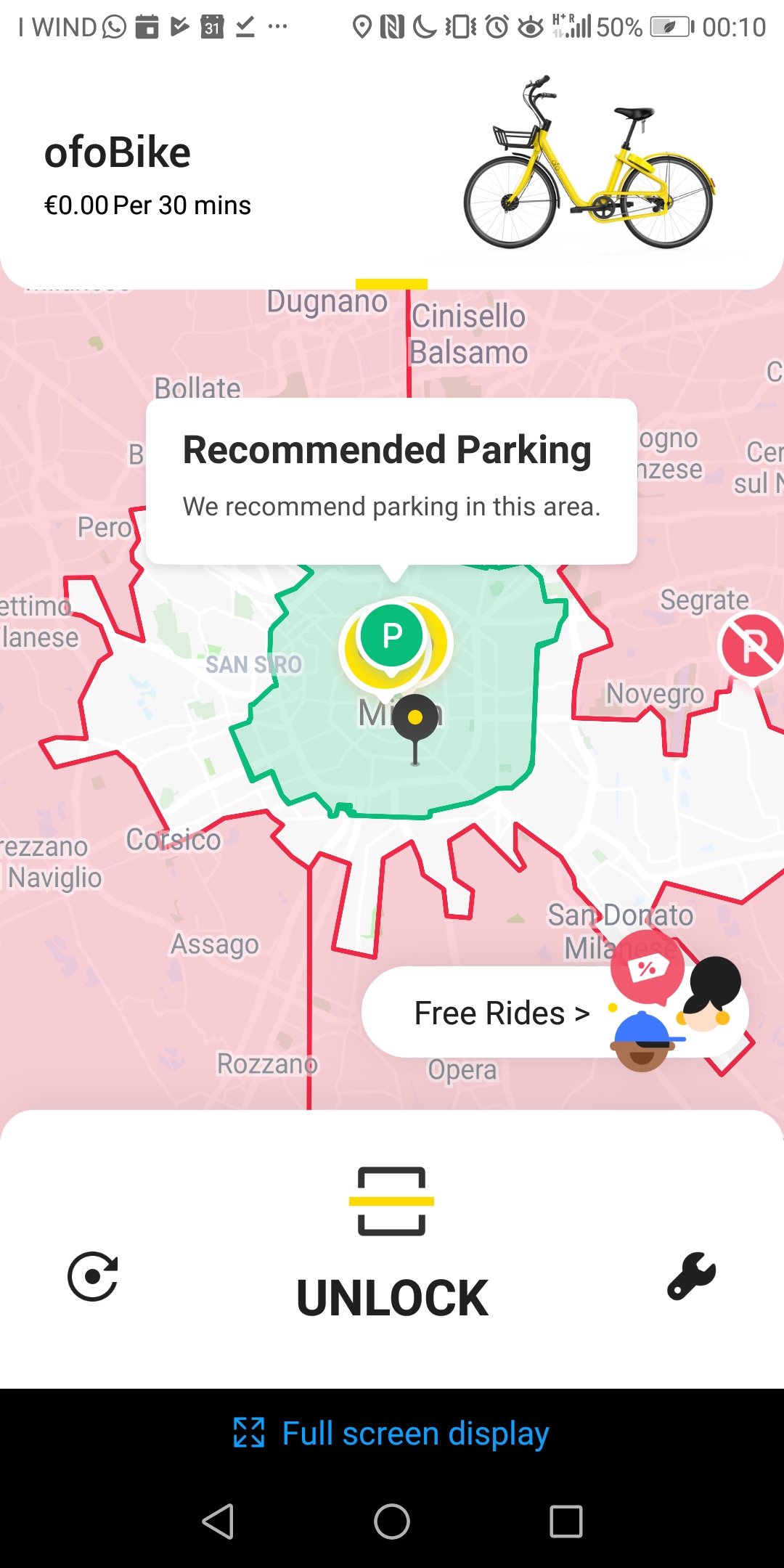

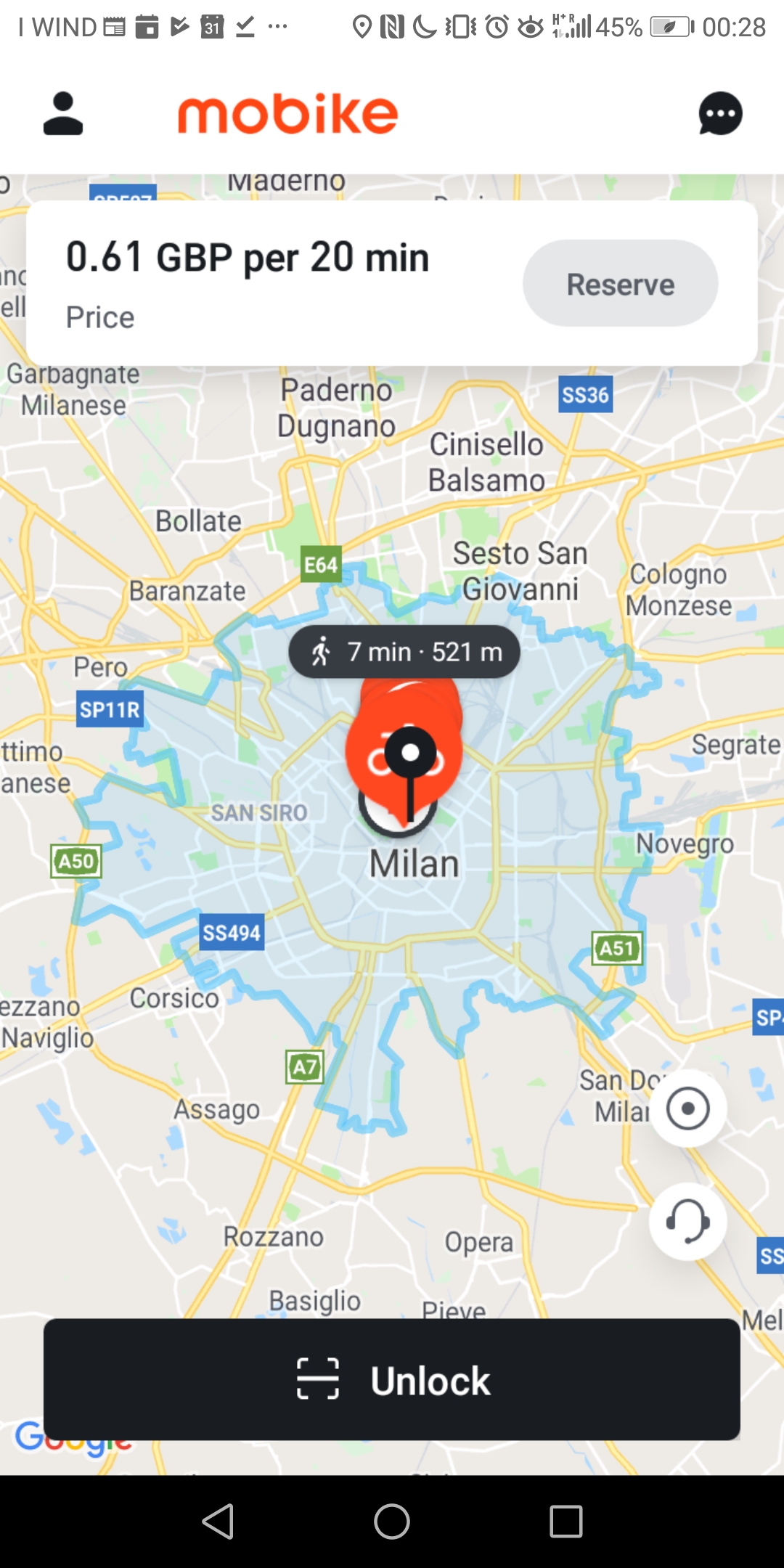

Having travelled to both Milan and Singapore in the last few weeks, it’s worth a note on the bikeshare provisions there.

Milan – BikeMi, Mobike, Ofo

Milan has BikeMi, a long-serving dock-based bikeshare system, which is one of the nearly 400 city systems that I have mapped in Bike Share map. It covers a big part of the city. There was a docking station close to both my hotel and to the location of the the conference I was attending, however far more noticeable were the numbers of Mobikes around the streets. Ofo also operates in Milan, although their bikes are not as prevalent.

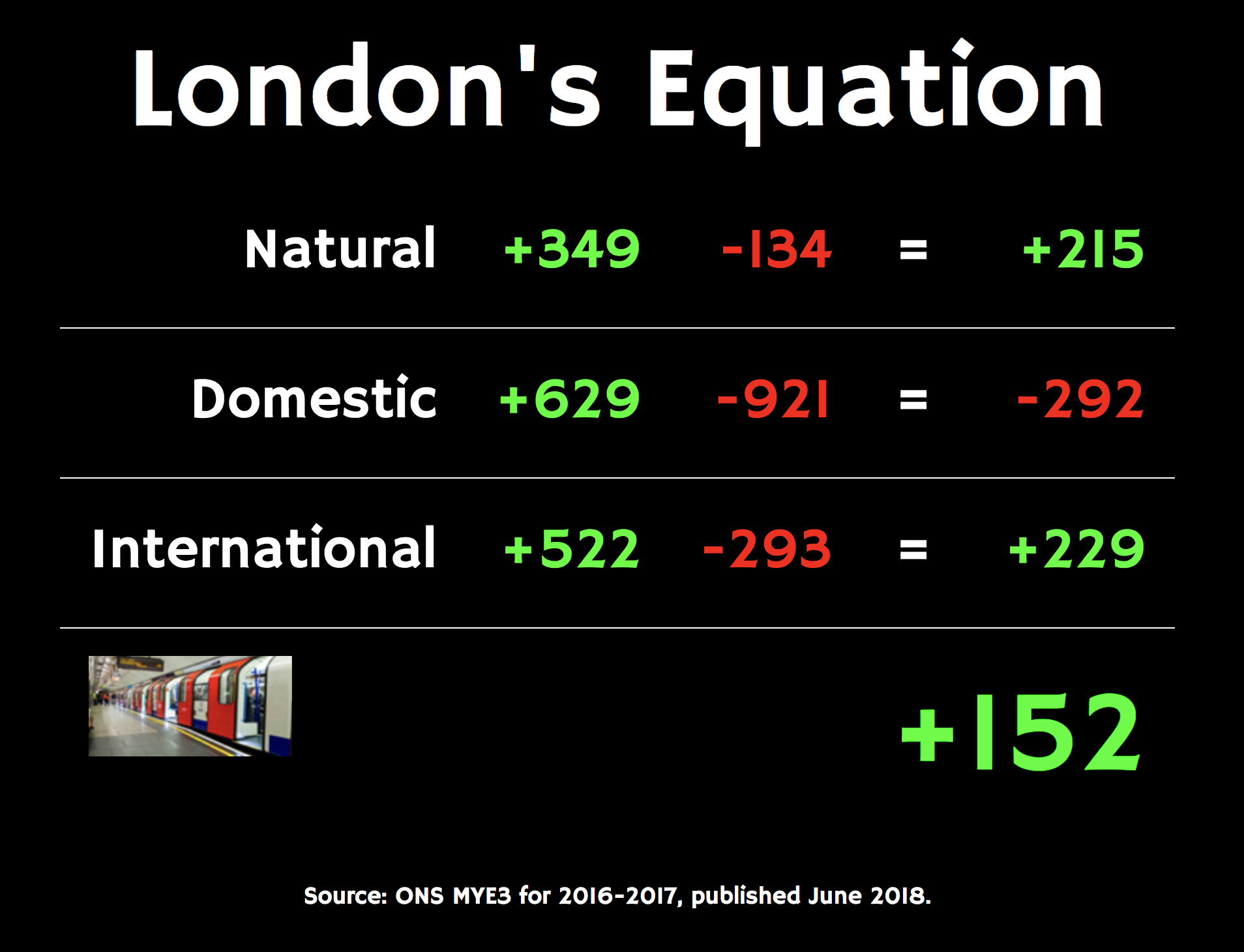

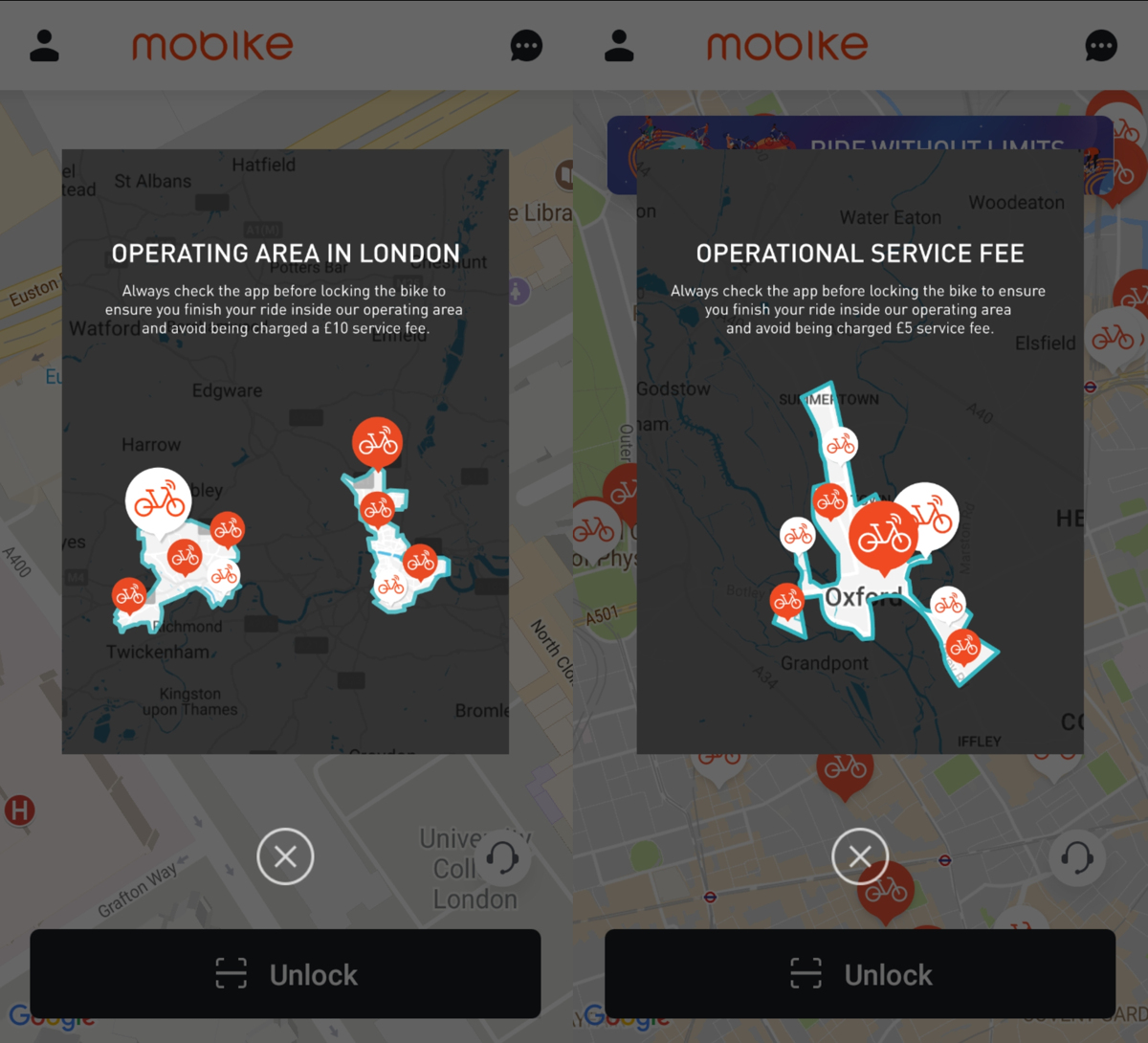

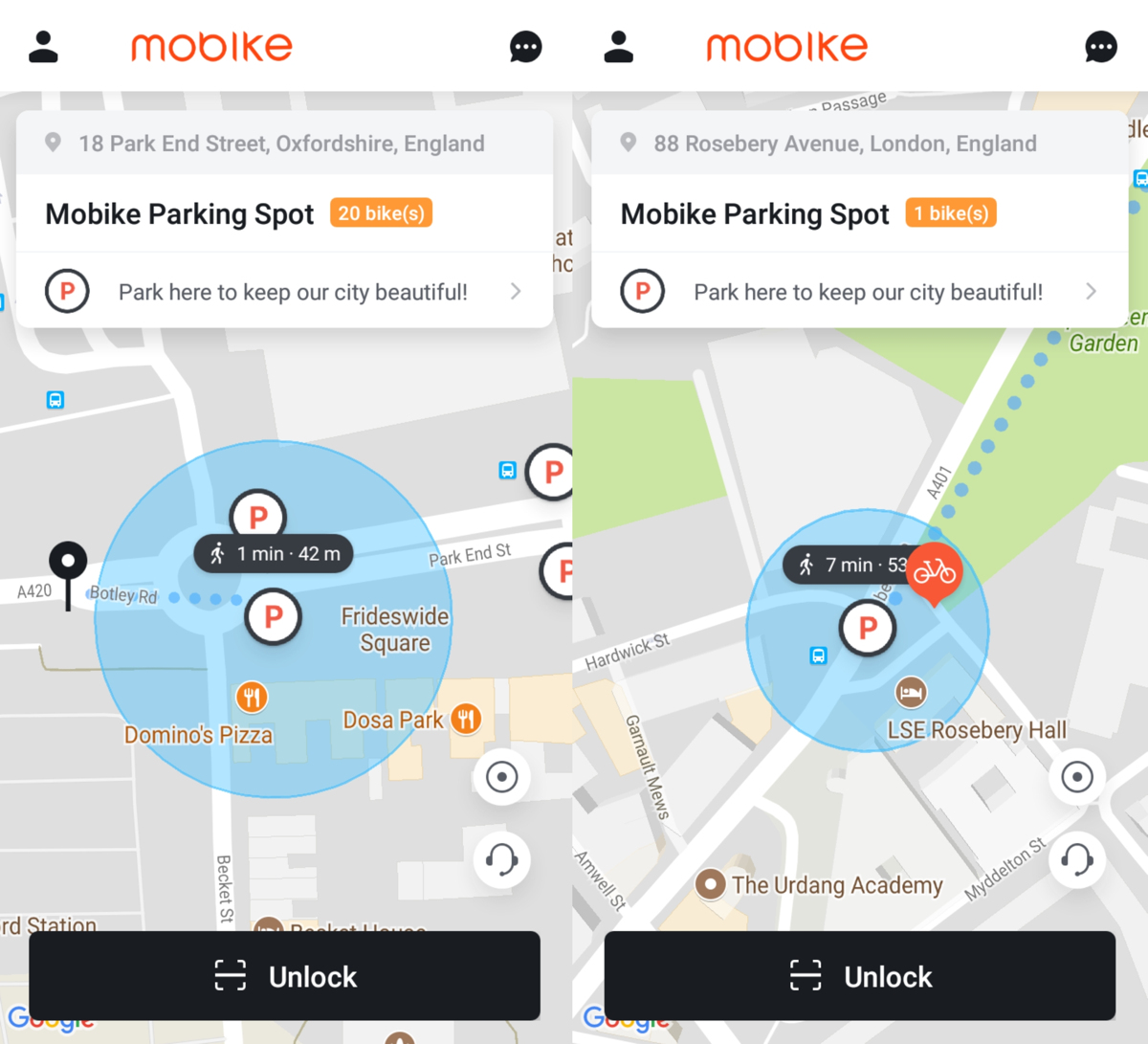

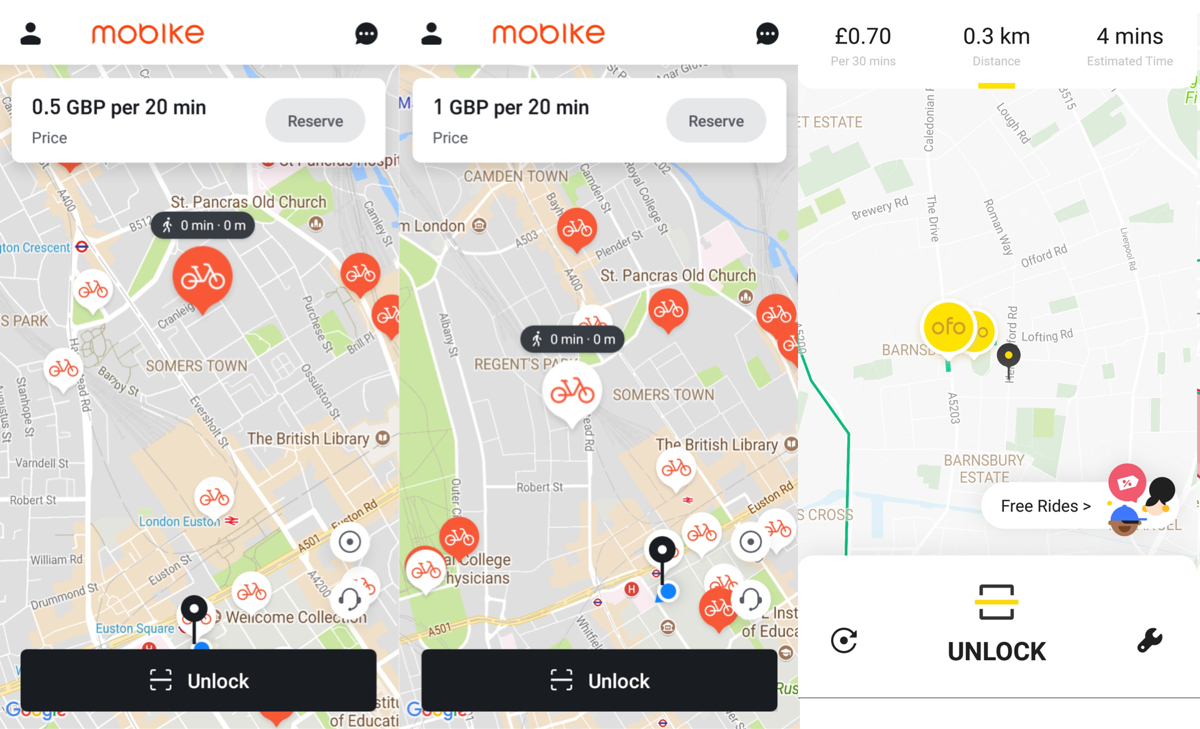

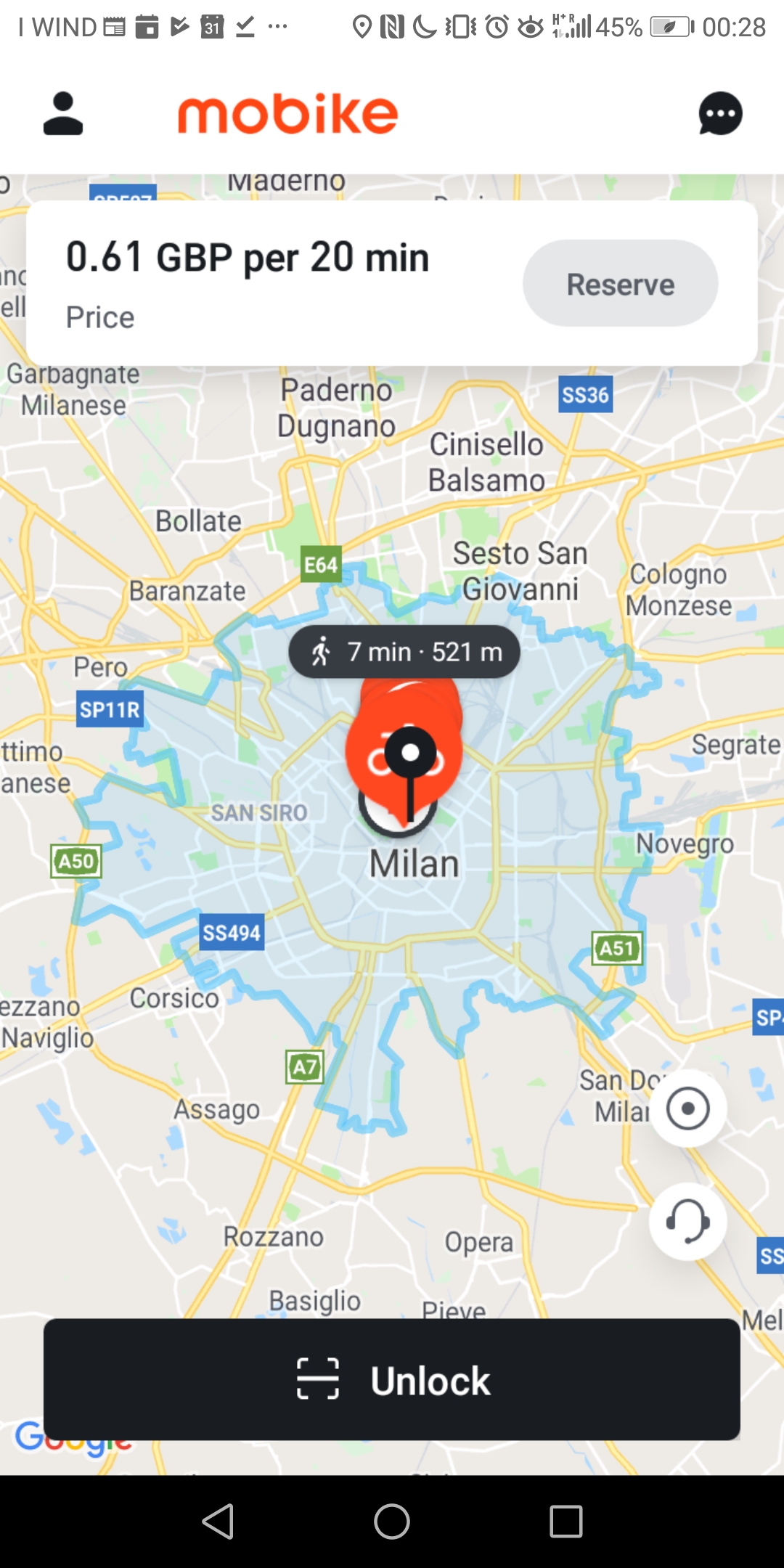

I ended up using Mobike – mainly because I already had the app installed on my smartphone, for my occasional usage in London – and Mobike, like Uber, works nearly seamlessly across the various cities it operates in. This simplicity, combined with the new EU free roaming laws meaning that I can use the app without incurring roaming data charges, and the fact there was one to hire just around the corner, means that Mobike for me won over BikeMi. It’s a problem that dock-based systems are going to struggle with, unless they can somehow collaborate with each other globally. Perhaps a start would be JCDecaux “Cyclocity” systems allowing use across their cities if you are already signed up for another one, and a similar approach for Motivate and Nextbike systems. Although, as each city typically has a monopoly dock-based operator, this approach still has a more limited approach.

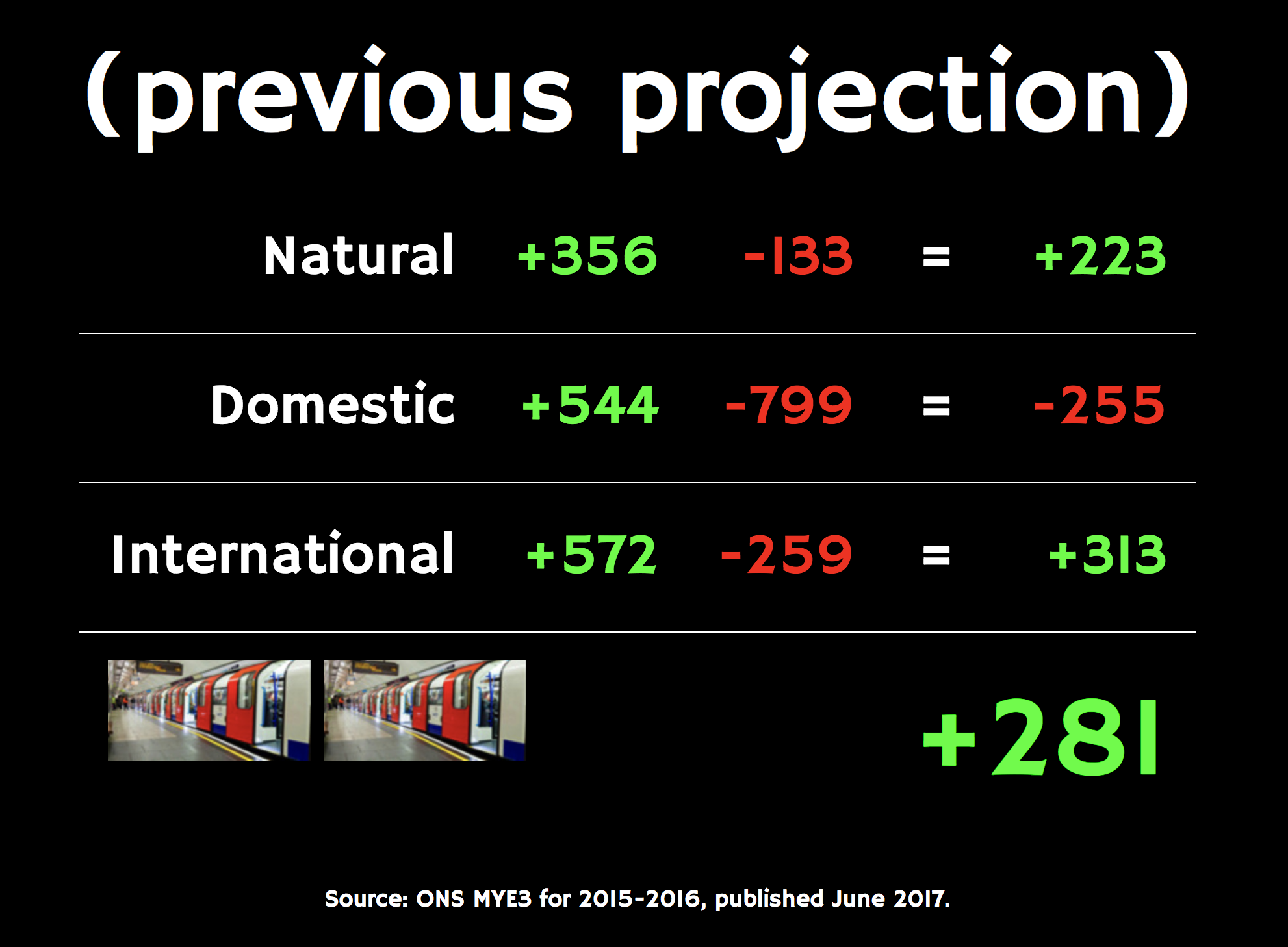

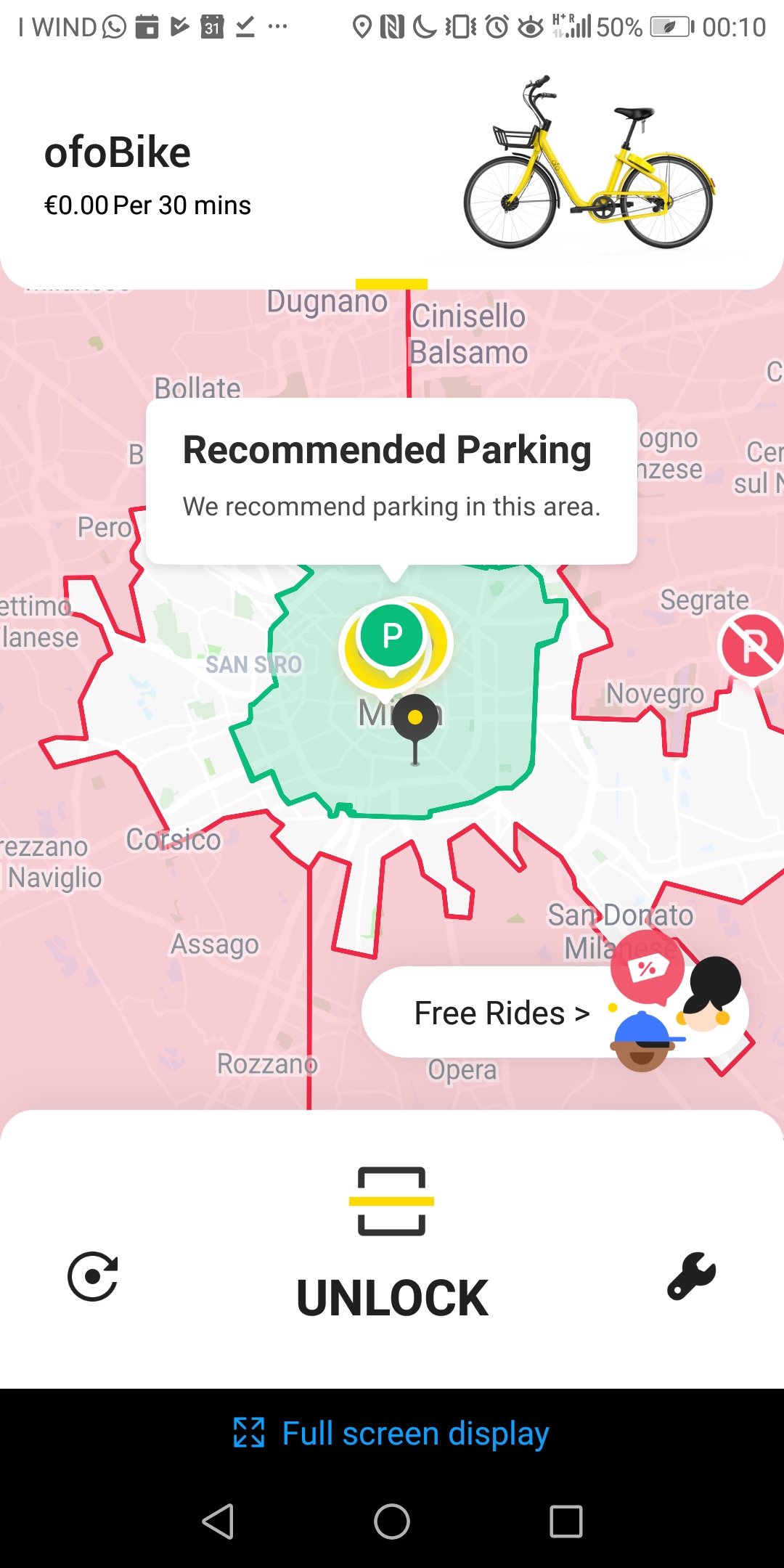

(I say nearly seamlessly – both apps struggle a little initially when moving to a new city. In Mobike’s case, the system boundaries generally don’t appear until the app has been restarted a number of times, after moving to a new city. For Ofo, the pricing indication is initially wrong – I’m pretty sure it’s not free!

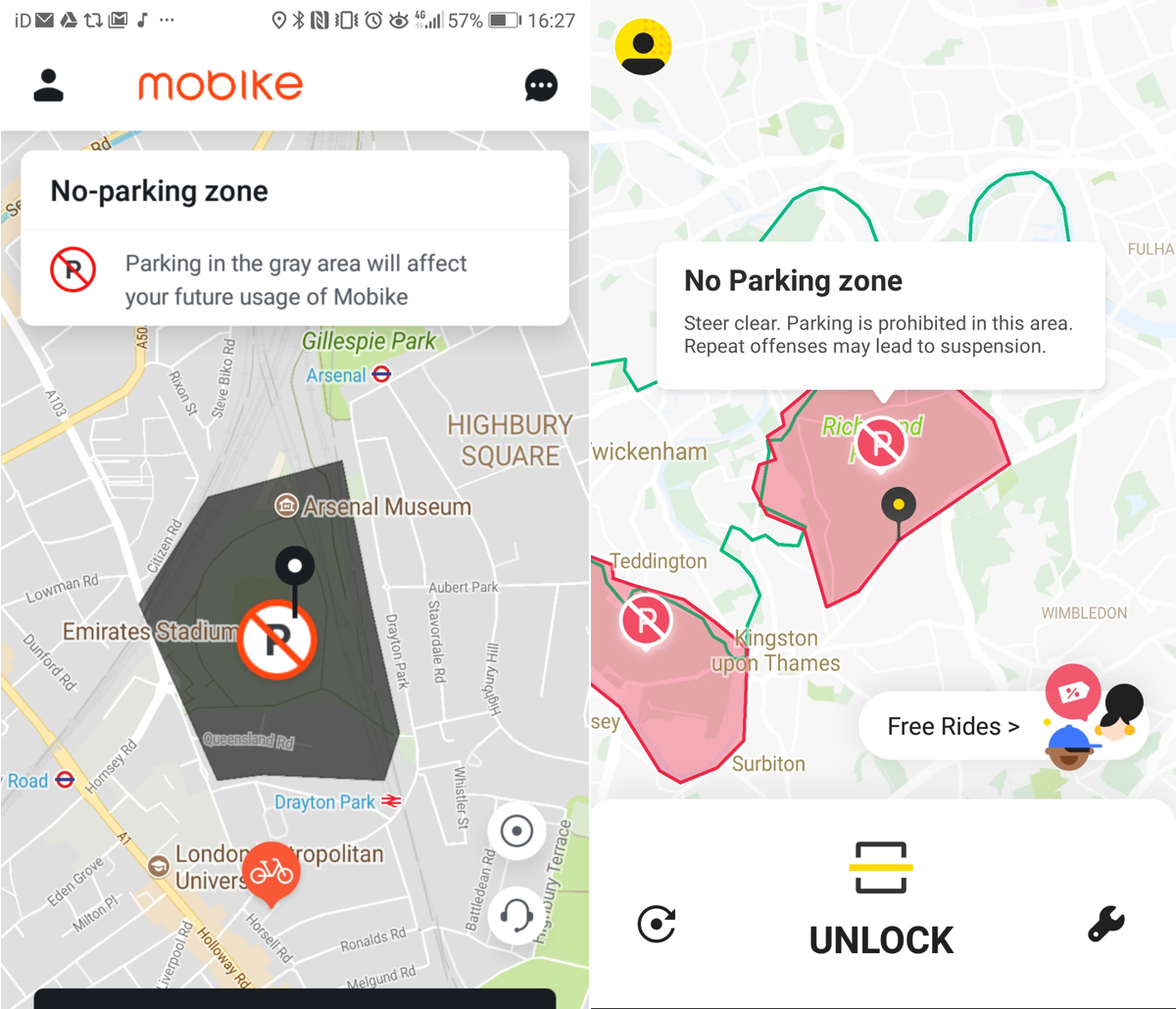

Mobike and Ofo have not suffered in Milan like their have in London. They both operate throughout the historic centre of the city, and much of the suburbs, rather than being artificially constrained on a borough-by-borough basis like in London, or only operating in small sections of the city by operator choice/resource limitations, like in Oxford and Cambridge.

Milan does not have as much in the way of dedicated cycling infrastructure as London, however I generally found a good level of respect from drivers and felt comfortable moving around the city. It was exceptionally hot when I was visiting (35°C) and although I noticed a few other cyclists and also bikeshare users, there weren’t huge nunbers in London. I noticed that most of the Mobikes were single ones which had been left by the previous user, rather than stacked by the operator, and also more than once they had been left in a position entirely blocking the pavement and meaning the pedestrians had to get onto the street to get past. This is a big problem in many cities where dockless operators run systems – how to get users to park responsibilty. The solution – a combination of user attitudes, rules and facilities, is one that does seem to have been solved for the next city I visited…

Singapore – Mobike, Ofo, oBike/GrabCycle, SGBike, GBikes

In Singapore, there is no dock-based system but a wide variety of dockless operators have bikes here – as well as Ofo and Mobike, there are the home-grown SGBike and GBikes (the latter based on the SharingOS system), and OBike (cobranded GrabCycle) – which started out in Singapore. Both GBikes and OBike have ceased in Singapore, presumably their apps no longer unlock their bikes – but they are both scattered everywhere – or rather, this being Singapore, they are neatly stacked up against trees and fences. Will anyone remove the bikes for companies that have ceased to be?

Singaporians being extremely considerate people, I didn’t notice any bikes blocking pavements, or indeed showing any sign of lock tampering or vandalism. A small number of bikes had damaged wheels. Again, I have both the Ofo and Mobike app on my smartphone, but with no free data, and no particular need to cycle, I didn’t hire any bikes this time.

One thing I noticed over and over again is multiple operators bikes, being stacked neatly together. Sometimes, they were located within a painted rectangle indicating an “official” cross-operator permitted parking location:

Other times they were in “dead” pavement areas, such as traffic islands, where no one would otherwise need to be walking or driving:

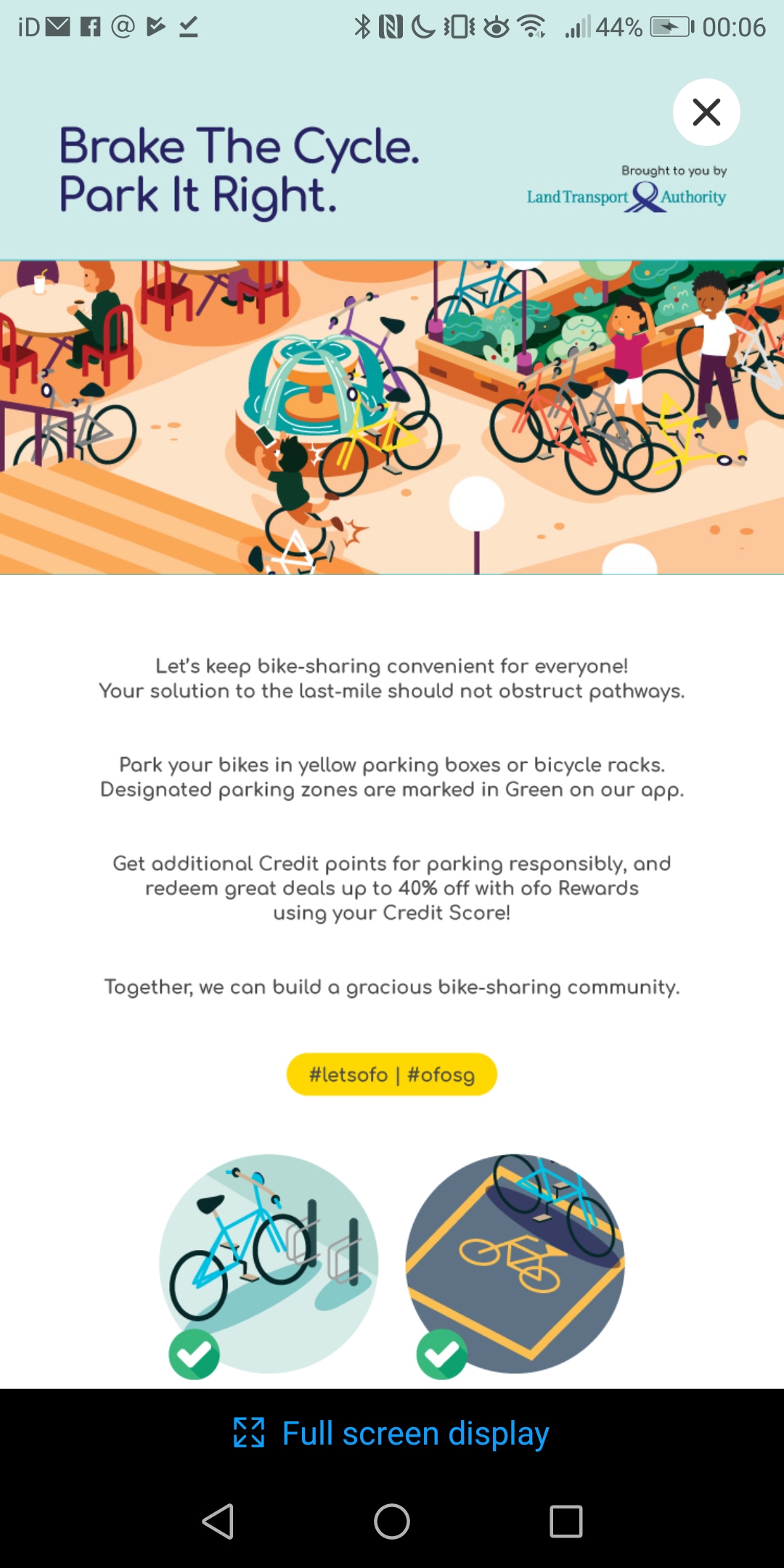

There is clearly some city council direct involvement with the operators – in Ofo’s app, there appears a message from the Land Transport Authority about parking neatly:

(Incidentally, GrabCycle is I believe a multi-operator marketplace/broker. I haven’t seen this before for bikeshare, and Ofo and Mobike are not currently part of it – they are presumably “too big” – but I think ultimately cities with multiple competitive bikeshare operators will likely have to eventually enforce/insist on allowing the bikes to be used through marketplaces. No one wants to have six bikeshare apps installed on their phone, and no city wants six incompatible bikeshare bikes sitting on every street corner, each only useable by a separate dedicated app.)

The central part of the city, at least, is not as bikeable (or walkable) as Milan – with large roads and the lack of much in the way of dedicated cycle lanes, the only cyclists generally seen were on riverside paths and in parks. Pedestrians also can come to junctions without any crossings – except perhaps by a nearby overpass. It’s all very well having a marked parking bay, but if it’s beside a huge road with no cycle lane, is anyone going to use it?

The high temperature (30°C) and humidity, characteristic of the city state throughout the year, doesn’t make it the greatest place for comfortable or leisure cycling. I saw almost no-one using the dockless bikeshare bikes, even through are are loads waiting to be used, but I did see plenty of people on eScooters – both for-hire ones and private ones. It is only a matter of time before these become huge in London.

Intriguingly, there may note be a dock-based bikeshare system in Singapore – but I did notice these bike docks. They are “semi-smart” docks – they have an electronic lock that just locks the front wheel, but they are small and unobtrusive, presumably much easier and cheaper to put in than London’s hard-wired, “street furniture” type docks. They were, here, being used as spaces to keep Ofos, rather than by the bikes they were designed for:

I did notice a number of interesting varients of both Mobikes and Ofos. They have been in the city longer than they have been in the UK, and so a greater number of models are on the streets – but as well as older versions, there are newer ones that have not made it yet to Europe. These newer ones generally look chunkier, with bigger locks.

Here’s a Mobike with a rather nice frame painting detail, an unusually chunky looking lock, and solar panels in the front basket:

Here’s an Ofo with a very chunky appearance, particularly the tires, which look like they could withstand anything. They are solid, but with lots of holes drilled through the rubber to presumably reduce weight and possibly generate a warning whistle (not really):

Notice also the SGBike and Mobike parked neatly beside by other users. Off the pavement, off the road, not knocked down. London, you have a lot to learn.

I did get the feeling that bikeshare might be a spent force in at least the central part of Singapore (I did not visit the suburbs) and eScooters may already have taken their place here. Coupled with Singapore not being a particularly cycling friendly city – certainly compared to London – I wonder if the only thing remaining is for the city council to sweep up the unused bikes for the bust operators, and tell the others ones it’s time to move on? I understand that the council has recently tightened up the regulations for bikeshare in the city, making it harder for the companies to operate, but a necessity in a city with the layout and streetscape like Singapore’s.