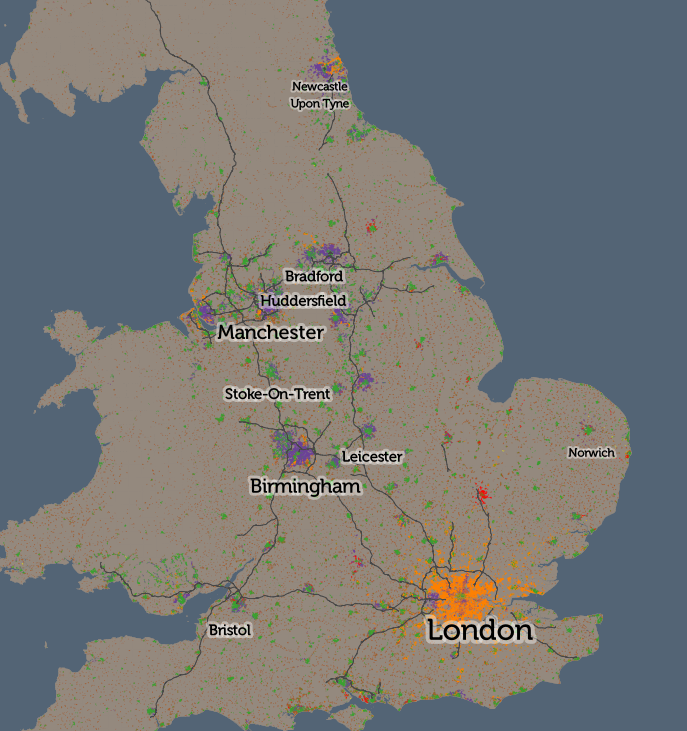

Here’s a map of the top method of travel to work, for each “small area” (~250 people) in the UK, for people aged 16-74 and in employment, at the time of the 2011 Census (or try the interactive, zoomable version):

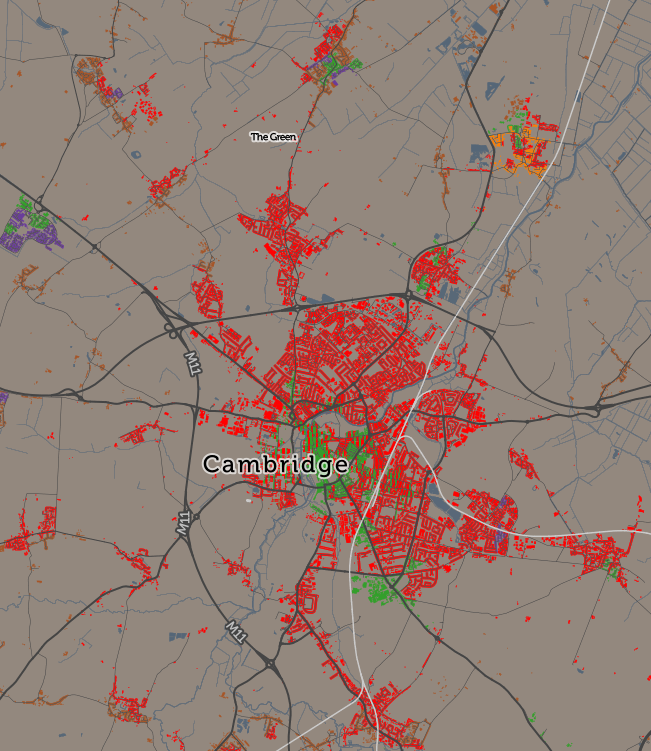

The pattern is, fairly evenly, that car use (light blue) dominates except for people living in the very centre of cities, where walking to work (green) is the most popular method. The two big exceptions are London, where rail/metro travel (orange) dominates for the inner city zone, separating the walking core and car-driving outer London ring; and Cambridge, where the cyclists (red) really are king. There are some other interesting results in small areas (e.g. walking is popular in central Leicester but not in the centre of Peterborough), but overall, the map doesn’t tell you much more.

So, I’ve considered what the map would look like if we removed cars from the calculations – what form of transport is used by the people that need to work but don’t own or otherwise have access to cars, either as a driver or passenger? How does the UK commute, without cars, right now – and what might a UK landscape look like without the great rush-hour traffic jam, if the alternatives, pro-rata, were adopted? A whimsical hypothesis – cars are always going to be essential for certain kinds of commutes in certain parts of the UK – but let’s see what happens anyway, as it will still tell us something about public transport provision, city walkability and maybe attitudes to working life in general.

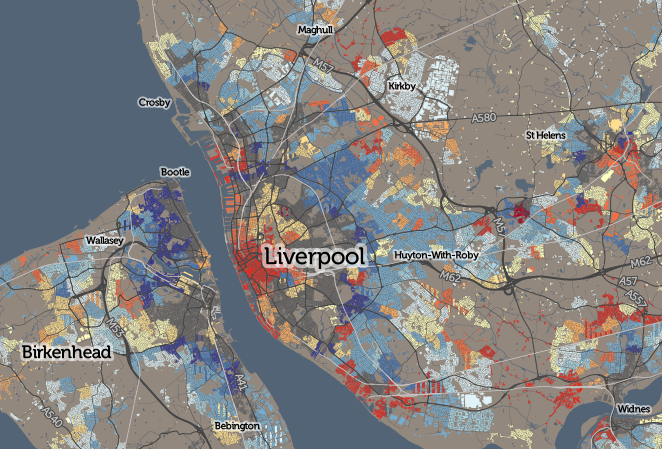

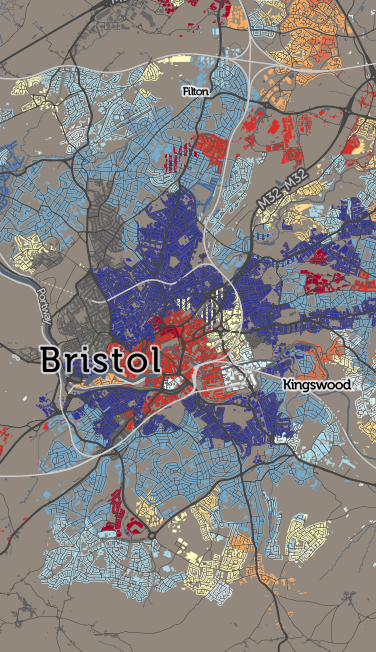

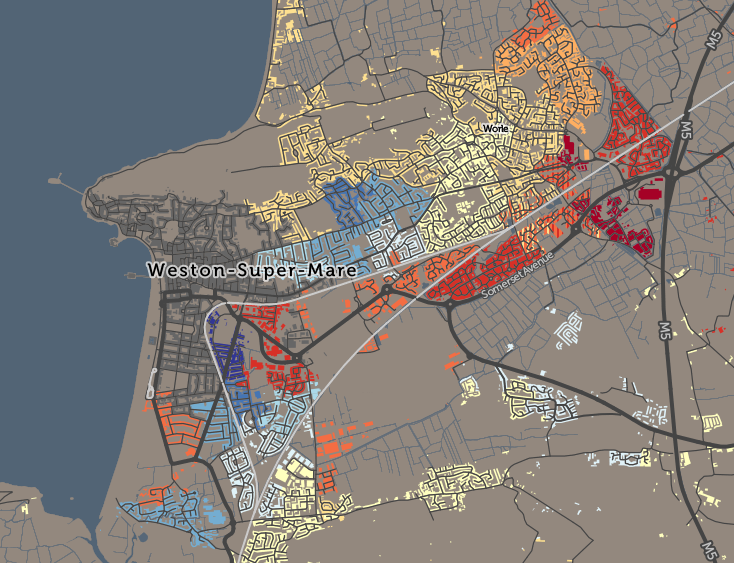

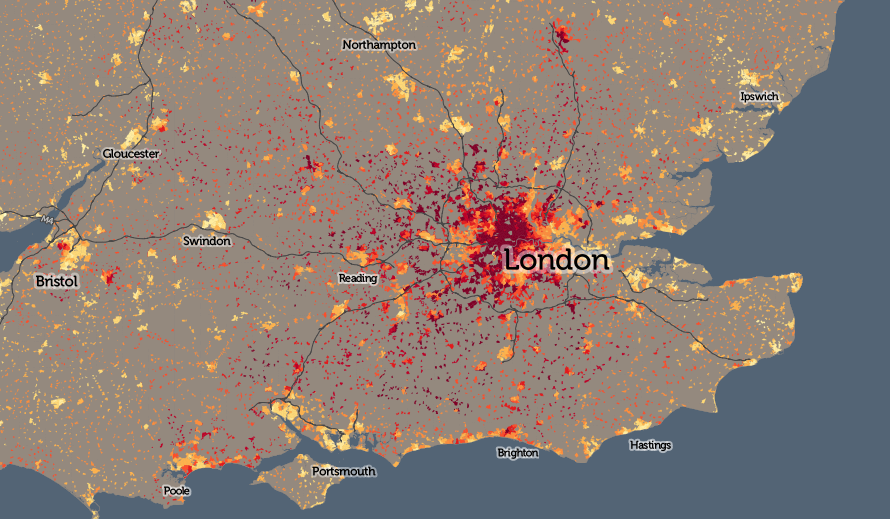

Here is a map of the top carless commute method for small areas, right across Britain:

(Here is the interactive, zoomable version).

Suddenly, all sorts of interesting trends emerge. In rural areas, working from home dominates – with no public transport, and motorbikes being an uncommon form of transport in the UK, this is the only option. In towns and villages, and in city centres, walking to work dominations. Both are obvious – the interesting results appear if you zoom in:

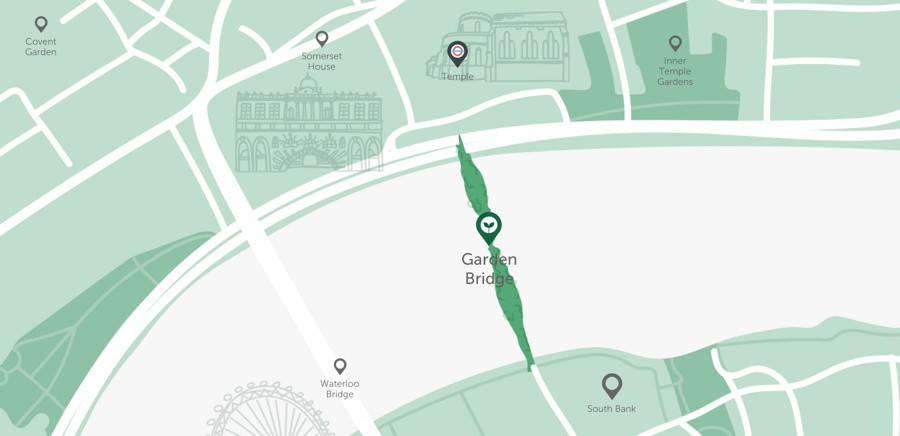

- In London, the central walking-to-work area (green) coincides almost perfectly with the congestion charge zone. Other walking areas include the large outer London town centres of Hillingdon, Croydon and Kingston that have been absorbed into the metropolis, and the traditional community of Stamford Hill.

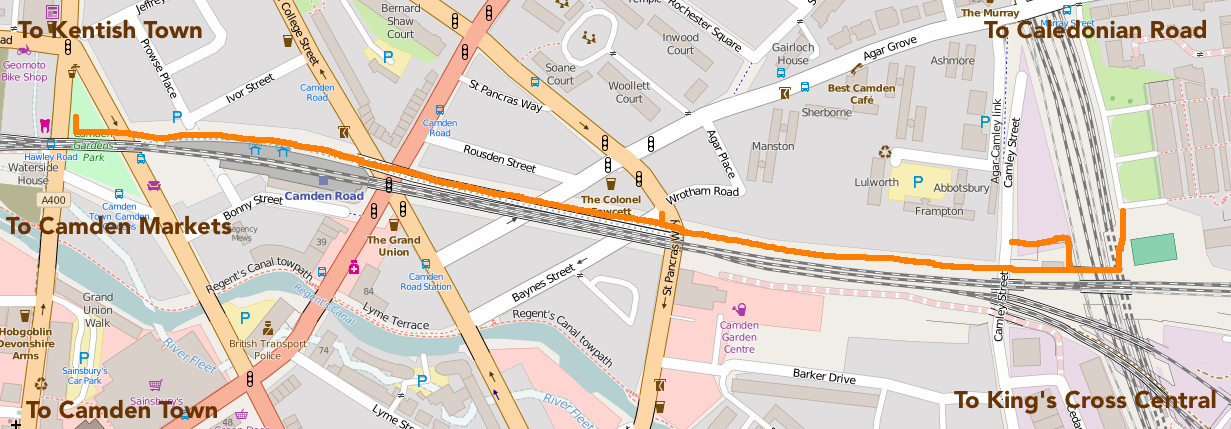

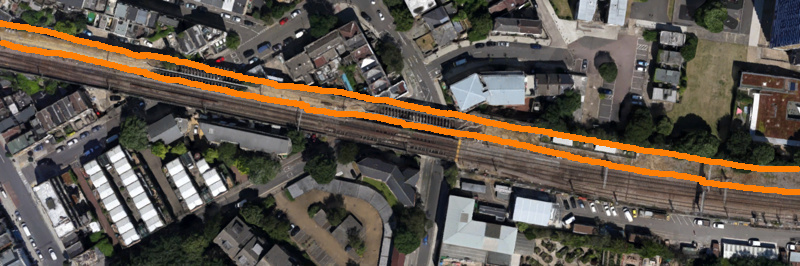

- Rail/metro (orange) dominates throughout Zones 2-6 London and beyond.

- London has four major areas of bus dominance (purple) – Burgess Park in the south, Hackney in the north-east, the western Lea Valley in the north and a huge zone surrounding Heathrow Airport in the west. Three of these not surprisingly coincide with areas of poor rail/metro provision, but the western Lea Valley result is interesting – there are two rail lines down through this area with stopping services. However, notably, this area’s most popular employment type is cleaning – cleaners typically have to work nights, where the bus is the only public transport option.

- York versus Leeds – both have a similarly sized walking core, but then the rest of Leeds has bus users, while York’s outskirts are dominated by cyclists (red). The flatter nature of York is likely the major reason.

- Buses are pretty crucial in the Birmingham conurbation.

- Cycling dominates in almost every part of Cambridge but less so in the other famous cycling city, Oxford. In London, Hackney’s famed cycle community actually has roughly equal prominence with both bus and train/metro use.

- Stoke-on-Trent has a very large walking core, larger than for the larger cities, covering the whole area almost, rather than being surrounded by bus/cycling/train commuters as normally happens. Stoke-on-Trent is actually a conurbation of six towns, with employment scattered throughout rather than concentrated in the normal core. Alternatively this could be due to poor bus provision or a dominance of driving.

- Ilkley and Bingley like their trains – nearby Keighley and Skipton, nearby and on the same network, don’t. The former two towns perhaps act more as commuter towns for Leeds while the latter two have a tradition of more local employment.

- The very richest areas have a high proportion of people working at home (brown) – live in help, aka domestic servants? See Knightsbridge and Hampstead Garden Suburb in London, or Sutton Park near Birmingham, are two examples.

- The new towns in central Scotland seems to have a greater proportion of working-at-home than equivalent new-town areas in England.

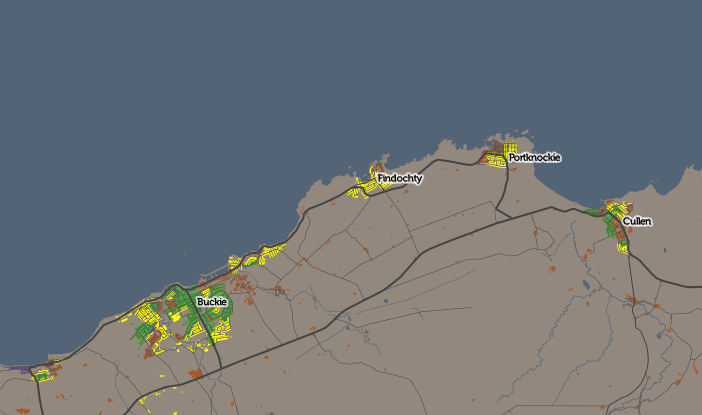

- Fishing communities (yellow – other) are obvious in north-east Scotland:

These are just a few of the spatial patterns I’ve spotted – there are I’m sure many more interesting ones. Sometimes, removing the dominant factor reveals the interesting map.

The technique of mapping only the most dominant mode of transport has a serious flaw, in that, depending on how you merge or split other transport modes, you can significantly influence which appears “top”. I have merged some modes together (driver+car passenger, train+metro+tram, and taxi+motorbike+other, e.g. boat), hopefully in a meaningful way that shows interesting results without hiding the bigger picture. Another mitigating factor is that, where a second mode of transport has nearly as much use as the first, I include its colour too, in narrow vertical banding, and highlight this in the interactive “area information” panel.

All the maps in this article use the CDRC Maps platform, created by the Consumer Data Research Centre, to map small-area consumer and other demographic data for the UK. Because I am using Census data, I am able to map for the whole of the UK (including Scotland and Northern Ireland), as, for the Census at least, the activity is coordinated across the nations, and while the outputs are arranged differently, they are sufficiently similar to combine and use together with care. The data comes from the National Statistics agencies – the ONS, NRS and NISRA, and is Crown Copyright, licensed under the Open Government Licence.

Have a look at some other CDRC datasets mapped, download the data yourself or find out more about the CDRC.

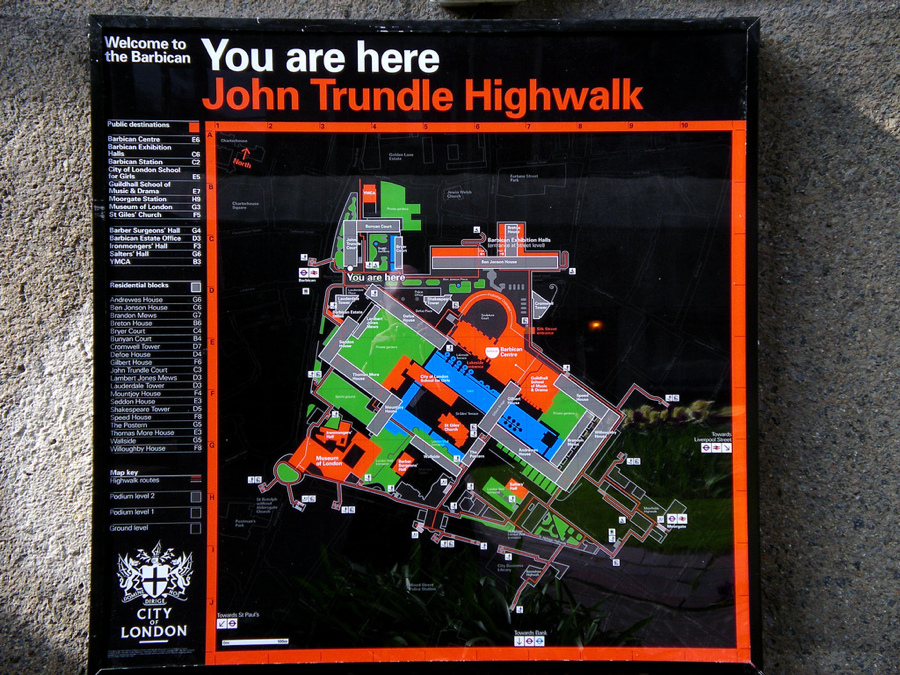

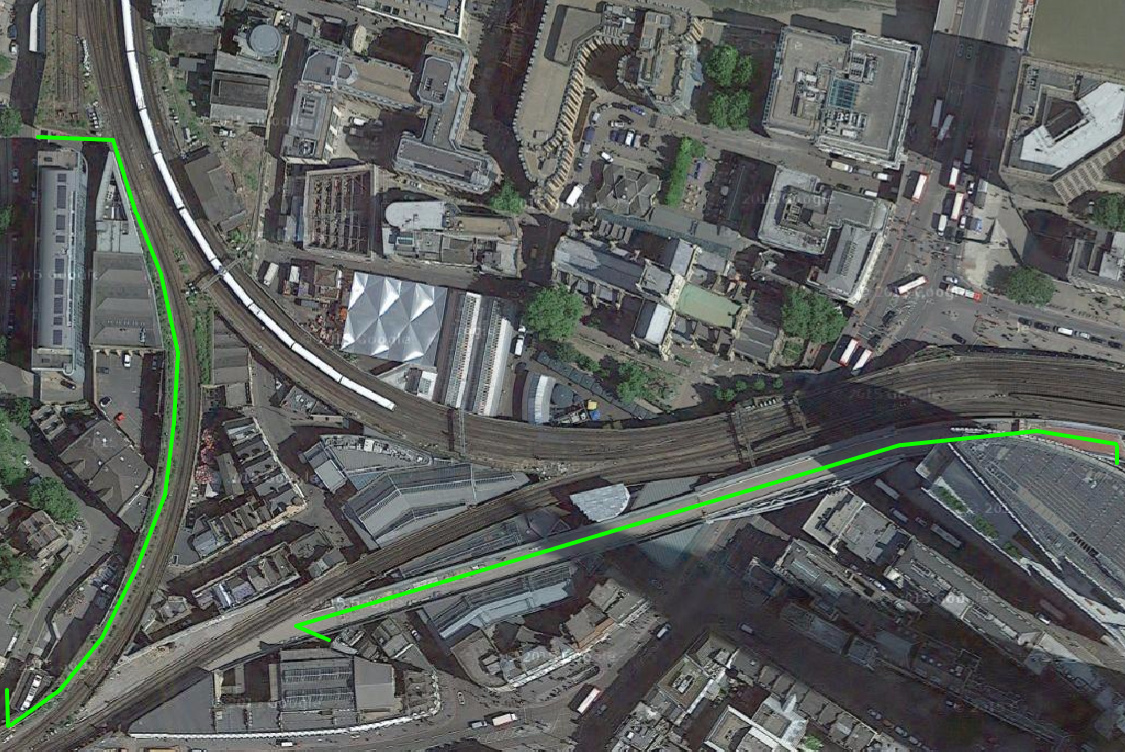

The first is the link that runs behind Tower 42 (the former Natwest Tower). It used to head east to what is now the Gherkin, however the bridge here (across Bishopsgate) was severed when the Pinnacle construction started. The Pinnacle project was then cancelled and the concrete stump is now disappearing again, to be replaced by another skyscraper – but with no bridge link restored. The other link heads north, right through the Lloyds Banking Group building, before coming to another bridge across a busy road. This is still there – for now – but leads to a dead-end, as its steps down were recently removed. So, the urban explorer here has to take the steps down just before the road.

The first is the link that runs behind Tower 42 (the former Natwest Tower). It used to head east to what is now the Gherkin, however the bridge here (across Bishopsgate) was severed when the Pinnacle construction started. The Pinnacle project was then cancelled and the concrete stump is now disappearing again, to be replaced by another skyscraper – but with no bridge link restored. The other link heads north, right through the Lloyds Banking Group building, before coming to another bridge across a busy road. This is still there – for now – but leads to a dead-end, as its steps down were recently removed. So, the urban explorer here has to take the steps down just before the road.