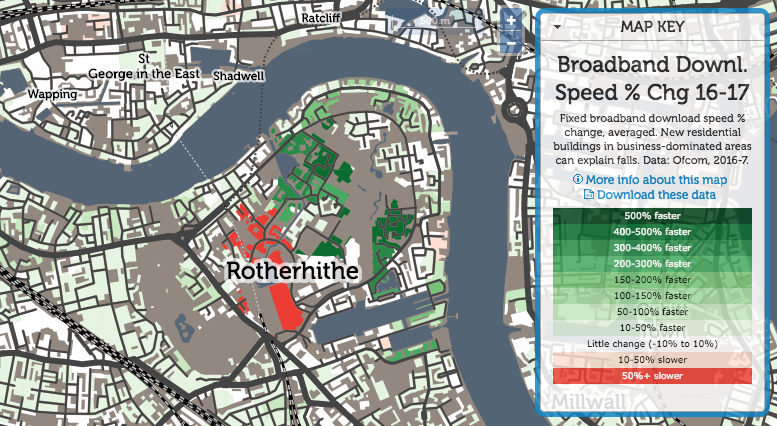

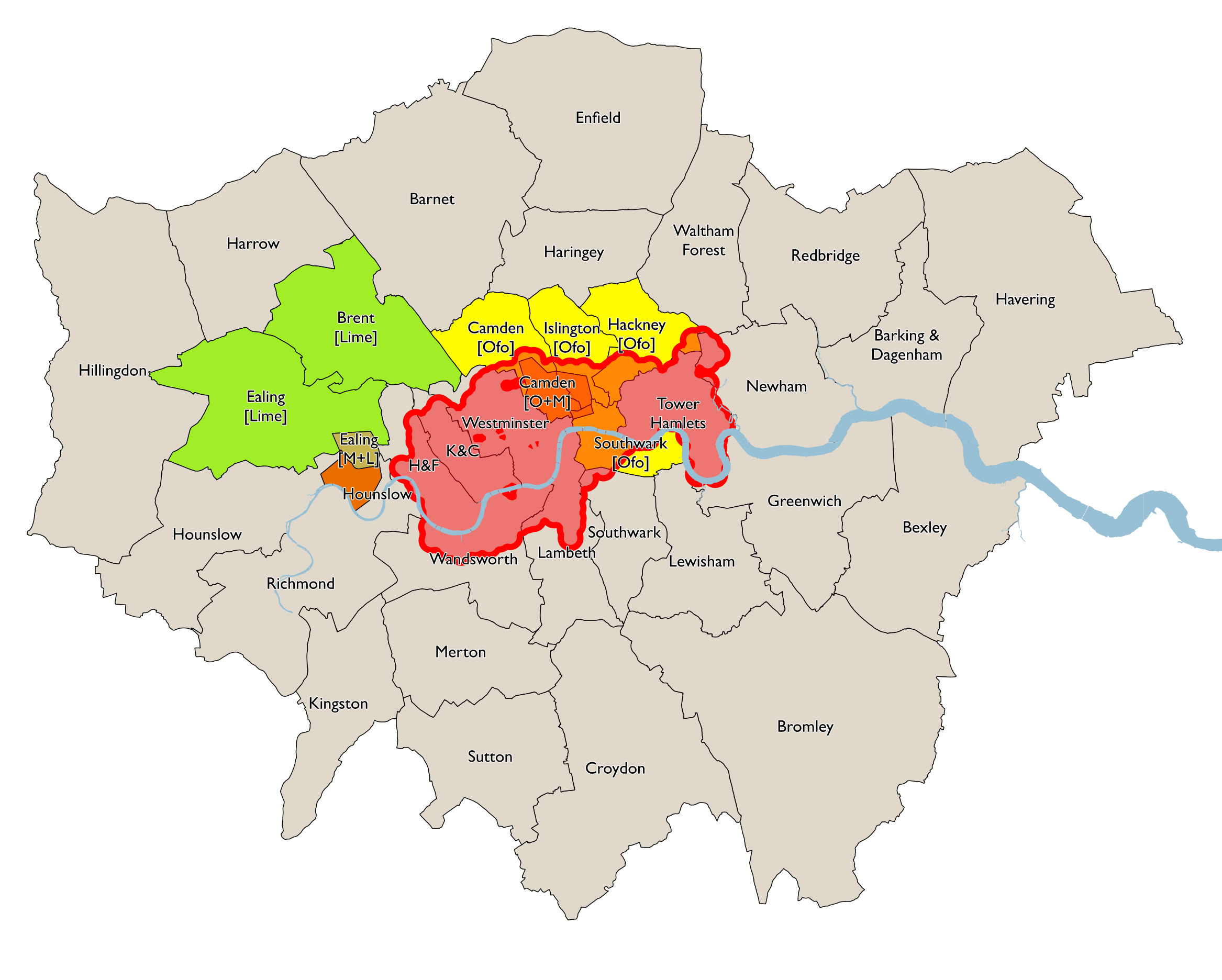

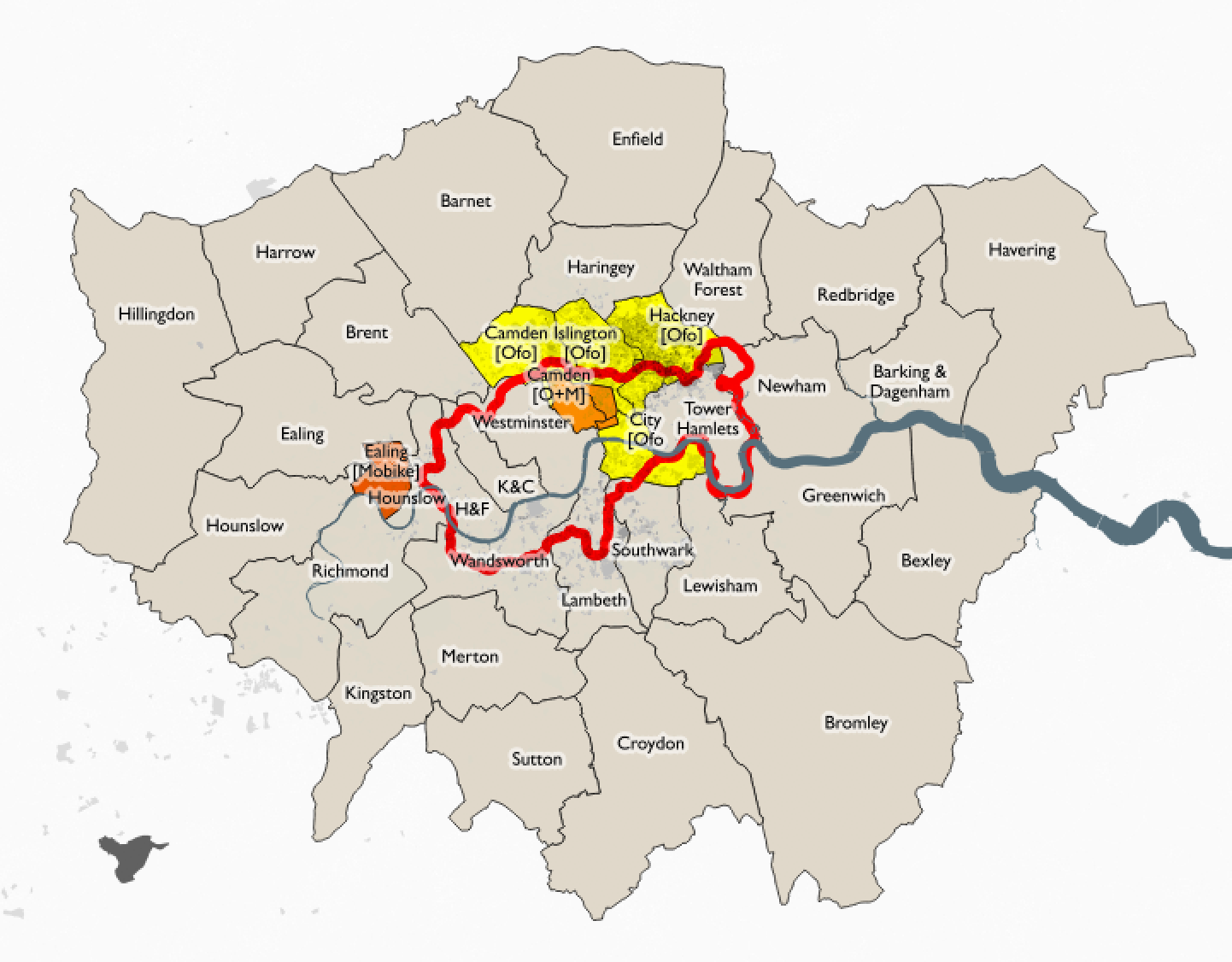

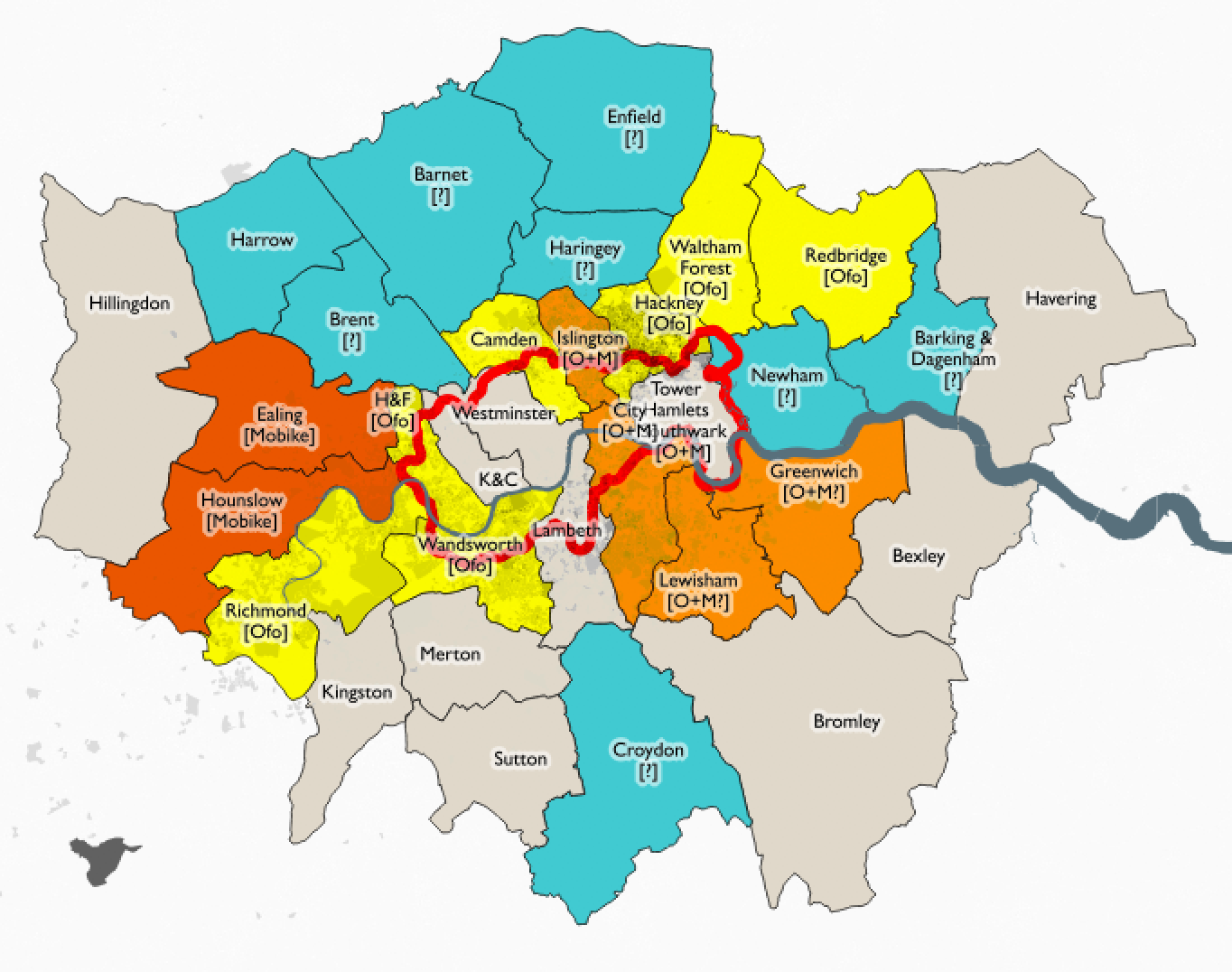

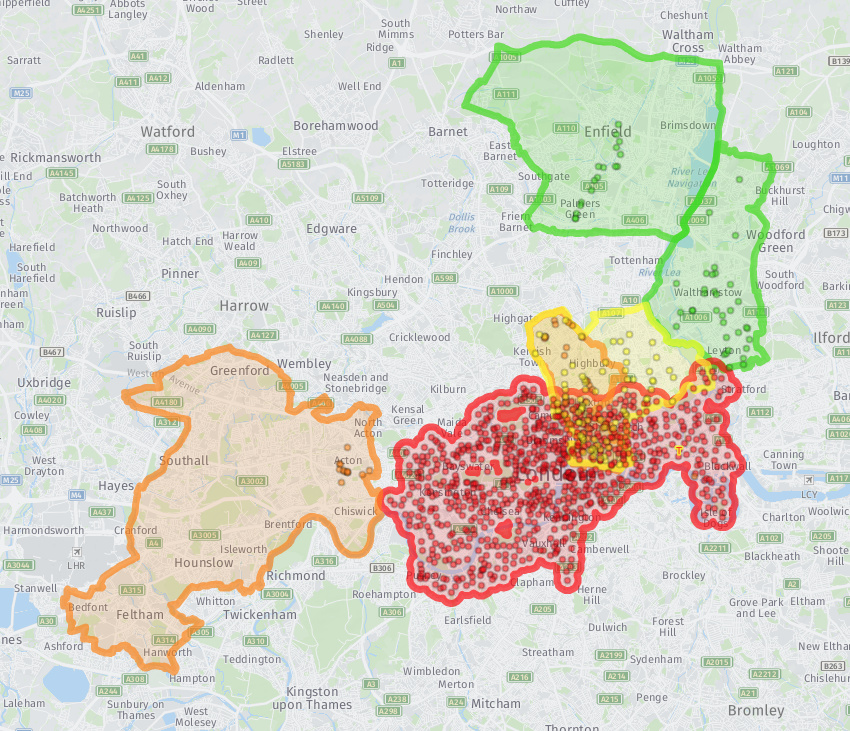

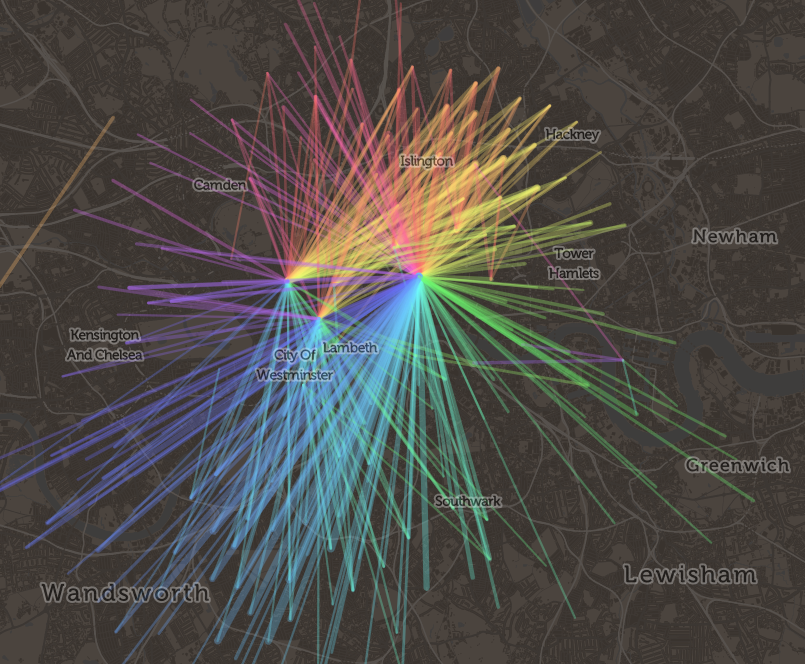

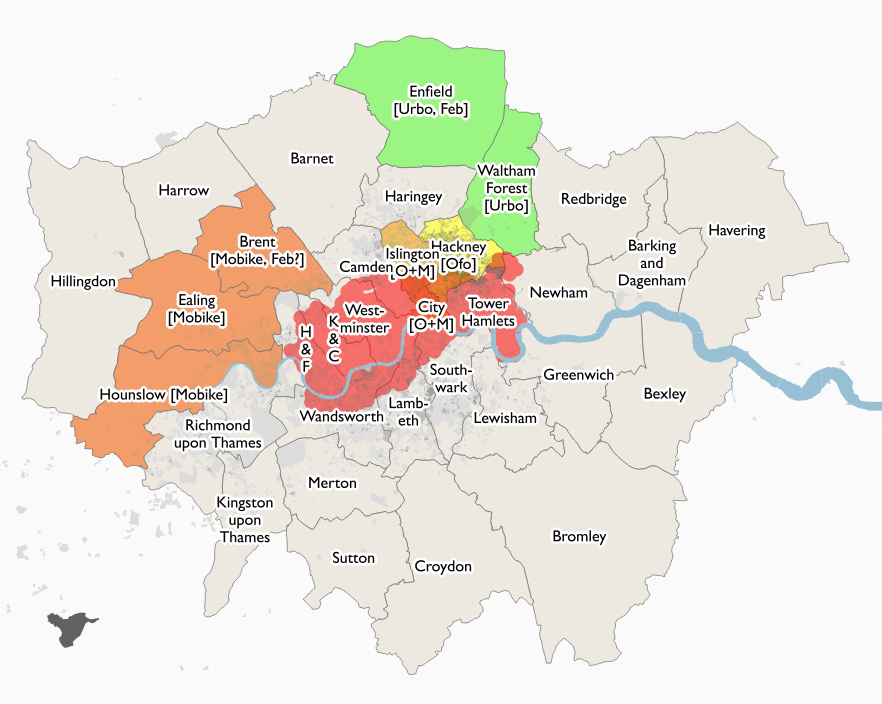

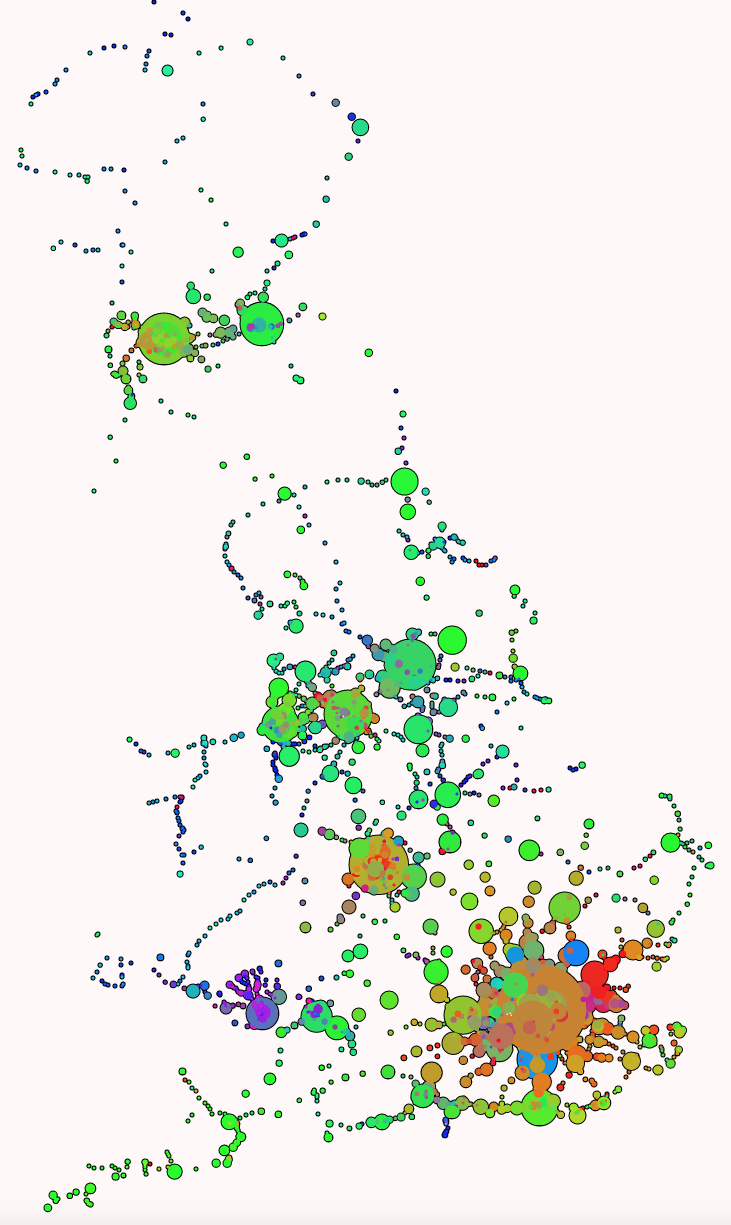

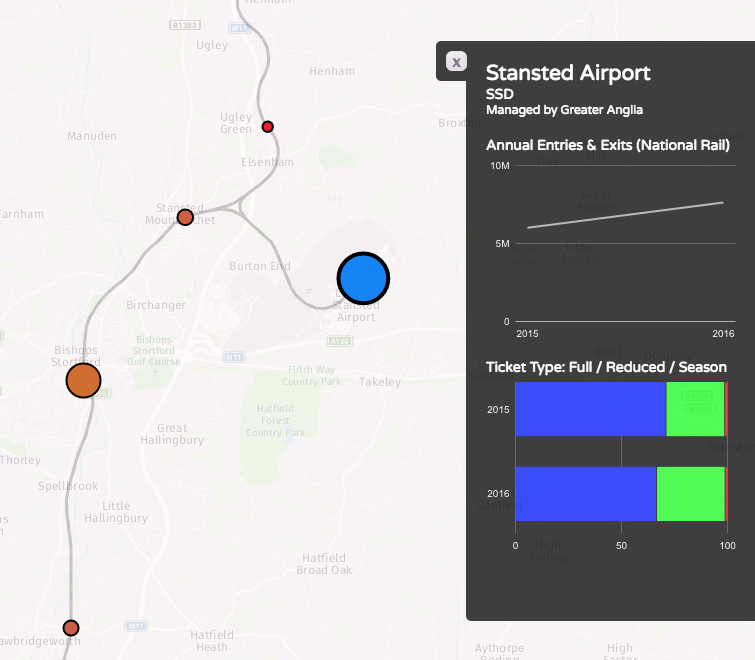

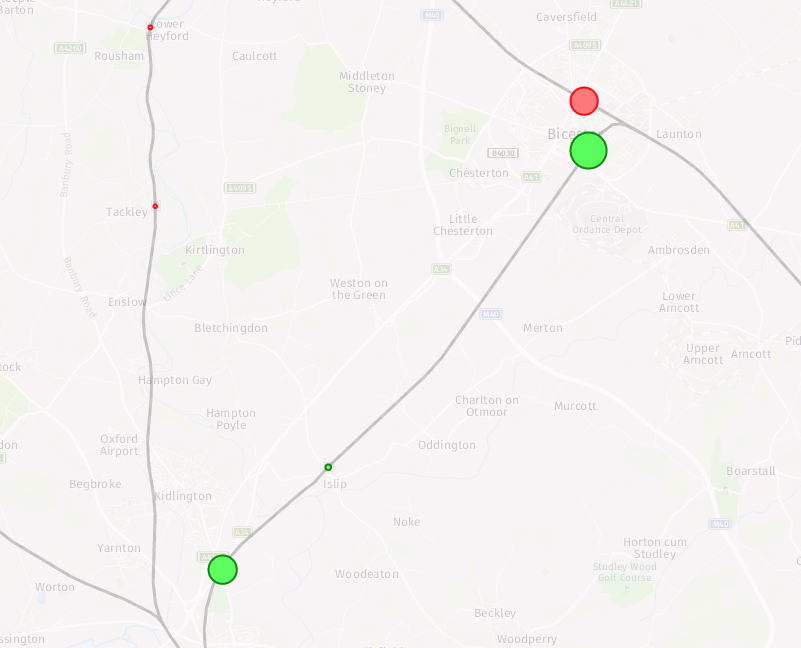

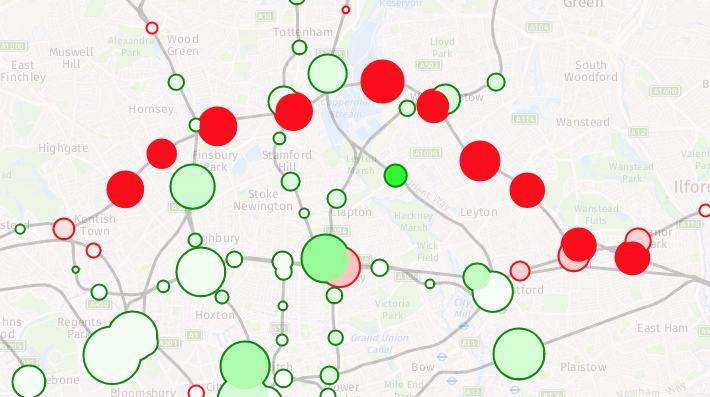

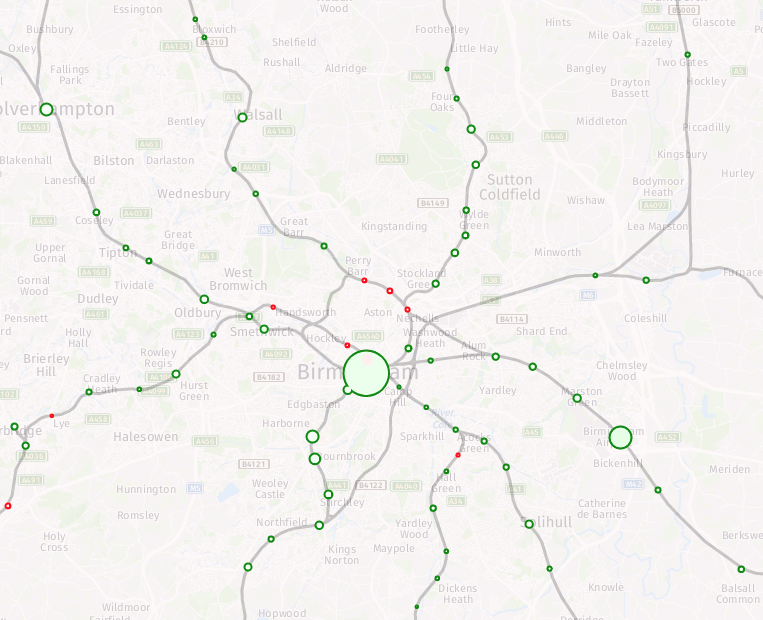

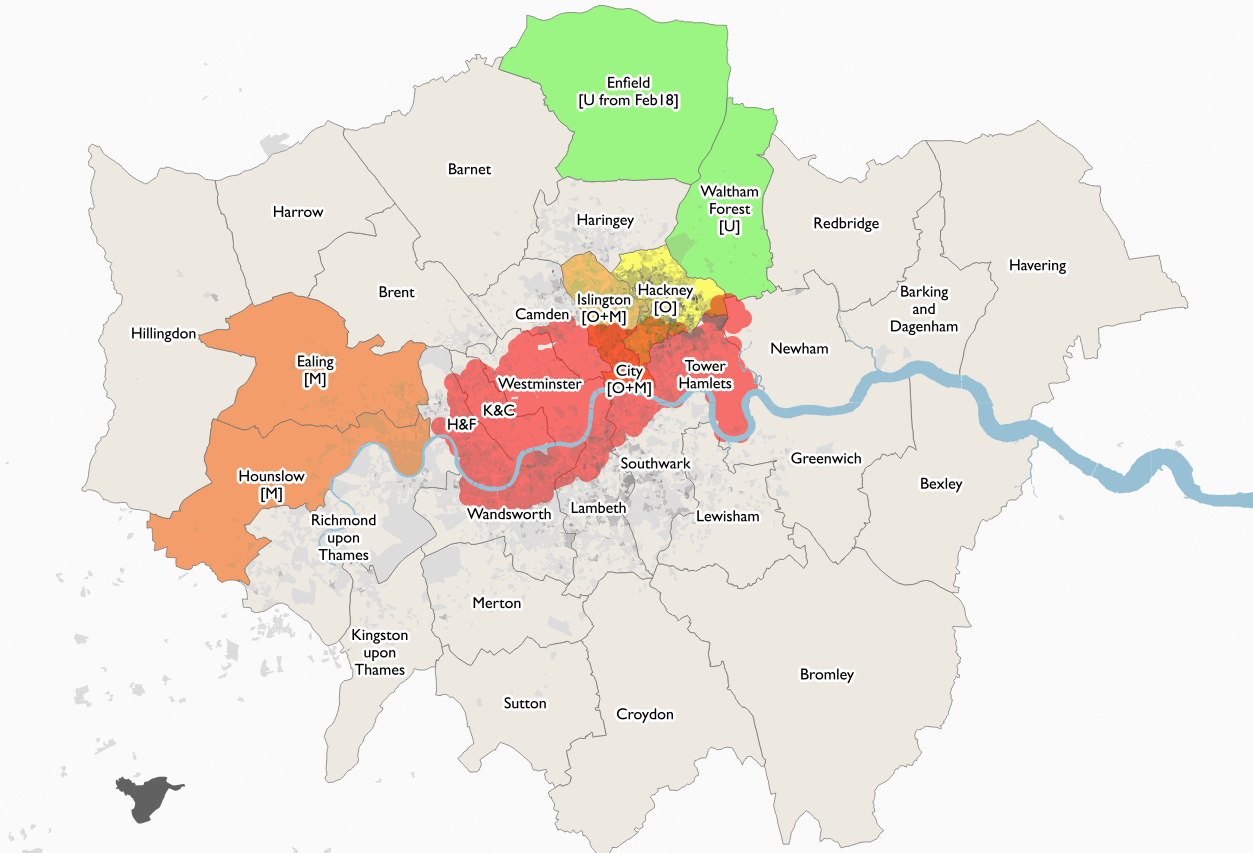

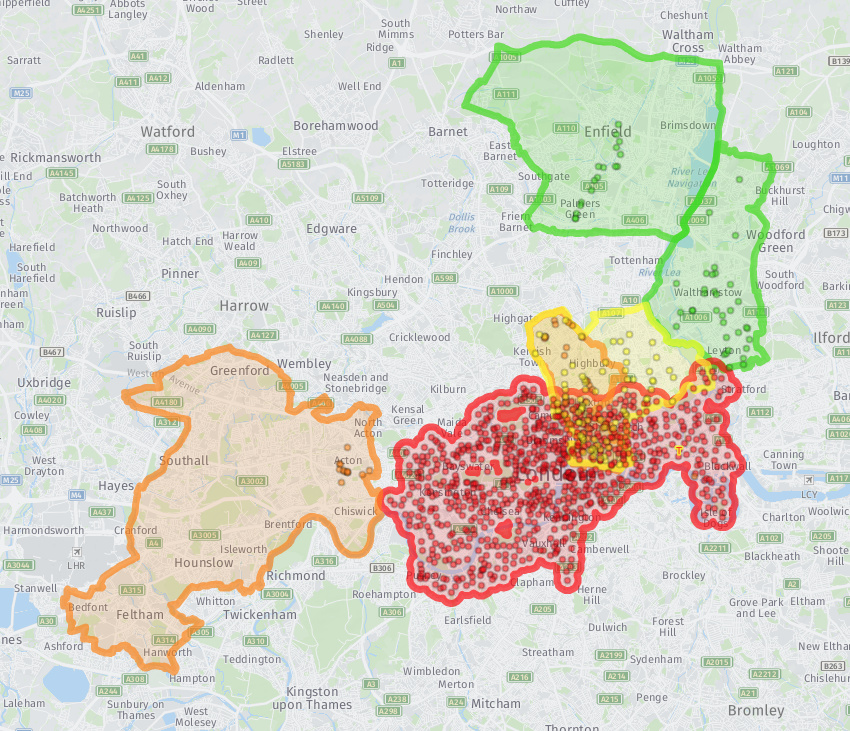

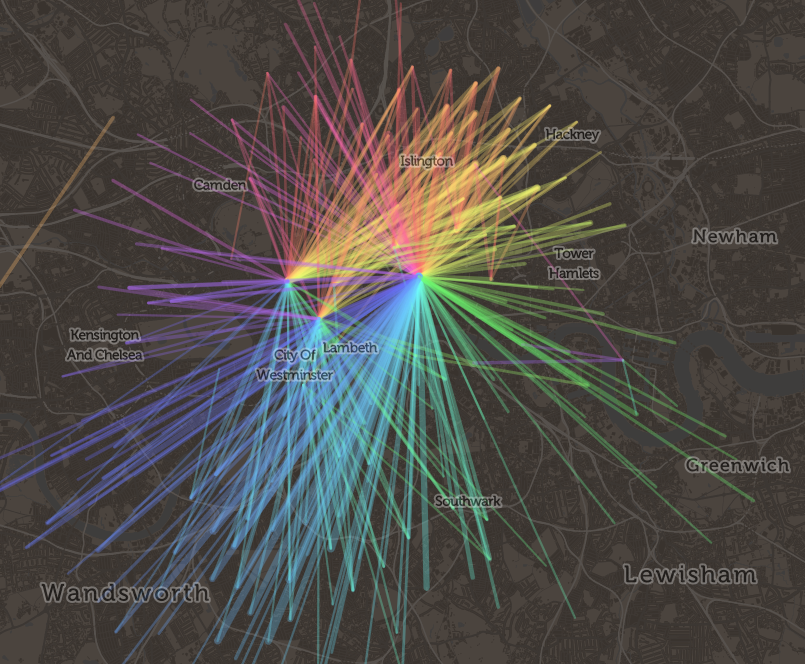

London-Wide Regulation of Dockless

One important point from the report is suggesting that TfL should take the lead in regulating and so controlling the provision of dockless bikeshare systems on London streets, instead of the individual boroughs as present. This is an “obvious” thing to do – it is time consuming and inefficient for each operator to, assuming that they want a pan-London rollout, have 33 sets of negotiations with the 32 separate borough councils and the City of London, when much of London’s other transport operations are specified, operated or regulated by one entity – Transport for London. It also slows the rollout, makes the systems very expensive for operators to maintain if they are fragmented, particularly if each borough has slight differences in their specification (e.g. on maintenance response times). More importantly, it makes it less useful and more confusing for the user – both the start and the end of an intended journey need to be within an operating zone. Borough boundaries are somewhat arbitrary to most people living in London, and not easily noticed when crossing them. “London” is a more familiar area. Most commute journeys in London are radial – going towards or away from the centre (see pic below). The reluctance of many of the operators to even publish their operating zone except on their individual apps, also makes discovering the allowable area of a system – let alone using it – a challenge.

Curiously, a lot of the press leading from this report seemed to suggest that the recommendation of TfL taking on regulation of dockless bikeshare in London was in some way a clampdown on their operations, or a tightening of the environment, and would be therefore bad for the operators and presumably therefore good for those wanting to see these bikes off the streets. Rather an odd, negative spin. I don’t think it’s not that at all. Having TfL specifying and setting operational parameters for dockless systems, rather than 33 geographically limited entities doing so, can only be good for everyone concerned.

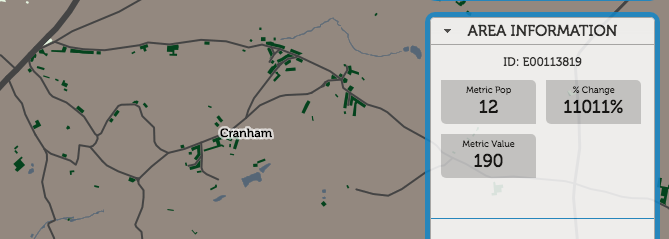

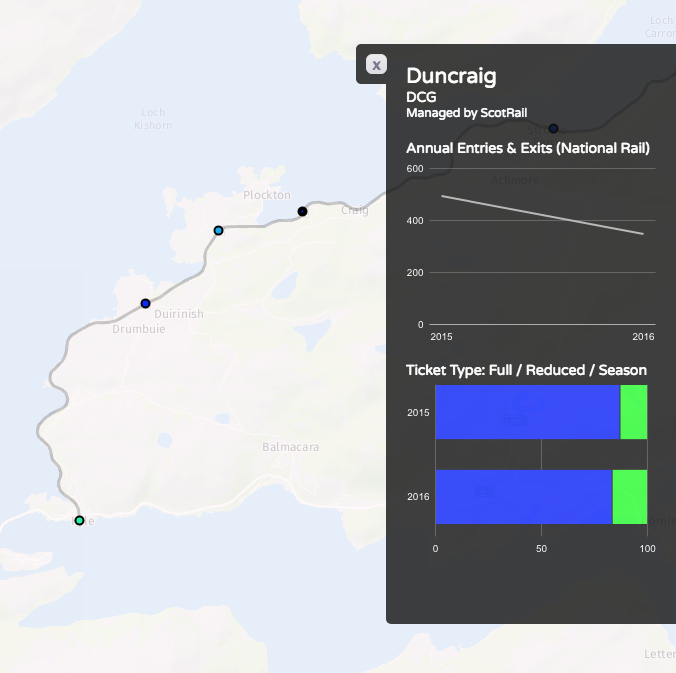

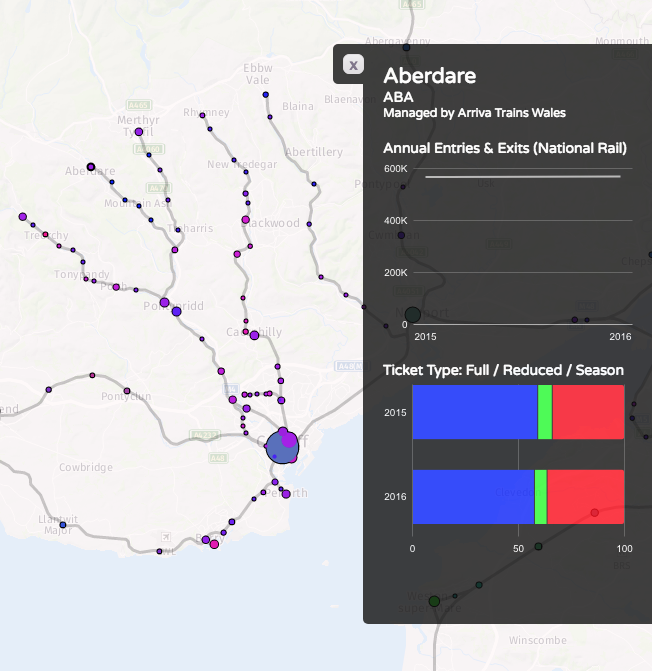

Smarter City? It’s All About the Data

My own take is that TfL regulation would be welcomed, but it should be linked with an incorporation of data into TfL’s own open data platform. A smart city is an open city, one where availability data on useable assets in the public realm is accessible to all, not to those tied to a particular platform (even if the transaction part needs operator control) or hidden to hide poor public value for money or failing/missing assets, as is happening for a system in a certain city up north. There is a need to democratise the information, in order to digitise the city. To this mind, dockless operators should be mandated to open up data on the location of bikes available to hire, hubs (preferred parking areas) and operating zones. This kind of information has generally always been made available by dock-based systems, dockless systems have so far not been compelled to release this as open data yet – at least in the UK.

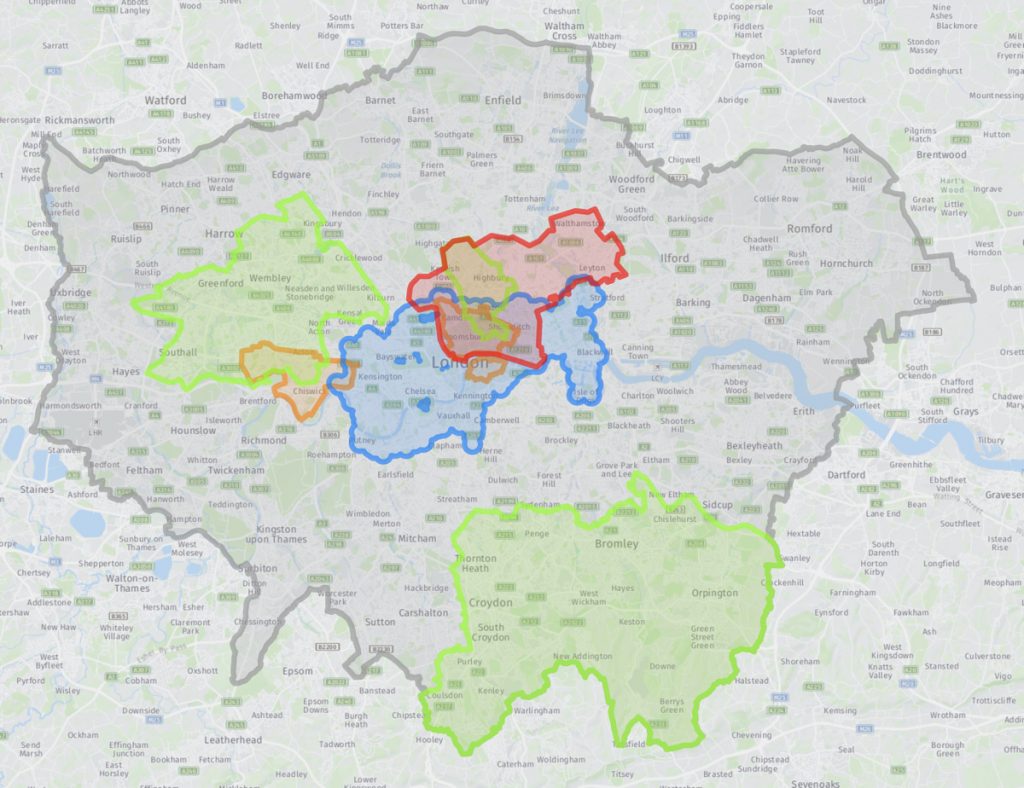

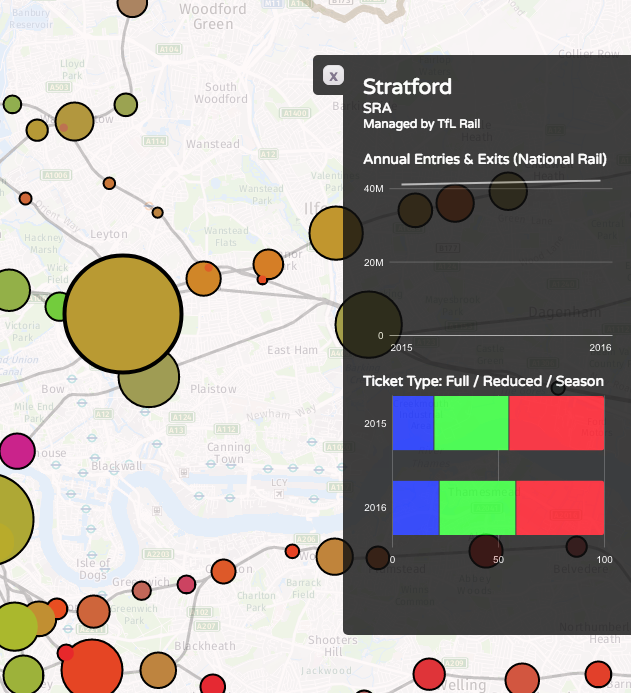

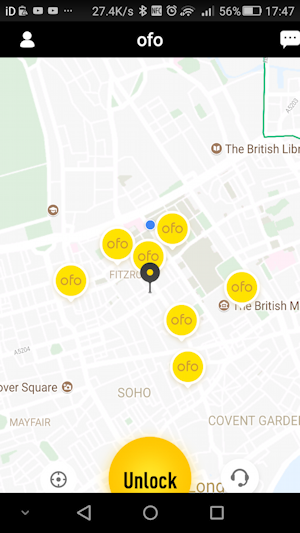

To this mind, I am contemplating launching an operator data openness scoreboard for the UK – similar to one that was unveiled at a recent bikeshare hackathon event in Washington DC. I’ve also put together an interactive map showing the current coverage in London of the four active systems (Urbo, Ofo, Mobike and the dock-based Santander Cycles), plus known “hubs” where you are most likely to find bikes available for hire – N.B. not all the operators are using a hub-based approach across their whole areas. Because of the lack of open API data from most of the operators, much of this map is manually put together and so may be a little out of date – I will do my best to keep it current. The crucial data missing here of course is the current locations of bikes available to hire. For now, you’ll need to use each individual app.

How Dockless Might Work in London

Personally, I think that hub locations are one of the most important features of the new dockless systems. They can act as a point that is regularly stocked with bikes, meaning that regular users might not need to keep doing different journeys on foot to hunt down a bike. They also help the system keep order – they may help to minimise the amount of inconsiderate parking. Currently, the reward for finishing a journey at such a hub is minimal. Operators will have to be more ambitious if the hub-inducement model work. Something like halving the fee to finish a ride in a hub, and doubling it to finish a ride outside of an operating zone altogether. It should also be possible to have hubs outside of operating areas, for example, on specific pieces of private land where access has been granted, but the local authority has not granted permission.

More generally, I think, for large western cities like London, where pedestrian space will always be at a premium, the dockless model, as it stands, will not work. Either there won’t be enough bikes, so that no one uses the system, or the labour costs will be too high for the operators, or there will be too many bikes causing clutter. The system for London that I envisage, will work, is that Zone 1 gets around 1000 “mandatory hubs”, boxes painted on the ground, each around the size of a car parking space but mainly on the pavement, where any cycles from any of the dockless cycles may be left. TfL or boroughs get tough with the operators and users and impound bikes left outside of these zones by users, with operators getting fined for each impound and the operators passing on these fines (should they choose) to the delinquent user. Outside of Zone 1, the system could work as present, with recommended hubs. However boroughs/TfL need to stop operators creating hubs branded with only their own logos and signs, and instead create generic hubs. They can still just be painted lines on the ground – the bikes themselves should be all the branding needed.

See also my borough by borough scores, or the interactive map.