I’ve been based at the ESRC Consumer Data Research Centre, a multi-university (UCL/Liverpool/Leeds/Oxford) lab focused on research and provision of specialist UK consumer datasets, since 2015. One of my first outputs was to adapt DataShine, which I’d created in 2013 as part of a previous UCL project, to produce CDRC Maps – to map some of the open datasets we held, and aggregates of some of the more interesting socioeconomic datasets that we produced from the controlled collections.

CDRC Maps is an OpenLayers-based “slippy” (pan/zoomable) map website consisting of pre-rendered raster tiles of choropleth maps of consumer metrics, layered under another raster “context” layer containing roads and labels, and a mask which results in only building blocks being coloured by the underlying choropleth. It served its purpose of showing impactful, pretty and effective maps of our UK socioeconomic datasets, but being a raster based map, with billions of tiles sitting on one of our old servers, it has been showing its age for a while.

The modern web mapping toolstack has moved on, with the rise of powerful web browsers with fast vector rendering, responsive design for smartphones and tablets, and comprehensive GUI frameworks that elevate regular Javascript. CDRC’s requirements have evolved too, with a desire for map visualisation that includes downloadable snapshots, basic analytical functions and filters, rather than the simple view-only concept of CDRC Maps, and a need to embed the map in stories and dataset records, rather than only sitting standalone.

CDRC Maps has also long been hosted directly at UCL, on a local development server. CDRC is a data research centre not a technology centre and there is a desire for use to our server infrastructure for data primarily. The website has long been the most popular public website for CDRC and also is prone to usage spikes due to mass media often finding that maps are a quick way to illustrate a story – or be the story – compared with raw datasets that are less immediately accessible with media deadlines. It was clear that an external host for the sites itself, and ideally the data that powers the site, would be preferable.

To address this and bring CDRC Maps up to date with the new data platform, the centre commissioned Carto and Geolytix to produce CDRC Mapmaker during late 2020. The developers created a Node.js based website that uses the Vue templating framework. Mapbox GL JS 1 is used for the map controls/canvas and the vector tile rendering. The map framework has recently become non-open but there is an open fork, MapLibre, which we will take a look at in due course. The development toolchain has also been brought up to date with industry practice, with proper source code management, continuous integration, rapid development/testing on localhost, and deployment through GitHub.

Map config is in Javascript but this component is separated from the templating Vue/Javascript allowing configuration and setup of new maps to be discrete from the main code itself.

Data is completely separated from the code and there is no server-side processing element for the code. (We do also use an external service, Google Analytics, for our stats). The data is hosted on Carto’s data platform, where a number of datasets are loaded, and also a postcode lookup table. Carto is in fact built on PostgreSQL/PostGIS and provides a management GUI to allow these to be managed independently of the map code.

While the complete (albiet minified) code, config, fonts, images and stylesheets are less than 4MB, the datasets themselves use approximately 7GB of space on the Carto servers. Each geography used (MSOA, LSOA, OA, local authority) has four spatial data files, representing the unmasked choropleth along with three levels of clipping – urban extent (towns/cities), detailed urban (village level) and individual building blocks.

The application is structured around presenting two types of maps – metric maps (which show a various continuous variables associated with a particular dataset, sliced into groups) and classification maps which categorise areas into a single value (sometimes with a hierarchy of levels) and generally include a pen portrait description of the category.

We were delivered six functioning maps and I have gradually worked on extending the codebase and GUI functionality to encompass the wider variety of maps that were on CDRC Maps and that are listed in CDRC Data. Quirks of each additional map have actually meant minor changes to the code in each case to accommodate them, but I am hopeful now that the codebase is broad enough to allow for additional maps to be added in the future with minimal effort.

For this first release of Mapmaker, there are around 30 maps, covering CDRC classifications such as Consumer Vulnerability and the Internet User Classification (IUC), CDRC metric products such as Access to Healthy Assets and Hazards (AHAH) and Residential Mobility (Churn) and some popular government datasets like the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD), VOA building ages and Ofcom broadband speeds/availability.

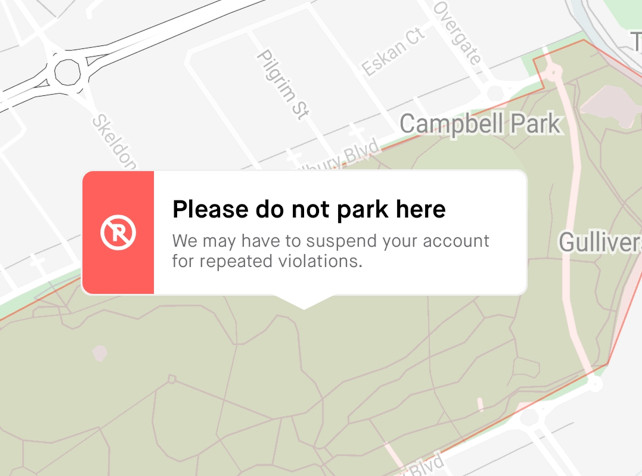

Users can filter maps based on one or more classification categories or on multiple metric value ranges, and a PDF report can be easily produced with a view of the current map, a key and accompanying text and direct link. Clicking many of the maps will not only present the metrics or portrait, but include statistics on proportions in the current administrative area or a custom drawn region. The user interface is deliberately simple with standard pan/zoom controls, map selector, postcode search and layer toggles – that’s it. Planned development in the short term will include an even simpler UI to allow for easily embedding the map in CDRC Data and other CDRC data-led outputs.

CDRC Maps is currently still available for the limited number of maps that show datasets not included on CDRC Data, and it does have the advantage of a pure raster display meaning that some of our controlled datasets which require limited dissemination can be included in this way – on CDRC Mapmaker we would be delivering the dataset to the user’s browser, which is not ideal. Our plan is to de-brand CDRC Maps to provide a home, outside of the core CDRC output, for these legacy maps, in the same way that we have a GitHub repository storing some of our older datasets no longer on our main sites. CDRC is now nearly 8 years old and as the centre’s focus has been refined, not all our older assets have remained central to its mission, but for research reproducibility and historic linking purposes, it is important to preserve these.

We hope CDRC Mapmaker forms a useful visualisation tool for some of CDRC’s many data assets, and its filtering and reporting functionality allow CDRC’s data to be viewed and used in new ways.