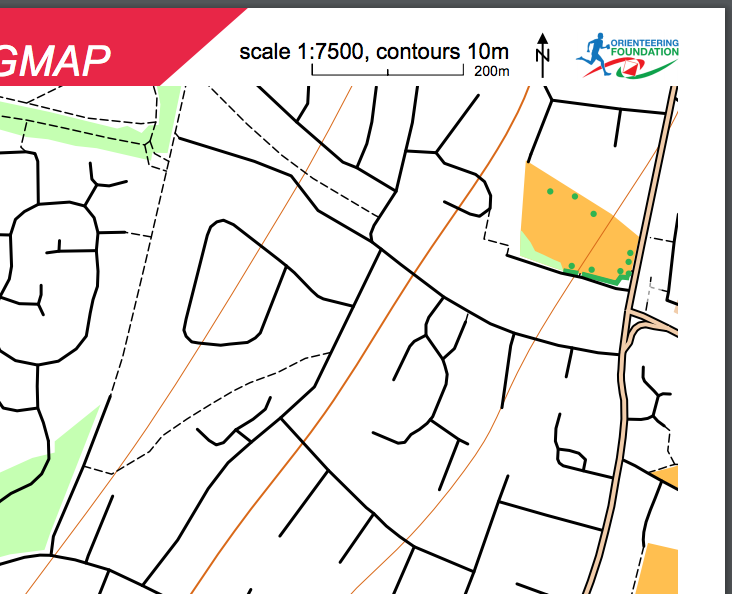

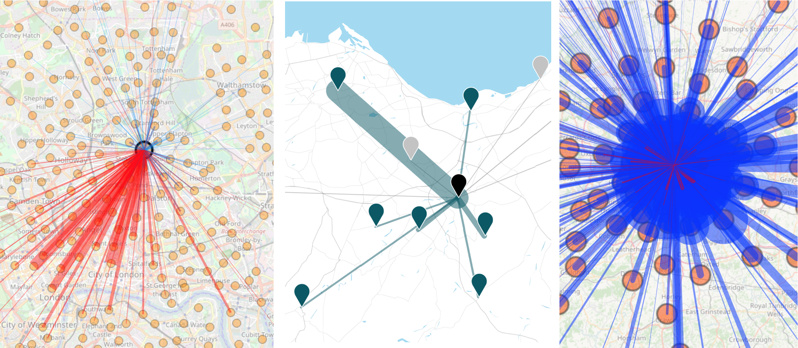

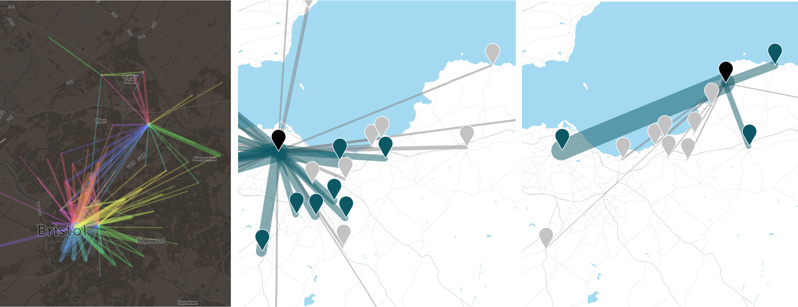

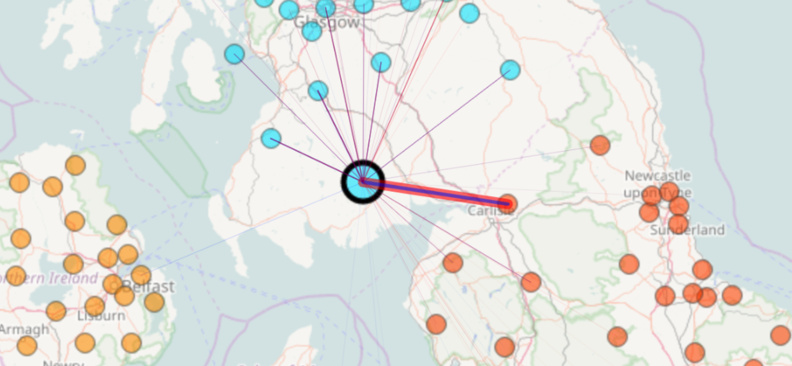

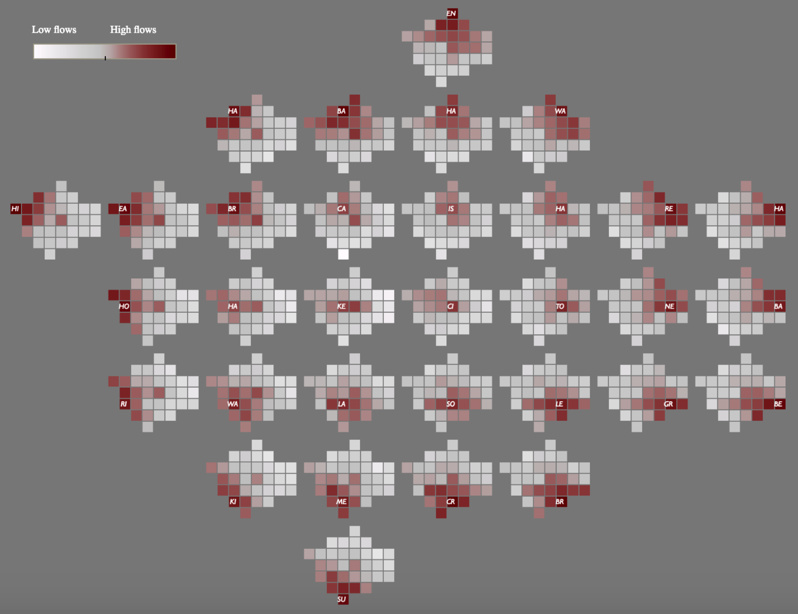

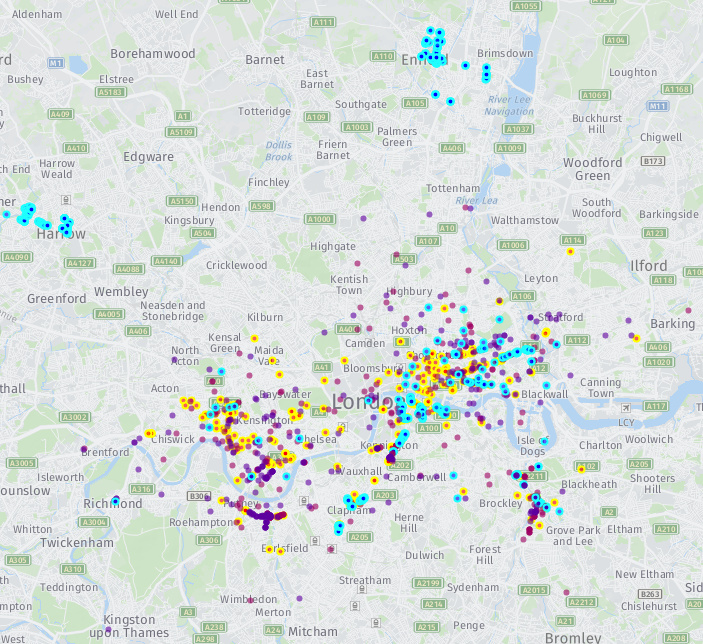

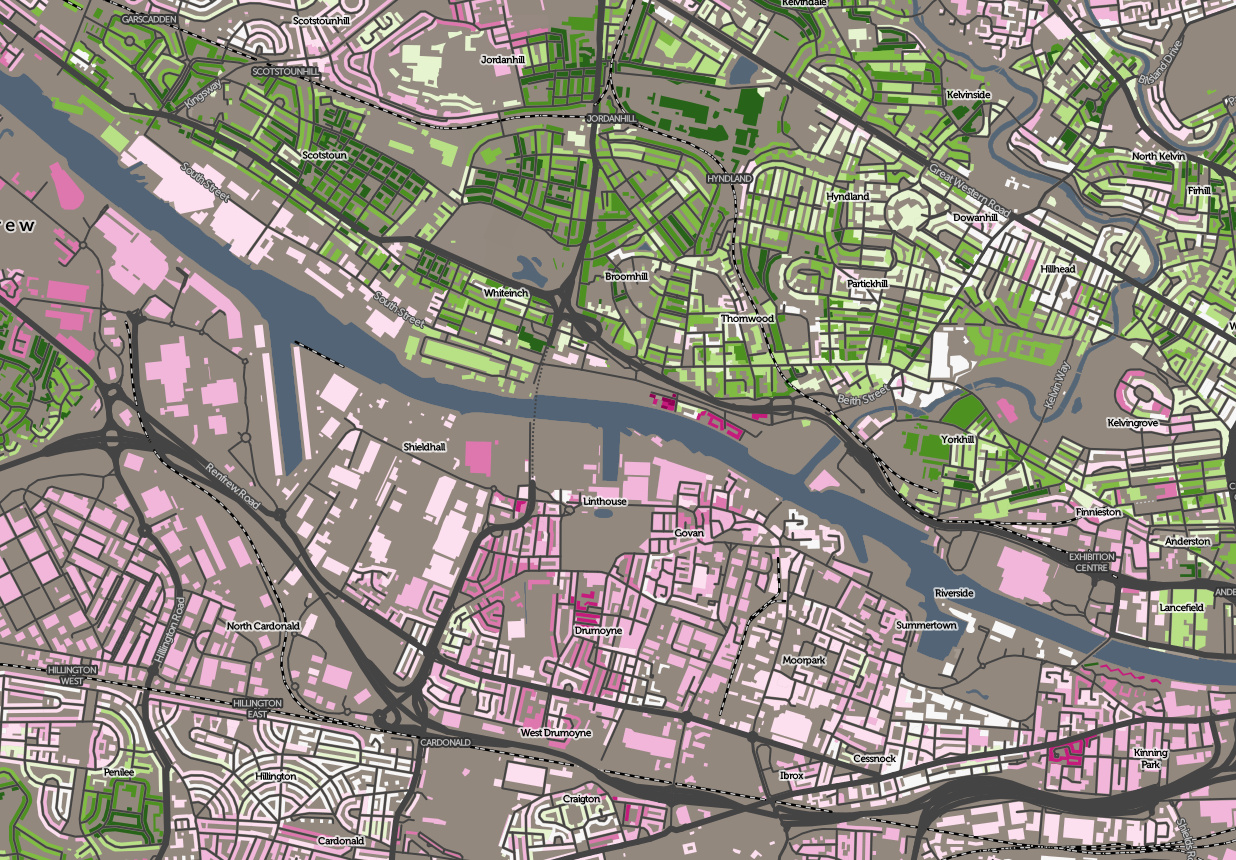

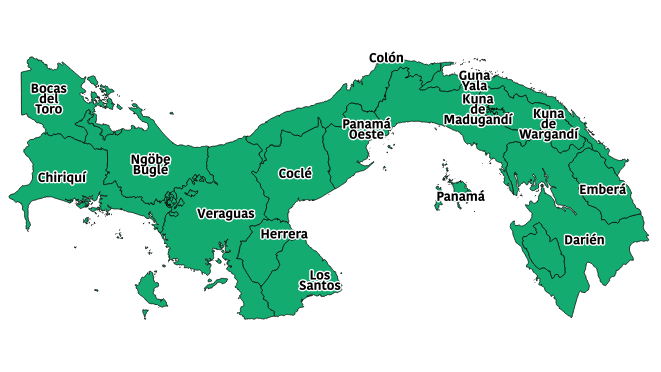

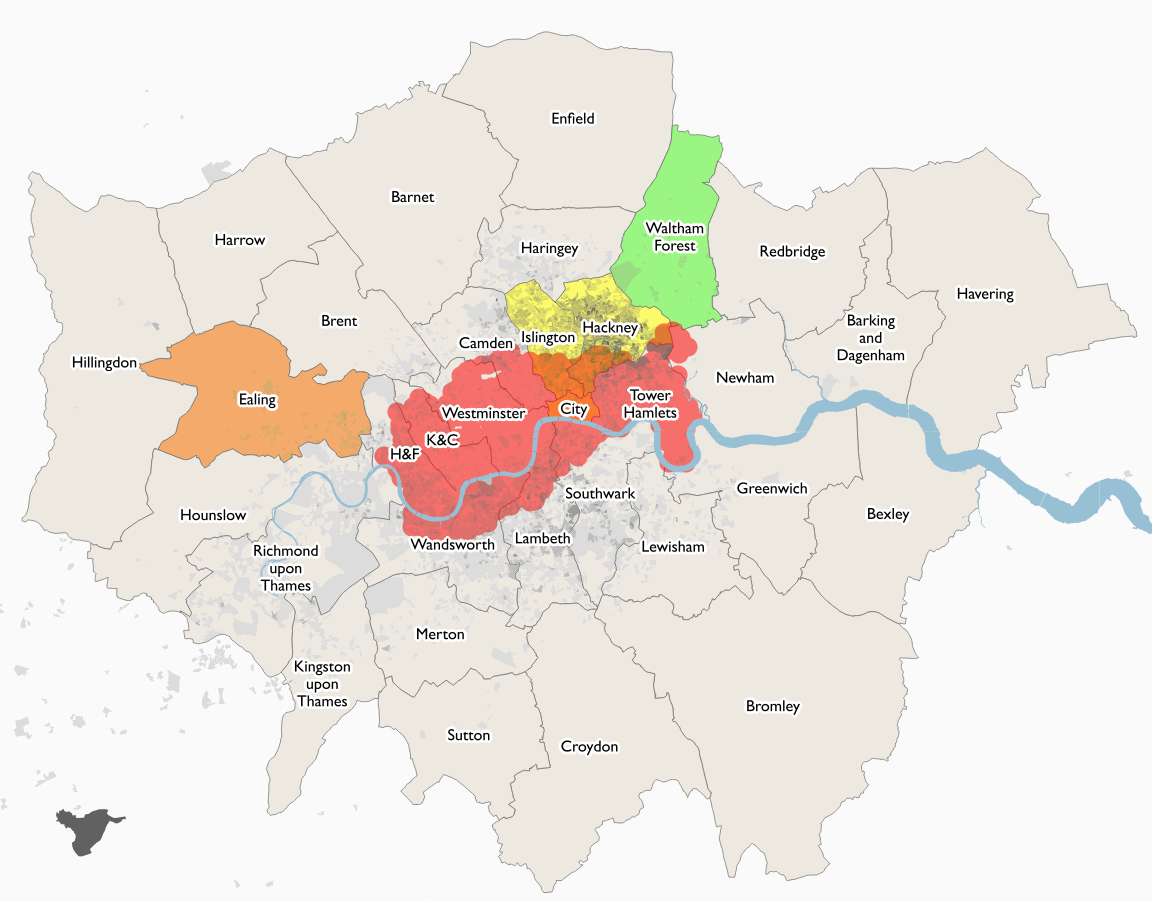

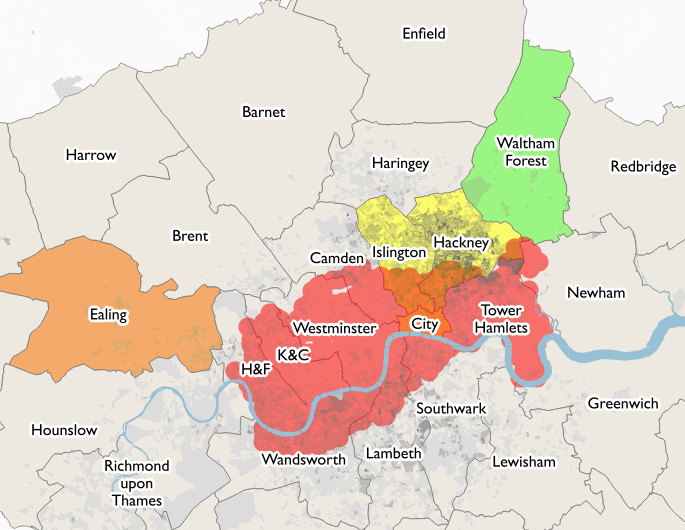

Bikeshare system coverage in London, November 2017. Shading: Proportion of people who cycle to work.

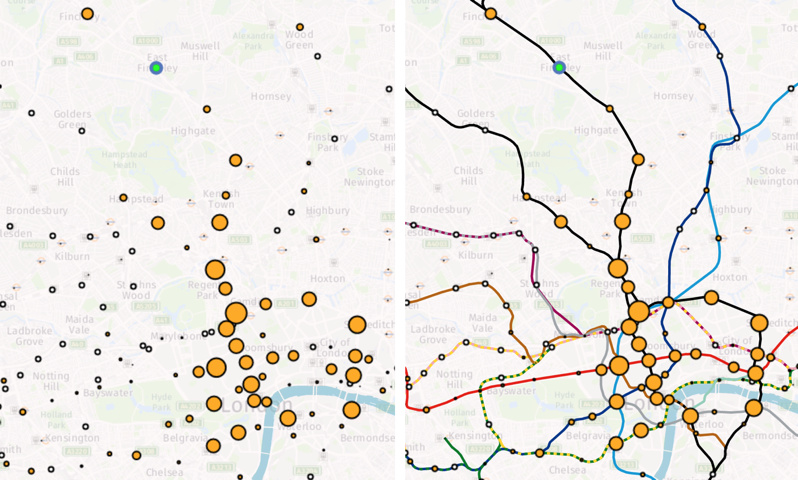

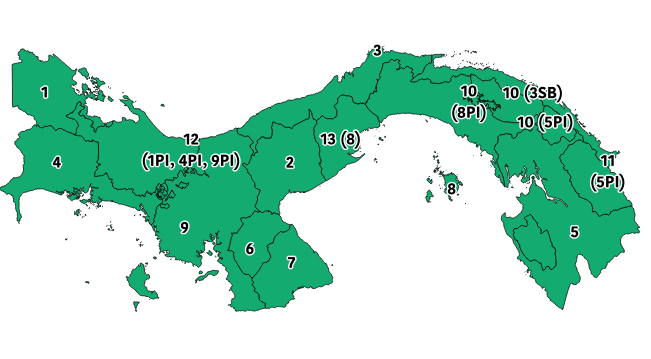

Updated map showing bikeshare system coverage in London, June 2018

There are now five bikeshare systems operating in London:

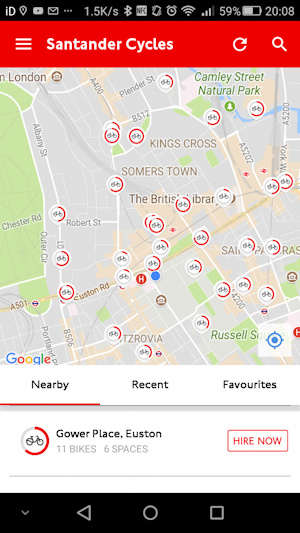

Santander Cycles (Central London)

Photo: Copyright TfL.

Photo: Copyright TfL.

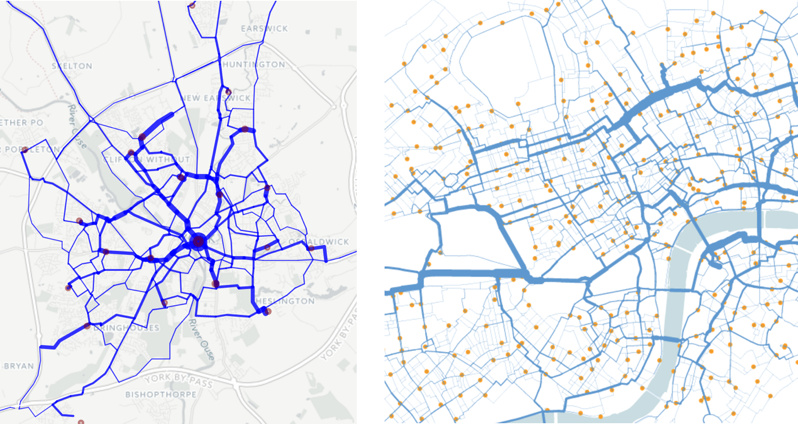

Santander Cycles are red, they launched in July 2010 and currently have 9500 bikes on the street (around 12000 in total), covering an area of 110km across 11 boroughs and the City of London – this sounds impressive, but it is only 7% of London’s area (based on a 500m station buffer), and equates one bike for every 950 people in the capital. You can see the live state of the system (in terms of empty/full docking stations) on Bike Share Map. As a publically funded system, Santander Cycles have an excellent open data policy and release live docking station data which can be readily mapped, location information and historic journeys through TfL’s Open Data Portal.

Santander Cycles last week unveiled their “50000-series” bikes which are part-manufactured in the UK, with smaller wheels, bluetooth asset tags and a number of other enhancements, although in technology terms they still very much third-generation bikeshare bikes (“dumb” bike, smart dock) and the system remains expensive to use with a complicated pricing structure (£90/year or £2/day membership for journeys under half-hour, £2 per extra half-hour), with any expansion hamstrung by the very expensive docking station installation costs – so its footprint has only slightly expanded in the last few years. There have been some other innovations, such as widespread use of Blaze laserlights, and its current sponsor has also invested considerably in promoting the system. The Santander Cycles system looks expensive and rigid, particularly compared with the newer alternatives. It is, however, in terms of bike quality, maintenance and use, and public acceptance, the “gold standard” of bikeshare in London.

Santander Cycles last week unveiled their “50000-series” bikes which are part-manufactured in the UK, with smaller wheels, bluetooth asset tags and a number of other enhancements, although in technology terms they still very much third-generation bikeshare bikes (“dumb” bike, smart dock) and the system remains expensive to use with a complicated pricing structure (£90/year or £2/day membership for journeys under half-hour, £2 per extra half-hour), with any expansion hamstrung by the very expensive docking station installation costs – so its footprint has only slightly expanded in the last few years. There have been some other innovations, such as widespread use of Blaze laserlights, and its current sponsor has also invested considerably in promoting the system. The Santander Cycles system looks expensive and rigid, particularly compared with the newer alternatives. It is, however, in terms of bike quality, maintenance and use, and public acceptance, the “gold standard” of bikeshare in London.

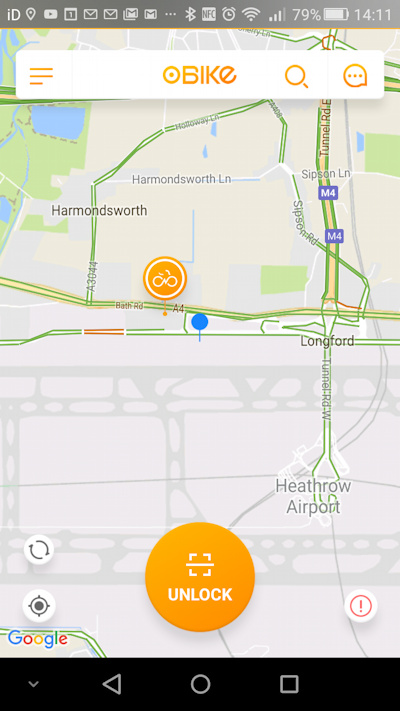

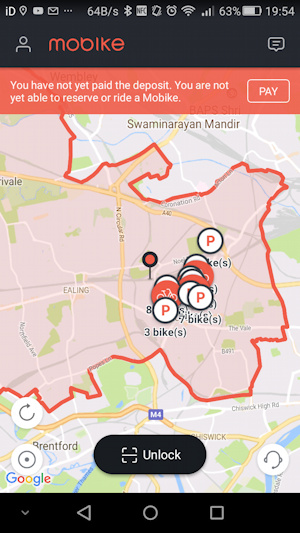

Mobike (LB Ealing)

Mobike (orange bikes) were the first dockless fourth generation* (smart bike, dumb dock) compliant (working with local authorities) system in London, which launched in Ealing in July this year – a far from obvious place to launch, as Ealing has a very low tradition of cycling in general (no dark areas in the map above). However, Mobike did have UK experience before, having had a bigger and higher-profile launch in two of Greater Manchester boroughs. Mobike persevered through initial bad publicity due to vandalism and can be seen on many streets of the city. Personally, I found Mobike extremely uncomfortable to cycle – their bikes have been shipped from the far east with little customisation, and their frames are designed for the far eastern rather than the European build (Europeans are typically bigger!) At its maximum extended saddle position, it was uncomfortably tiny to pedal one. This is a pity, presumably the extremely cheap mass manufacturing costs of sticking with their global design were too tempting.

The Ealing launch had a reported 750 bicycles although as ever you have to take the numbers with a pinch of salt. A quick look at the app reveals around 160 bikes in the preferred zones and around 10 parked elsewhere. Mobike is very cheap and has a simple to understand pricing model (£29 joining fee then 50p per half-hour ride). One nice touch is that if you have a membership of the Manchester system, it will work fine in London too. Ealing is not a densely populated inner-city borough and the 750 bicycles serve a huge 56 square kilometres – in practice, as shown on the app map, the bikes (and zones, shown with a “P”) are clustered in the eastern edge of the borough, around Acton. I wish Mobike good luck but they need more comfortable bikes and to get into a borough with an established cycling tradition, and operate around a larger area than the few square miles in the eastern end of this borough. Mobike, as a fully commercial operation, does not release bikeshare open data for Ealing (dockless bikeshare data does have theoretically considerable economic value), although they have plans to release it for Manchester (likely a stipulation from the local authority there) so maybe it will come here too in time.

The Ealing launch had a reported 750 bicycles although as ever you have to take the numbers with a pinch of salt. A quick look at the app reveals around 160 bikes in the preferred zones and around 10 parked elsewhere. Mobike is very cheap and has a simple to understand pricing model (£29 joining fee then 50p per half-hour ride). One nice touch is that if you have a membership of the Manchester system, it will work fine in London too. Ealing is not a densely populated inner-city borough and the 750 bicycles serve a huge 56 square kilometres – in practice, as shown on the app map, the bikes (and zones, shown with a “P”) are clustered in the eastern edge of the borough, around Acton. I wish Mobike good luck but they need more comfortable bikes and to get into a borough with an established cycling tradition, and operate around a larger area than the few square miles in the eastern end of this borough. Mobike, as a fully commercial operation, does not release bikeshare open data for Ealing (dockless bikeshare data does have theoretically considerable economic value), although they have plans to release it for Manchester (likely a stipulation from the local authority there) so maybe it will come here too in time.

Ofo (LB Hackney, LB Islington and City)

Ofo (yellow bikes) are, like Mobike, a big global player in dockless fourth generation bikeshare. They launched in Hackney – London’s spiritual home of regular cycling – in September, and have just announced (this week) an expansion to the neighbouring borough of Islington and the City of London, meaning serious commute potential of these bikes.

I have ridden an Ofo bike (a one-off in Manchester) and found it extremely comfortable – it felt like riding a “real” bike rather than an approximation of one. Like Mobike, Ofo have a low joining fee, a flat rate for usage and the membership can be used in their other systems (including Cambridge in the UK). Ofo has targetted boroughs with a good cycling tradition and also is, in some parts of the boroughs, in direct competition with the incumbent Santander Cycles – the only one to do so (see map below). Hopefully this competition will lead to innovations on both sides and not damage either.

I have ridden an Ofo bike (a one-off in Manchester) and found it extremely comfortable – it felt like riding a “real” bike rather than an approximation of one. Like Mobike, Ofo have a low joining fee, a flat rate for usage and the membership can be used in their other systems (including Cambridge in the UK). Ofo has targetted boroughs with a good cycling tradition and also is, in some parts of the boroughs, in direct competition with the incumbent Santander Cycles – the only one to do so (see map below). Hopefully this competition will lead to innovations on both sides and not damage either.

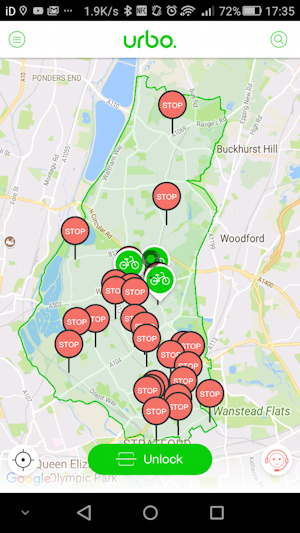

Urbo (LB Waltham Forest)

Photo: Paul Gasson on Twitter.

Photo: Paul Gasson on Twitter.

Urbo (green bikes) are another dockless fourth generation bikeshare operator. They are an Irish company, although they are buying the bikes and technology (e.g. the smart lock and the apps) from China and customising locally. Their bikes are the most attractive of the new dockless bikeshare bikes I have seen (with a nice curve design on the frame) and appear (I haven’t ridden one yet) to be similar in overall build style, and so hopefully comfort, to Ofo’s bikes. Waltham Forest (39 sqkm in east London with some tradition of cycling, on its western edge) is their first system and it has only just launched this week. They also do not yet release open data (although they have only just launched). Ofo may be most useful for residents of Higham Hill, Poets Corner, the top of Walthamstow Village and certain other parts of the borough to get quickly to the stations on the efficient Victoria Line or Overground to central London.

Like Ofo and Mobike, Urbo have designated zones in their host boroughs and induce users (via cheaper journeys) to end their journeys in these zones (shown with the STOP icon on their app’s map, here). These zones come with a bespoke street sign erected by the local authority, as well as the usual taped/painted markings on the ground. It is a little surprising that Waltham Forest have included the operator logo on the signs (presumably to Urbo’s delight) as there is no good reason why other dockless systems, when they inevitably arrive here too, should use these spaces too. It is kind of like the council painting new car parking spaces on a street and putting up a sign, with the Ford logo, saying they are spaces for Ford cars only. They are just spaces on a road/pavement…

Like Ofo and Mobike, Urbo have designated zones in their host boroughs and induce users (via cheaper journeys) to end their journeys in these zones (shown with the STOP icon on their app’s map, here). These zones come with a bespoke street sign erected by the local authority, as well as the usual taped/painted markings on the ground. It is a little surprising that Waltham Forest have included the operator logo on the signs (presumably to Urbo’s delight) as there is no good reason why other dockless systems, when they inevitably arrive here too, should use these spaces too. It is kind of like the council painting new car parking spaces on a street and putting up a sign, with the Ford logo, saying they are spaces for Ford cars only. They are just spaces on a road/pavement…

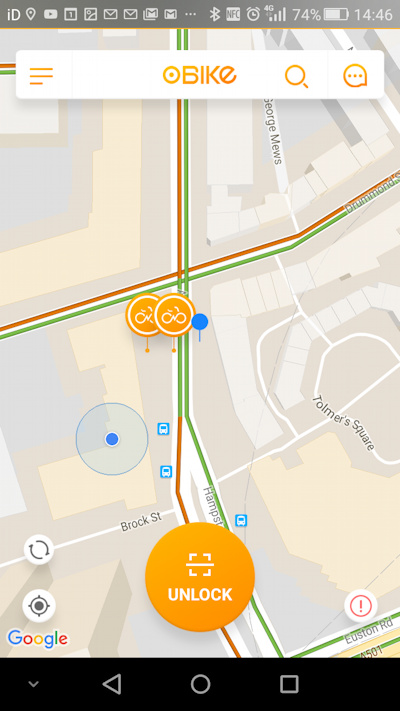

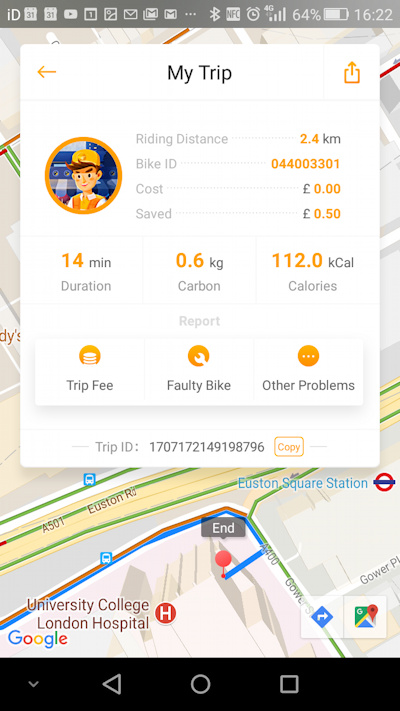

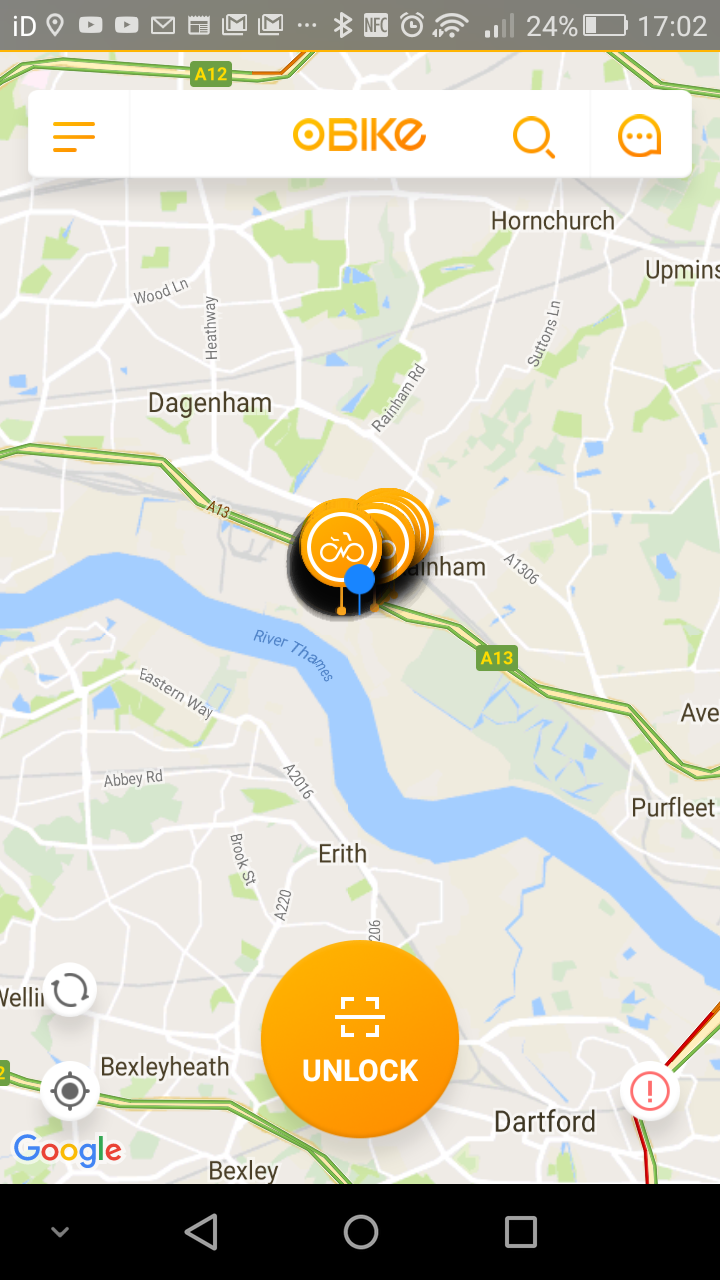

oBike (Withdrawn)

Then there’s oBike (orangey-yellow) which launched in July without coordinating with boroughs (using the Uber-style “forgiveness is easier than permission” modal), had a number of its bikes impounded by Wandsworth borough and withdrew from the capital – almost all of its bikes are lurking behind locked gates in an industrial park in Rainham so they aren’t included on the maps here. There is the odd one that got away from the purge and remains in central London. They will return, I’m sure, once the company has a strategy for compliance with TfL and the boroughs. oBike did at least wake up authorities to the fourth generation revolution, and force some much-needed policy documents to be hastily released. I rode a few oBikes and found them more comfortable than the Mobike but not as good as Ofo, Urbo or Santander Cycles.

November 3rd Snapshot

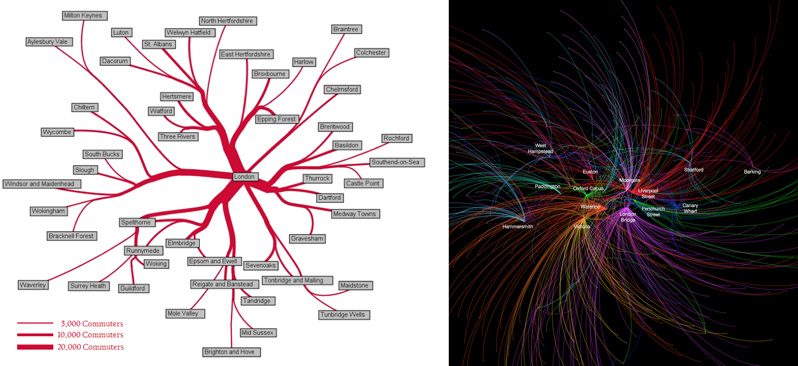

| System | Type | Locations | Area /km2 |

Launch Date |

Reported Bikes** |

Available Bikes (Estimates) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Santander Cycles |

Dock -based |

Central London | 110 | July 2010 | 12000 | Was 10800 now 9600*** |

| oBike | Pure dockless |

All London, but withdrawn |

1570 | July 2017 | 400 initially 5500 planned |

Was 1500 now 6 |

| Mobike | Zoned dockless |

West: Ealing | 56 | July 2017 | 750 | 160 |

| Ofo | Incentive dockless |

North: Hackney, Islington & City |

37 | Sept 2017 | 300-400 | Around 200 |

| Urbo | Zoned dockless |

East: Waltham Forest |

39 | Nov 2017 | 250 | 40 (so far) |

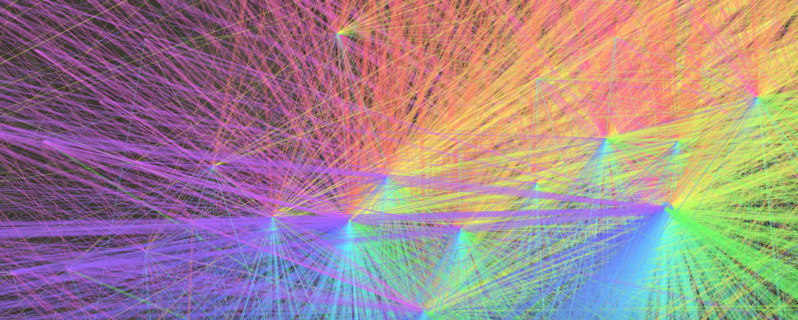

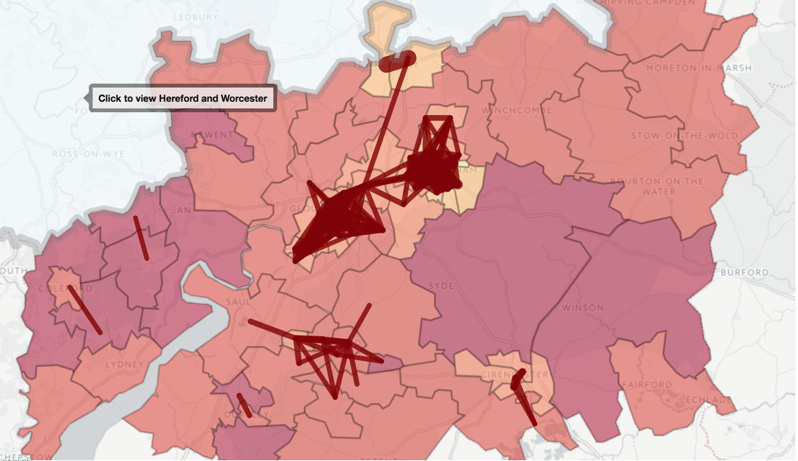

Of course, it’s hard to know how well these systems are being used, particularly as dockless systems don’t generally release this information (except if the numbers are particularly good, as occasional press releases). Santander Cycles reliably gets around 20000-40000 usages a day (i.e. 2-4 usages/bike/day), and certainly, on the more central parts of the Cycle Superhighways during rush hour, there is a sea of red Santander Cycles amongst the other cyclists. Anecdotally, I’ve a couple of Ofo bikes in use, but this is a bit unfair on Ofo and Urbo – I regularly cycle through Hackney on my own bike, but don’t generally pass Waltham Forest and Ealing. My sneaking suspicion is that Ofo will do quite well, by targeting the boroughs where there are going to be a lot of cyclists, and that Mobike and Urbo will either have to expand or will stay irrelevant in London’s overall cycling picture. This sounds harsh, but, as DataShine Region Commute and TubeHeartbeat show, Londoners move beyond their borough boundaries a lot. We shall see, we live in interesting times for bikeshare.

This map (an inset of the map above) shows the reach of the four systems (excluding oBike) in London. The shading behind shows the proportion of residents there who cycle to work (2011 Census data, Copyright ONS) and therefore likely enjoy good cycle infrastructure and community (e.g. cycle cafes, cycle repair workshops) that would help integrate bikeshare. Parts of Southwark and Lambeth look woefully underserved.

* The first generation of bikeshare systems were free bikes, left on streets for people to use. Inevitably they were stolen or broken. Second generation bikeshare systems used “dumb docking stations” where cash was used to release them. Users were therefore only out by the cash amount if they didn’t release them, and operators didn’t know where they were without visiting the docks, so again they got stolen and/or broken. Third generation bikeshare systems require the user to use credit cards (and so charge a large amount for non-return) and use smart docking stations which can report the status of themselves and their bikes. They have been very popular for the last few years, but require a large up-front investment and are very expensive to operate and maintain, so most are publically subsidised. Minor advances to these (such as GPS on some bikes, or integration with transit smart cards) are sometimes termed as fourth generation but are actually really just usability tweaks to fundamentally the same third generation concept. I am terming the new dockless systems, where the bikes know where they are (through an app, or their own communications) as fourth generation. Physical docking stations can still exist on the ground, to manage the bikes or provide a known starting location, but the bikes don’t have to be left there, if inconvenient – the “hybrid” model, as used in Brighton. Zoned dockless systems (Urbo, Mobike) have tapes on the ground as “preferred” docking zones, replacing the physical docks. Incentive dockless systems (Ofo) don’t even have the tapes – just virtual locations that appear in the app). The Pure dockless systems (oBike) don’t even have anything – inevitably resulting in bikes being scattered through an area.

** These numbers, reported in media and press releases, will invariably be higher that the “available bikes” currently on the streets (or visible in the app, in the case of the dockless systems). The difference can typically be explained by bikes will be in repair or reported broken, some will be in active use (although generally I try to measure at night to avoid this) or in redistribution, some will be in the warehouse, ready to come out in the near future. Ultimately though, if the bikes aren’t available for use, then they aren’t really any good to anyone, so bikes on streets is the number the operators should be reporting!

*** For larger, commuter heavy systems (like Santander Cycles) that are dock-based, there are good operational reasons to slightly reduce the numbers of bikes available during the winter months (where the commuter mode share will be higher) as the flows are more undirectional and therefore full-dock pressures are otherwise worse. In the summer, tourist use acts as a natural rebalancer.