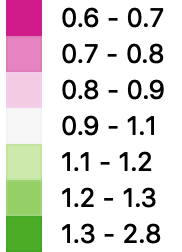

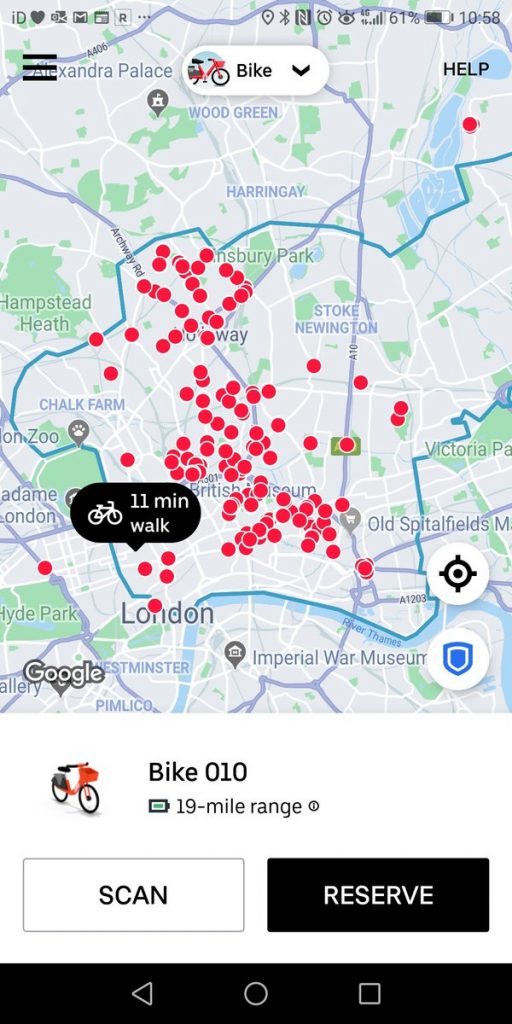

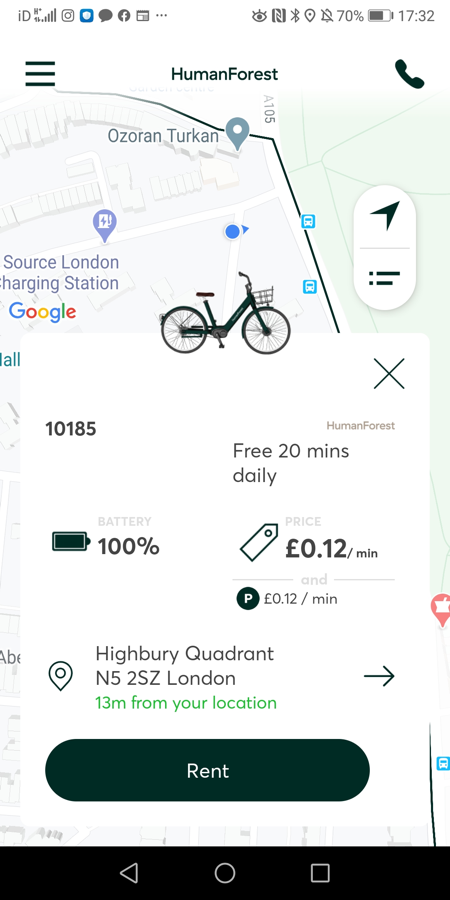

There’s a new bikeshare in London – HumanForest launched yesterday (Wednesday 24 June 2020) with 63 pedelec bicycles. They are planning on rolling out up to 200 bicycles in their Islington trial operation, before hopefully expanding to central London later this summer with up to 1000 in their fleet.

HumanForest’s technology platform and equipment provider is Wunder Mobility, based in Germany. This is the first UK system using these bicycles, so I was keen to try one out in the wild.

HumanForest’s bikes are painted dark green so are a little harder to spot than the late JUMP bikes, which were luminous red, and may or may not make a return under their new owners Lime soon, or the flureoscent yellow Freebikes. They are rather sleekly built, with the battery well integrated into the frame rather than bulging out of it:

The big selling point of the bikes is their electric capabilities and price point – these are pedelec bikes with a top speed of 15mph (you can pedal faster than that but you won’t have any electric assistance). The bikes are free for your first 20 minutes each day, then 12p/minute thereafter. This is broadly comparable with Freebike’s price offering, and much cheaper than Lime’s £1/start+15p/minute pricing. (London’s Santander Cycles did demo a pedelec version last year but have yet to announce a launch date or pricing.)

HumanForest looks extremely affordable, I presume their plan is that the average user will take their 20 minute free journey to get into town, and then HumanForest will collect £2.40 for the 20 minute equivalent return journey. They should also, if they are able to expand quickly into adjacent boroughs, take advantage of the current huge surge in leisure cycling in London. Such users will typically be much less price sensitive and also likely to use the bikes for a longer time.

The HumanForest bikes ride nicely – as you would hope for brand new. European-designed bikes – with more of a power kick than Lime and Freebike, but not quite as much as JUMP offered. As ever, it’s nice to get across junctions from a standing start quickly, and to get up hills with little effort, but for longer journeys, the only very marginal battery boost above ~10mph will be frustrating.

I had a couple of technical issues – the first bike I tried refused to unlock with a “Get closer to the vehicle” message on my phone app despite being right beside the bike. The second worked fine, but had an issue with the adjustable saddle height clamp – it was a little loose, so I kept sliding down. The seat-posts do however come with a nice indication of which setting is needed, based on your own height (in cm):

Overall though, the build quality is good, the bike feels solid to use and has some nice design elements, including the saddle, which has a nice two-tone colour and a flat top, and a handlebar twist-bell.

In a sign of the times, the baskets are all fitted with a cable lock to which is attached hand sanitizer, and the HumanForest app asks you to check you have applied it before hiring:

HumanForest asks users to take a photo of the bicycle once parked at the end of the journey, this is good practice as it will help users “self police” their parking locations. I parked beside another HumanForest bike which was parked across the pavement on an inside bend – not great:

I moved it to the side of the pavement, but this off the weediest alarm I had ever heard. After three rounds of electric buzzing, all was silent again!

As always with bikeshare in London, HumanForest will live or die based on the vandalism and wear-and-tear rates, and how the operation teams deals with these. It is a small fleet, in one London borough, but there is definitely space for a third pedelec fleet in London, so the best of luck to HumanForest and hopefully we’ll see them expand far and wide.