1. Tube trains do run to a strict timetable, rather than just “saturating” the tunnels with trains, as can appear to be the case on many lines during the rush hour.

This is not normally useful because the gap between trains is so small, so TfL doesn’t publish the timetables, except for first/last trains and, for train geeks, the Working Timetables are hidden away on their website. However, the timetables (which are accurate to quarter-minutes) are useful near the start or end of the day – particularly around midnight, where the frequencies drop right down. Journey Planners, such as Google Maps, make use of the hidden timetables. Case in point – a recent journey suggested a Circle Line train arriving at 0002 at Paddington, going eastwards. Sure enough, as I ran down the stairs a hundred seconds after midnight, it was just pulling in. For less frequent services, such as Metropolitan Line trains to Amersham, the timetables become event more important. Crossrail will also likely be relatively infrequent, especially for services to the far ends.

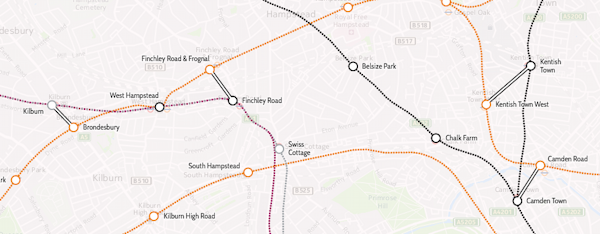

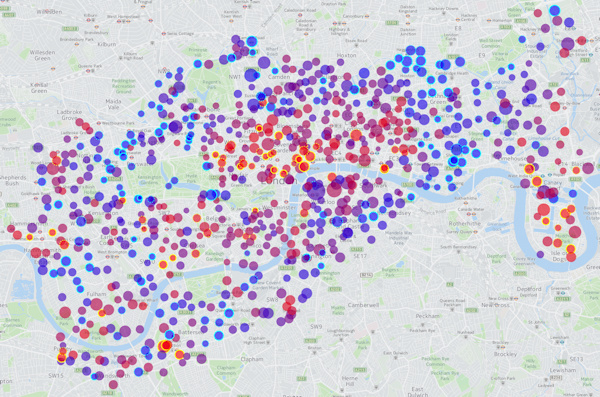

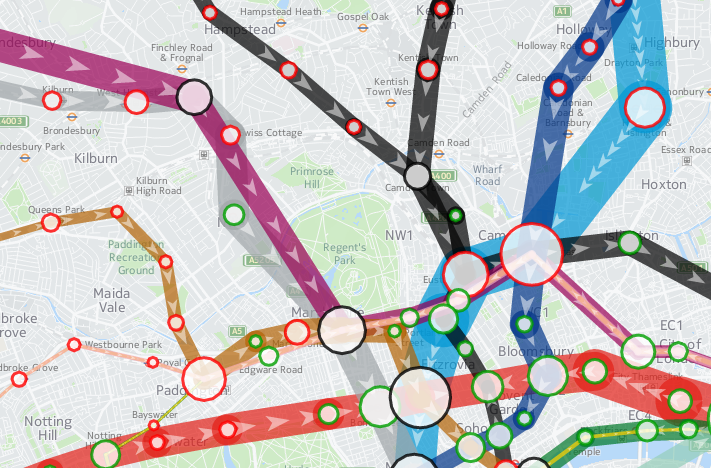

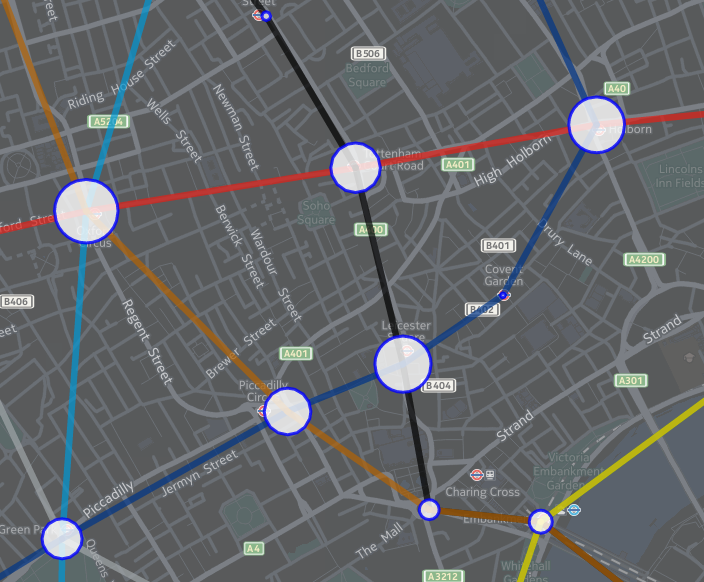

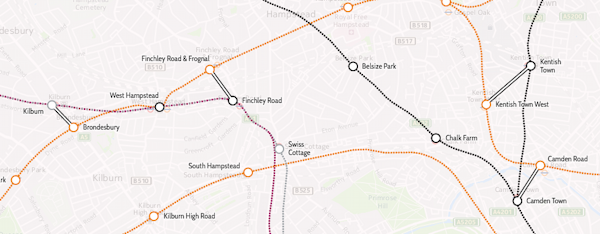

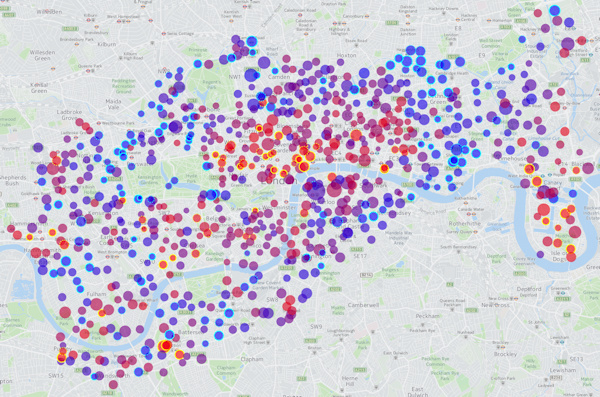

2. Out of Station Interchanges (OSIs) can be useful for saving money (i.e. avoiding Zone 1) or time (as distances can be much smaller between other lines than the tube map can suggest). They are “free” transfers which are not shown on the tube map, but which count as only one journey, even if you go out through ticket barriers and back in at the other station. The system does the maths so you don’t end up paying for too. Each OSI has a time limit between the two sets of barriers, so don’t go shopping in between the stations! You can see the current OSIs between tube/DLR/Overground stations on this map, or see this page for the complete list.

3. You don’t have to flag down, hail or otherwise signal TfL buses. This has been the case for a few years. Bus drivers will always stop if they see you at the stop and you show a vague interest towards the bus – such as facing it and looking at it. Save your weary arms and don’t give passing cyclists frights!

4. The Santander Cycles (a.k.a Boris Bikes, or generically, the London Bicycle Sharing System bikes) stretch across a wide area of central London. They charge £2 for every 30 minutes after the first half hour. You can save money on a long journey by docking just before the 30 minutes is up, waiting at least 5 minutes, and then starting the next leg of the journey, either from the same docking station or a nearby one. (N.B. Santander Bikes are not included in the Oyster/Contactless/travelcard system – yet. They may be included from summer 2017 onwards.)

5. Oyster/Contactless is always cheaper than paper tickets when travelling in Zone 1-6, or on any TfL services outside of these zones, but not necessarily when on non-TfL services travelling outside of Zone 1-6. For example, paper tickets from Gatwick Airport to London Bridge/Blackfriars or to London Victoria can sometimes be cheaper than Oyster/Contactless – particularly at weekends with “Super Off-Peak” paper tickets and especially if you have a railcard that you can’t use with Oyster/Contactless. I can travel from Gatwick to Blackfriars for £5 on Sundays with a buy-on-the-day paper ticket and a Network Railcard, but it’s £8+ with Oyster. N.B. In rare cases, the end-of-day batch calculation that Contactless uses, compared to Oyster with its immediate charging, means that Contactless can work out cheaper than Oyster. Geoff Marshall (Londonist) investigated this.

6. 2-for-1 to top London Attractions: If you have a paper train ticket (i.e. for National Rail and London Overground, not the tube) to the stations nearest the attraction then you can get a 2-for-1 on entry (e.g. Richmond to Kew Gardens for visiting the aforementioned gardens is £3 for 2 people – save £16+ on getting in). You don’t actually have to do the journey though, and you don’t need to buy the tickets from the start of your theoretical journey – buy it at the station nearest the attraction if there’s a ticket office there. Buy a journey which is very short, as then it will be cheap!

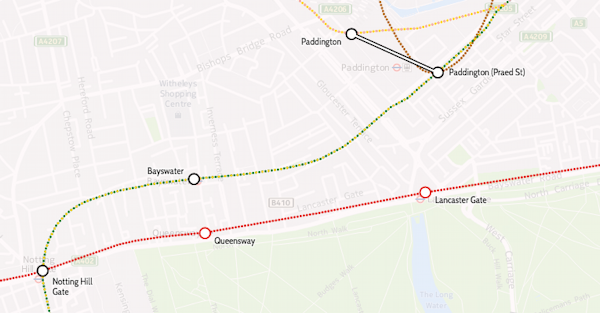

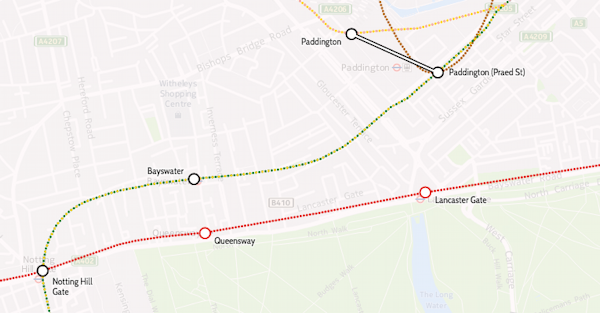

7. The tube map is far from geographical. Here are some journeys that are shorter by walking, than by taking the tube:

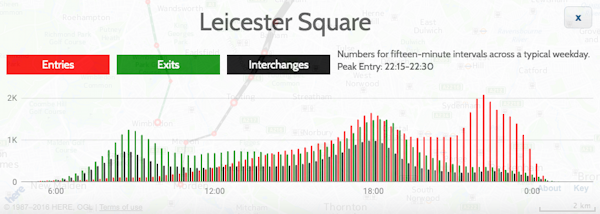

- Leicester Square to Covent Garden (450 people a day do this journey by tube! Don’t!)

- Bayswater to Queensway

- Paddington to Lancaster Gate (i.e. Hyde Park)

- Farringdon to St Paul’s

8. Sometimes, you don’t need to get the tube. A day bus pass is £4.50, but you get a free one automatically put on your Oyster/Contactless after 3 bus journeys that day, and then you can go on unlimited other TfL buses for free until 0430 the following morning. A “Hopper” ticket giving you two journeys in an hour for £1.50, is coming in September. In both cases, you pay for the electronic ticket through Oyster or a contactless credit/debit card – buses don’t take paper tickets.

9. Buses don’t have zones, but are included in any travelcard. So you can have a Zone 1-2 travelcard and then travel out from Zone 2 on a bus, to Zone 3 or right to the edge of London etc, then back into Zone 2 from Zone 3 on a bus, all on the travelcard.

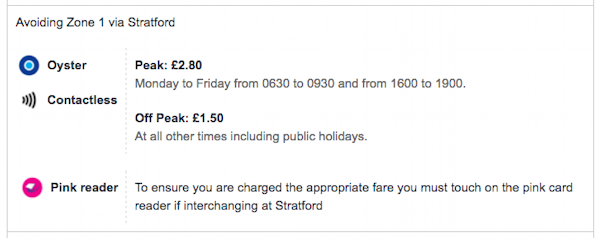

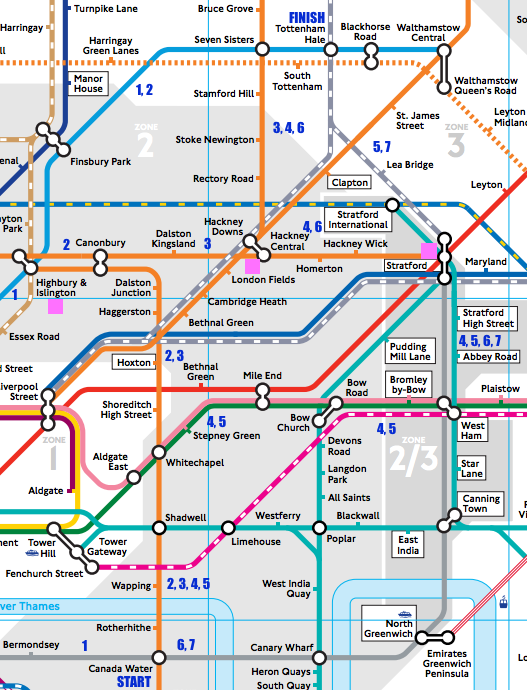

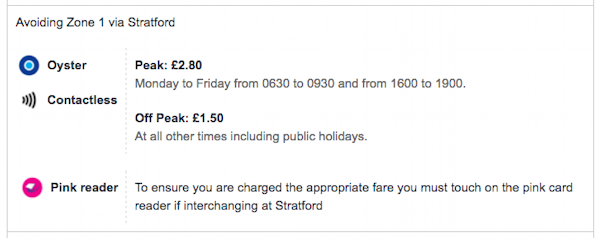

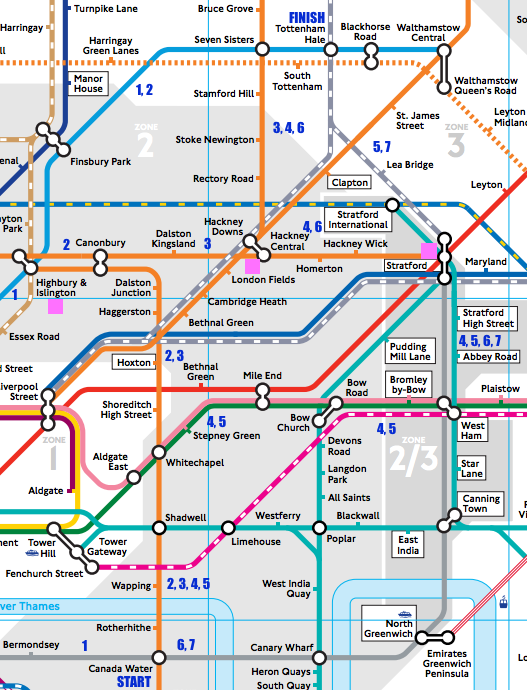

10. If you avoid Zone 1, long journeys can be extremely cheap. For example, stay on TfL rail services (Underground, Overground, TfL Rail, Tramlink) and it’s just £1.50 off-peak, no matter how far you go – you’ll need to touch on pink Oyster card readers when changing trains, to prove you went that way. Uxbridge to Upminster is just £1.50 off-peak with Oyster/contactless, despite being over 31 miles as the crow flies. Just touch the pink reader at Stratford’s Overground platforms. This doesn’t always work – if you have to travel back on yourself then you may not get the discount. For example, Earl’s Court to Highbury and Islington doesn’t work (despite both being in Zone 2), but very close by West Brompton to Highbury and Islington does, because you leave the same direction as you arrive, when changing at West Brompton. The single fare finder is extremely useful as it will always tell you if there’s an avoid Zone 1 option for your journey, and where you may need to touch a pink reader to prove it.

To complicate things even more, there’s certain journeys where touching a pink reader, will *increase* the fare you made – even if you didn’t go into Zone 1. A pink reader acts as proof you were at that place, and TfL will apply rules about logical/sensible journeys, based on this information. For example: Canada Water to Tottenham Hale: Single Fare finder says it’s £1.50 if you end at the National Rail gates there, and £2.80 if you end at the Underground gates.

There are, I think, seven sensible off-peak routes, based on Zone 1/not Zone 1 choice, whether you have a bike and that the Stratford-to-Tottenham line being very infrequent – below, I’ve assumed leaving Canada Water as soon as possible after 8pm on a normal Friday and got the times from TfL’s Journey Planner or Google Maps:

| Route |

Change At |

Zone 1? |

Bikes allowed? |

Pink Readers |

How Long (mins)? |

Fare |

| 1 |

Green Park |

Yes |

No |

– |

33 |

£2.80 |

| 2 |

Highbury & Islington |

Yes |

No |

– |

33 |

£2.80 |

| 3 |

Canonbury, Hackney Central |

Yes |

Yes |

– |

45 |

£1.50 |

| 3 |

Canonbury, Hackney Central |

Yes |

Yes |

Hackney Central |

45 |

£2.80 |

| 4 |

Whitechapel, West Ham, Stratford, Hackney Central |

No |

Yes |

– |

|

£1.50 |

| 4 |

Whitechapel, West Ham, Stratford, Hackney Central |

No |

Yes |

Hackney Central |

|

£2.80 |

| 4 |

Whitechapel, West Ham, Stratford, Hackney Central |

No |

Yes |

Stratford |

|

£1.50 |

| 4 |

Whitechapel, West Ham, Stratford, Hackney Central |

No |

Yes |

Stratford, Hackney Central |

|

£1.50 |

| 5 |

Whitechapel, West Ham, Stratford |

No |

Yes |

– |

|

£1.50 |

| 6 |

Stratford, Hackney Central |

No |

No |

– |

|

£1.50 |

| 7 |

Stratford |

No |

No |

– |

34 |

£1.50 |

Cheaper than it should be, Pink validator increases your fare, more expensive than it should be, Pink validator increases your fare, correctly

There are other possible routes, but they are less sensible (i.e. not as fast), such as taking the Overground circle the long way around (via Clapham Junction).

If you go via Canonbury and Hackney Central/Downs (route 3), you pass through Zone 1 (Shoreditch High Street station), however the default off-peak fare is £1.50 as you finish at the National Rail gates. Touching at the interchange between Hackney Central and Hackney Downs will increase the fare to £2.80, because you proved you’ve gone that way, not via another route changing at Stratford only, which does avoid Zone 1. You could go in fact still change at Stratford and Hackney Downs/Central, which avoids Zone 1, but touching at Hackney Downs/Central will charge you the Zone 1 fare. This route is sensible, because the direct Stratford trains are only once every 30 minutes (and often not running at all). An even more convoluted route, changing at Whitechapel, West Ham, Stratford and Hackney Downs/Central, is still viable for me, as if I’m taking a bike on the train, I can’t do the Mile End to Stratford or Canada Water to Canning Town sections…

You made it! The building beams cast a reflection on the glass panels which is surprisingly strong but an hour before sunset they turn off the inside lighting, which helps, and after dark it is not a problem. There are also free (yay!) digital telescopes arranged around the edge (press the button on the left to get the live view, which unfortunately does not zoom in as far as the historic image views – take your own binoculars or telephoto lens, if you are trying to spot your suburban home!) The photo at the bottom of this post is the first view you see – looking to the south. It’s the least exciting direction, but is still visually striking. N.B. In this photo, on the top of the building at the bottom, which is itself a 25-floor skyscraper (Guys Hospital), you can spot Wally on the roof. He is there for a few more days, as part of an aerial I-spy.

You made it! The building beams cast a reflection on the glass panels which is surprisingly strong but an hour before sunset they turn off the inside lighting, which helps, and after dark it is not a problem. There are also free (yay!) digital telescopes arranged around the edge (press the button on the left to get the live view, which unfortunately does not zoom in as far as the historic image views – take your own binoculars or telephoto lens, if you are trying to spot your suburban home!) The photo at the bottom of this post is the first view you see – looking to the south. It’s the least exciting direction, but is still visually striking. N.B. In this photo, on the top of the building at the bottom, which is itself a 25-floor skyscraper (Guys Hospital), you can spot Wally on the roof. He is there for a few more days, as part of an aerial I-spy.